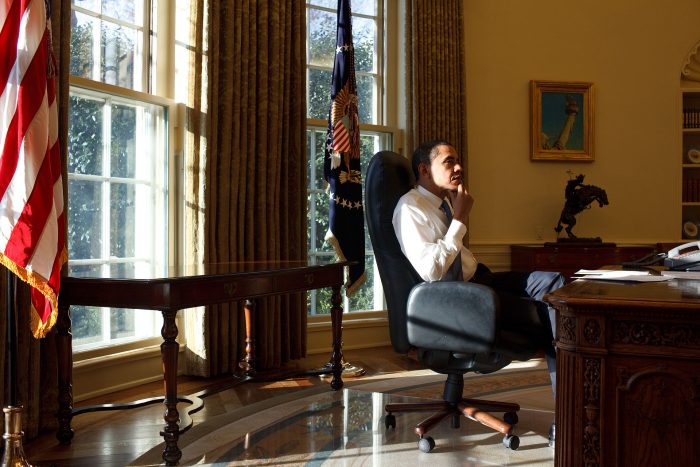

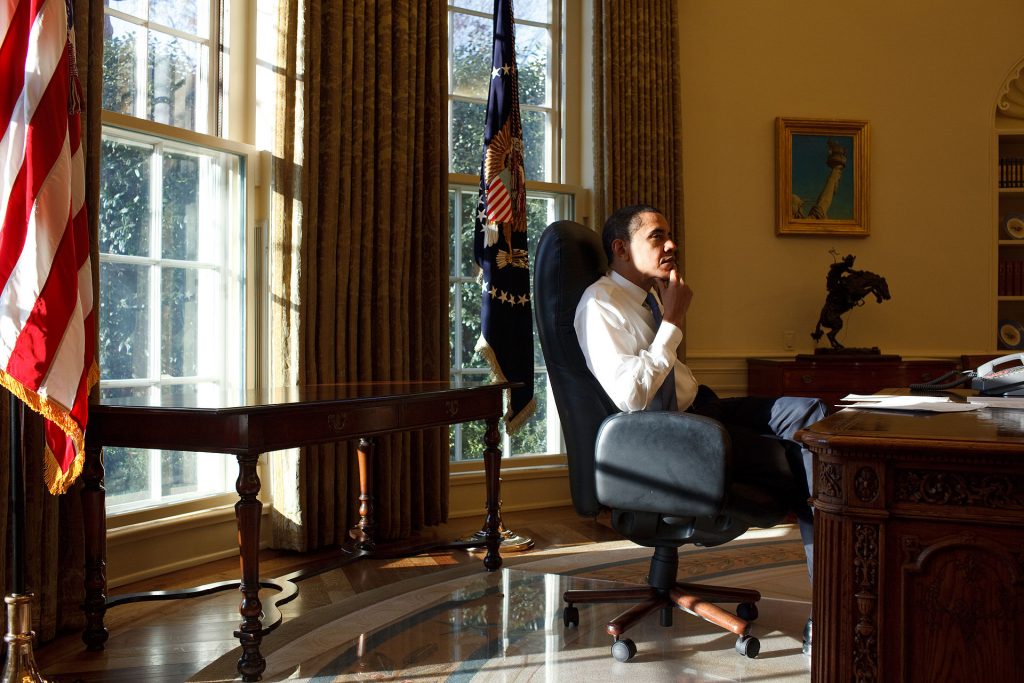

As long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible. . . . But it is a story that has seared into my genetic makeup the idea that this nation is more than the sum of its parts—that out of many, we are truly one. ~Barack Obama

Barack Obama here expresses one of the most enduring ideas about the United States: America as a land of opportunity, where anybody (well, so far any man) can aspire to be president. The National Park Service, National Archives, state and local governments, and private nonprofit organizations operate at least eighty-seven places commemorating forty-four past presidents. The list includes Mount Vernon, the homes of John and John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, James Madison’s Montpelier, and most recently the Bill Clinton Birthplace and the George W. Bush Childhood Home (also the home of George H. W. Bush between 1951 and 1955). There are also presidential libraries, tombs (Monroe, Grant, and McKinley), and monuments in Washington, D.C. (Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and both Franklin Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt).

Memorializing Presidents

Why do we memorialize presidents? One answer is that presidents themselves consciously worked to secure their legacies as patriotic and revered leaders. George Washington, for example, sat for twenty-four portraits during his lifetime, and modern presidents—beginning with Franklin Roosevelt—have had a hand in creating their presidential libraries.

Many of us memorialize presidents because we have been taught—and we believe—that the presidents literally personify the nation. From the start, when the nation was a fragile union of thirteen contentious former colonies, writers, artists, and educators tried to bind the country together by portraying George Washington as the human face of the abstract principles on which the nation was founded. Never was this more evident than when The Apotheosis of Washington was painted in the oculus of the Capitol Dome in 1863. As the divided nation tore itself apart during the Civil War, the deified first president looked down from the heavens beneath a banner declaring E Pluribus Unum.

It is for good reason that Washington became known to succeeding generations as “the father of his country.” He was unanimously elected president in an age of hereditary kings whose subjects believed him to be the embodiment of the nation-state. Washington instilled in the office of the presidency republican values that rejected European traditions of inherited rule, but the belief that the president personifies the nation nevertheless crossed the ocean and lives on to this day.

Indeed, the idea that the presidency is synonymous with the nation makes patriotic nationalism a central component of America’s traditional narrative. Even though there was no direct connection between FDR’s presidency and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, for example, visitation spiked at his presidential library immediately afterward—likely because Americans were seeking a meaningful way to express and reinforce their patriotism.

To many Americans and many historians, however, the history of the presidency is full of examples that contradict the traditional celebratory and patriotic narrative. Three Founders who became president, for example, held other human beings in bondage even as they declared that “all men are created equal.” Beginning with Jefferson, presidents tried to remove Native Americans from their lands—Andrew Jackson, in the name of national security, even pursued policies that were arguably genocidal. Abraham Lincoln chose saving the Union over freeing the slaves until half-way through the Civil War. And he, like James Monroe, advocated resettling freed slaves in Africa rather than allowing them to share the “blessings of liberty” in the country of their birth. Seventeen men would occupy the office of the presidency after women gathered at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 to promote their equality before gaining the right to vote with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Woodrow Wilson, father of the League of Nations, was also responsible for the establishment of Jim Crow policies. Franklin Roosevelt, whose New Deal brought hope, dignity, and financial security to the nation’s most forgotten men and women, is also remembered for interning nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Ronald Reagan restored popular faith in the presidency but also seriously undermined the rights of the American worker.

Relevance

Many everyday Americans have—for a variety of reasons—grown alienated from American history and come to believe that the presidency is no longer relevant to their lives. Some, driven by anti-government rhetoric in the media, may have even come to regard the nation’s history as a betrayal of the patriotic values that they learned in school. Obama’s “out of many, we are truly one” sometimes rings hollow, and too many people have grown unwilling to memorialize the presidency or visit presidential historic sites.

Lots of Americans, though, remain committed to the democratic values of the Founders and many (if not all) of the presidents. For their part, social historians have for years been exploring the experiences of immigrants, workers, racial and ethnic minorities, enslaved people, Native Americans, women, children, families, and people with disabilities or different gender identities to create a more inclusive historical narrative. And while often critical, the underlying point of this history is that by protest and/or working together Americans have generally succeeded in extending their freedoms and overcoming the forces that have divided them—whether by race, ethnicity, gender, or class. This is inclusive history and it carries a very powerful message that historians should embrace and aggressively pursue.

Engaging Audiences

Many people who visit presidential sites come to demonstrate their patriotism and often hold emotionally charged opinions about their presidents. Still, while presidential sites may occupy sacred ground, they are also educational institutions where historians can introduce the public to historical context and the many nuances of historical interpretation. Because history resonates differently with different audiences, however, historians at these sites first need to acknowledge and show respect for the diverse points of view they are likely to encounter at their museums and libraries. History professionals can learn from visitors who hail from different cultures and understand history differently than they do. At the same time that historians respectfully engage visitors in the give and take of democratic discourse, they also need to remember that they too have valuable expertise. Historical interpretation should be based on the best available evidence.

Public audiences sometimes need help moving beyond myths and legends to understand why a given president made the decisions he did. Did he marginalize certain groups out of bigotry or prejudice? Or did he believe that he needed to make a hard decision because of other circumstances? Could he have chosen a different course? Did others in positions of power make different choices? What are different historians’ perspectives on the subject? A useful rubric for an inclusive history of the presidency might pose this question: How well did a given president employ the power of his office to advance equality, civil rights, liberty, and democracy?

Addressing Controversy

Every presidential site is different, just as every presidency offers different opportunities for exploring its own narrative. Consider, for example, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum. Twenty years ago certain subjects were taboo in the museum’s permanent exhibition. Roosevelt’s response to the Holocaust was one of them, because museum leaders felt that discussion of the subject might tarnish the memory of Roosevelt’s presidency. Still, historical studies in the 1980s criticized Roosevelt for inaction or even charged him with complicity in the deaths of millions of Jews, and the museum recognized that it needed to include some representation of the Holocaust. But instead of an interpretation that placed the subject in context and presented alternative historical interpretations, the museum offered a single object: a de-consecrated manuscript scroll of the Torah that had been rescued from a Czechoslovakian synagogue in 1938. There was no interpretive label, just catalog information that the National Council of Young Israel had presented the Torah to Roosevelt on March 14, 1939, to “inspire thousands upon thousands of young people with deeper respect and reverence for the eternal values contained therein.” Displaying the Torah implied (but did not explicitly state) the message that the museum hoped to convey—that the Jews of his day admired Roosevelt and that, even though the Holocaust took place during his presidency, there was little Roosevelt could do beyond his central goal of winning the war and defeating Hitler as quickly as possible.

This institutional response to responsible criticism was good as far as it went, but it failed to acknowledge any alternative interpretations. Worse, it did not mention the fact that the overwhelming majority of Czechoslovakian Jews died in Hitler’s extermination camps; neither did it engage its audience in a conversation about the causes and legacies of the Holocaust.

The museum has since recognized the problem, and today has made a deeper story of the Holocaust an important part of its permanent exhibition. Two of ten interactive touch screen kiosks now feature digital flipbooks (titled “Confront the Issues”) that encourage visitors to explore for themselves Roosevelt’s response to the Holocaust: FDR and the Prewar Refugee Crisis and FDR and the Holocaust 1942–1945. Visitors get to examine facsimile documents and photographs and, under “Historical Perspectives,” read historians’ differing views on the subject. They consequently learn to appreciate and respect alternative—more inclusive—narratives, and they come away with their own, now more informed, interpretations.

While the interpretation of this and other controversial issues questions the traditional celebratory narrative of the Roosevelt presidency, it has not led to any outpouring of protest at the museum. Nor has it damaged Roosevelt’s reputation. Quite the opposite. Visitors instead feel more respected and appreciative of thought-provoking museum displays and texts that encourage them to better understand Roosevelt and the democracy that he and Americans of his era championed.

Civic Obligations and an Engaged Citizenry

Americans in all eras have faced challenges to their democracy. Historians have a civic obligation to help people understand the complexities of the past so that they can make better decisions in the present. After all, the idea that an educated citizenry is essential to democracy is written into our national DNA. As Jefferson wrote to Madison from Paris in 1787, “Educate and inform the whole mass of the people. . . . They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.” Washington agreed. He wrote in his Farewell Address, “In proportion as the structure of government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.”

The question we sometimes ask ourselves today is whether or not Barack Obama was a great president. Only time will tell. But the measure of Obama’s success—like that of every other president—lies not in his group identity, but in his dedication to the great principles on which the nation was founded and his mastery of the forces that shaped his presidency. Obama himself understood this. Remember his contention that “the idea that this nation is more than the sum of its parts—that out of many, we are truly one”? It suggests that Obama recognized that the success of his presidency was possible only because of the durability of the nation’s founding principles.

Historians have important work to do. Franklin Roosevelt, a keen student of history, knew this when he wrote that a “Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.” If Americans—all Americans—hope to learn from the past, they need to find better ways to learn it together. For historians, certainly, working with the public to develop a more inclusive history of the presidency is an essential way to strengthen the nation’s democracy and make it work for the diverse, multi-racial, and multi-ethnic society we are today.

Suggested Readings

Atkinson, Rick. “Why We Still Care About America’s Founders.” New York Times, May 11, 2019.

Koch, Cynthia. “The American Story: From Washington to Roosevelt, Reagan and Beyond.” The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation@Adams House, Harvard. November 10, 2015.

Koch, Cynthia. “The End of History? FDR, Trump and the Fake Past.” The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation@Adams House, Harvard. May 15, 2019.

Lepore, Jill. “A New Americanism.” Foreign Affairs.com. February 5, 2019.

Loewen, James W. Teaching What Really Happened. New York: Teachers College Press, 2010.

Moss, Walter G. “Which Presidents—If Any—Did Right by Native Americans?” History News Network. October 7, 2018.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. 1980. Reprint. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 1999.

Author

~ Cynthia M. Koch is Historian in Residence and Director of History Programming for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House, Harvard University. She was Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York (1999-2011) and subsequently Senior Adviser to the Office of Presidential Libraries, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 2013-16 she was Public Historian in Residence at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY where she taught courses in public history and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. She was a member of the Board of Directors of the National Council for Public History (2010-2013) and Executive Committee (2011-2014). Previously Dr. Koch was Associate Director of the Penn National Commission on Society, Culture and Community, a national public policy research group at the University of Pennsylvania. She served as Executive Director (1993-1997) of the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and was Director (1979-1993) of the National Historic Landmark Old Barracks Museum in Trenton, New Jersey. A native of Erie, Pennsylvania, she holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in American Civilization from the University of Pennsylvania and a B.A. in History from Pennsylvania State University.