Digital history is an approach to researching and interpreting the past that relies on computer and communication technologies to help gather, quantify, interpret, and share historical materials and narratives. It empowers individuals and organizations to be active participants in preserving and telling stories from the past, and it unlocks patterns embedded across diverse bodies of sources. Making technology an integral component of the historian’s craft opens new ways of analyzing patterns in data and offers means to visualize those patterns, thereby enriching historical research. Moreover, digital history offers multiple pathways for historians to collaborate, publish, and share their work with a wide variety of audiences. Perhaps most important, digital methods help us to access and share marginalized or silenced voices and to incorporate them into our work in ways not possible in print or the space of an exhibition gallery. This essay provides an overview of the multiple ways historians are using digital tools to research and share inclusive histories with broad audiences.

The Growth of Digital History

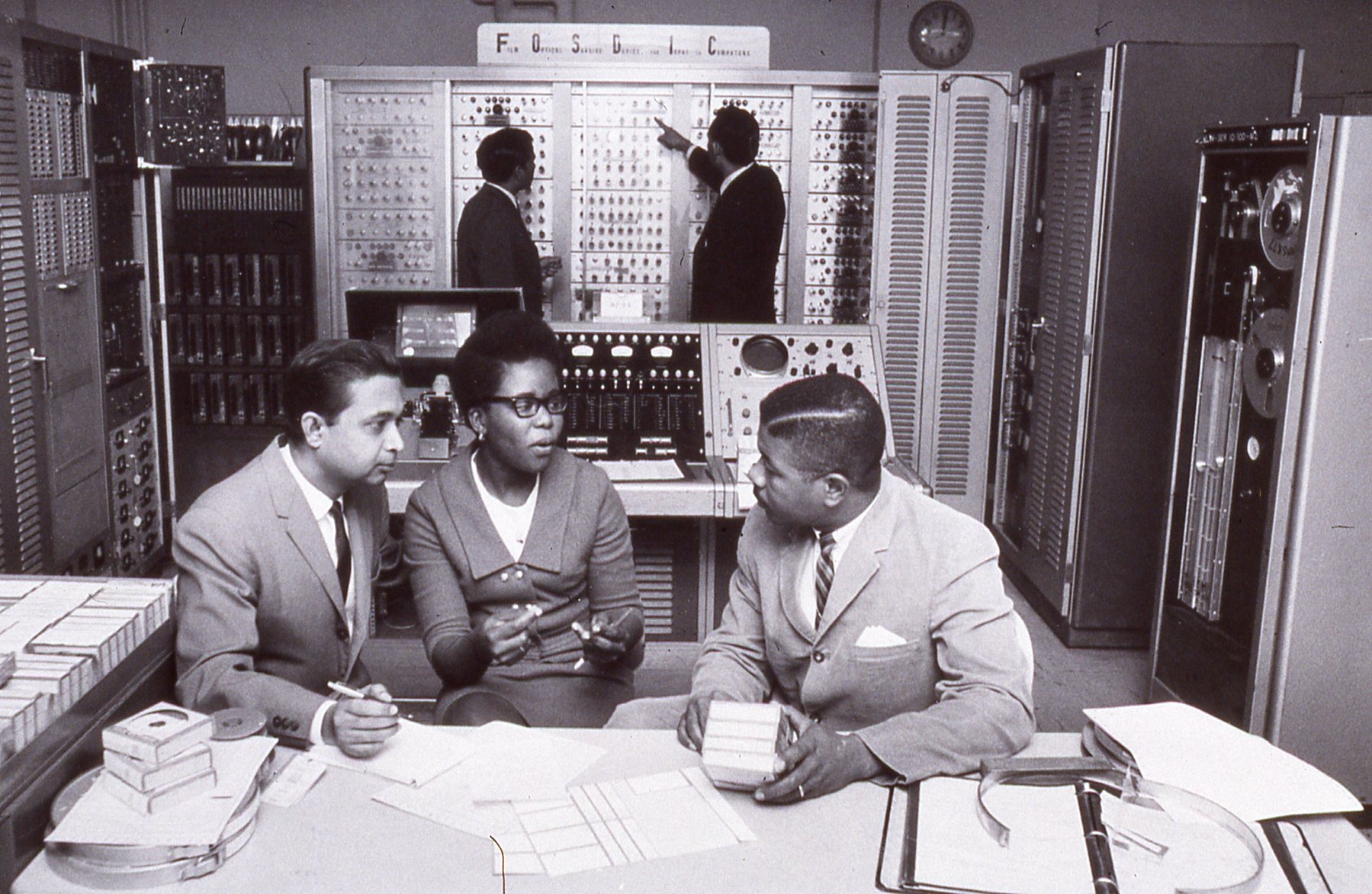

Over the last twenty-five years, digital history has grown into a subfield of its own. Using computers to assist in both historical analysis and the sharing of historical narratives is not new. Economic and social historians began adopting computer-based statistical methods in the 1960s to analyze historical data as means for documenting and quantifying different communities. In the 1980s and 1990s, as personal computers became more available and accessible, some historians created simple databases of sources, transcriptions, and numerical data derived from their own research. The birth of the Web and the first modern browser, Mosaic, in 1993, opened new means for sharing, networking, and collaborating in ways not previously possible. Using computer languages designed for the Web, historians found opportunities for crafting and publishing narratives filled with links to other resources, creating non-linear pathways that encouraged new ways of reading.

An important milestone occurred in the 1990s when cultural heritage institutions began creating digital copies of their holdings and sharing them online for free. The Library of Congress’s American Memory and the New York Public Library’s first iteration of the Digital Schomburg collection were path-breaking resources that facilitated access to sources for historians and students. Genealogists, collectors, and enthusiasts benefited from these collections, and the Web provided a means for them to share their passion and connect with others. Genealogists, in particular, benefited from digitized databases of passenger records from the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation records documenting immigrants entering Ellis Island. In this period, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints also began its long history of providing access to digitized U.S. Census records and other public records.[i] Collector Omar Khan launched a website filled with his collections, Harappa: The Indus Valley and the Raj in India and Pakistan, driven by his personal interest in the histories of South Asia. Soon after the site launched in 1995, Khan connected with scholars in and of the region and the Harappa grew beyond a hobbyist’s project into an impressive online resource containing collections and exhibitions on two distinct eras in South Asian history.[ii] Motivated by the potential to expose and document voices from underserved and under-heard communities, individuals and organizations gravitated to the Web to harness the power of computers to collect, analyze, and present digitized data.

Digital Collections

Today, digitized collections of primary sources from thousands of libraries, archives, and museums continue to facilitate access to existing collections. Many of these collections replicate existing archival structures and collections. As such, digital collections can reproduce the power structures, and absences, involved in the creation of the original physical archives. At the same time, digital scanning and photography, combined with web protocols, have allowed individuals and organizations to build, curate, and share more inclusive collections around themes and communities. Online collaborative research collections, such as the Digital Library of the Caribbean, combine resources from multiple organizations to serve an international and multi-lingual audience and promote the study of Caribbean history and culture. Since their founding in 2004, their governance model is designed with principles of equity and inclusion: decision-making is shared and the combined monetary and professional resources are distributed equitably across more than forty institutions.[iii] When designated physical spaces for certain types of archival material do not exist (or are limited), people are creating digital spaces to fill the gap.

An important example of digital collections work documenting under-heard voices is the Colored Conventions Project. Led by Gabrielle Foreman and a large collaborative team at the University of Delaware, it brings together newly-digitized sources related to Black political conventions from the 1830s to 1890s into a website that includes minutes from local, regional, state, and national meetings discoverable by year, place, and subject tags. To make the scanned documents fully text searchable, Foreman and her team collaborate with students and community groups, including African American churches, to transcribe documents and research the lives of individuals mentioned in meeting minutes, most of whom are not national figures. Through this community-sourced research, a new story of African American political activism is emerging.[iv]

Many digital collections projects begin outside of academic institutions. The South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), led by Michelle Caswell and Samip Mallick, began as a way for the organizers to see themselves and their community in history. After ten years of collecting digitally, it holds thousands of items making it the largest collection of South Asian American history.[v] When the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) first formed, they lacked a physical collection and turned to digital means to jumpstart their efforts. The museum launched an online Memory Book in 2007 that asked visitors to share their stories, family photos, or traditions. These early contributions influenced how curators shaped their interpretative priorities and helped them build their physical and digital collections. This practice also informed their digital strategy from the institution’s earliest stages.[vi] These digital collections provided building blocks for writing and teaching more inclusive histories.

Teaching and Learning

Some of the earliest digital history projects sought to bring students into direct contact with digitized primary sources and multi-media interactives to teach historical methods and analysis. History Matters offered one of the first free online U.S. history courses designed for high school and college classrooms, based on the textbook and CD-ROM, Who Built America?. By assembling different types of primary sources to represent many voices from the past and publishing guides to help students interpret different kinds of evidence, History Matters demonstrated the potential for building inclusive and synthetic teaching materials for the Web—such materials are now collectively known as Open Educational Resources (OERs).[vii] Since these early projects, educators have posted lesson plans, activities, and other materials online, which has created a need to aggregate these sources in central places for teachers, leading to sites such as EDSITEment and Teaching History.org.[viii]

Immersive websites and games have also played an important role in history education. In Who Killed William Robinson?, launched in the late 1990s, Canadian historians experimented with an immersive site that invited students to closely examine primary and secondary evidence pertaining to a specific historical event. Designed to help undergraduates understand historical methods and uncertainties in the record, the project asked students to spend time reading about the contexts surrounding the murder and associated events, then dig through a collection of primary sources and different interpretations of the events. Students using the website quickly learned how murky evidence presented at trial led to the conviction and execution of a Chemainus Indian and many questioned the verdict. Project co-creators, Ruth Sandwell and John Lutz, wove together the social, cultural, and political contexts at work in colonial British Columbia to help students solve the mystery behind the death of William Robinson and other African Americans who migrated to British Columbia in the 1860s.[ix] Designing investigative activities like Who Killed William Robinson? and other serious educational games requires an intense amount of technical and research resources to build and sustain as web browsers evolve and the use of mobile devices continues to increase.

Historians are also sharing and creating undergraduate and graduate-level syllabi online to encourage more inclusive reading lists and assignments that acknowledge and respond to current events. Responding to racially-motivated violence in the 2010s, educators began generating reading lists to promote teaching the history of racial violence, mass incarceration, and white supremacy. One example is #CharlestonSyllabus, initiated by Brandies University professor Chad Williams, following the horrific 2015 shootings at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The resulting community-sourced resource, now maintained by Keisha Blain and the African American Intellectual History Society, is filled with books and articles on relevant historical topics, many of which were written by scholars of color. These efforts encourage instructors to teach and discuss difficult historical, cultural, and political topics with their students.[x] Through these examples, we see historians building both simple and complex projects to engage students in historical thinking and research.

Digital Exhibits and Publications

Unlike a print article that has an accepted structure and form designed to be read sequentially, digital narratives offer historians the ability to create non-linear paths to explore themes and paths of argumentation and invite conversations with community audiences. Some projects invite users to see complexity in history by following different pathways through layers of content including: links to digitized primary sources; visualizations of historical data in maps, graphs, or charts; and narrative threads that work together to address historical questions in ways not possible in print monographs or exhibition catalogues.

American Sabor: Latinos in U.S. Popular Music is an example of an online exhibition that accompanied a traveling show developed by EMP Museum and the University of Washington. American Sabor’s bilingual website invites Spanish and English speakers to learn about the musical contributions of Latinx musicians and how their culture shaped the American popular music scene after World War II. Site visitors learn about Latinx migration in and out of particular regions, hear musicians’ oral histories, learn about musical styles such as the Rumba and Mambo, and listen to sample songs. This exhibition brings together multiple kinds of sources—including sound—that are important for telling more inclusive histories by using digital means to craft historical arguments about the past.

Digital publishing platforms such as Scalar, Omeka, WordPress, and Manifold offer historians the means to bring together annotated media and sources with long-form writing and embed visualizations not possible in a book. In one example, Matthew F. Delmont has created an online companion to augment his print monograph, Why Busing Failed. The digital edition is a free and accessible version of his research that incorporates in-depth examination of multimedia sources and provides him the opportunity to reframe his academically-focused monograph as more approachable online essays that offer twelve new ways to rethink the way that the history of school desegregation and civil rights is taught in American schools.[xi]

Professional organizations are also turning to free digital publishing platforms as ways to reach and support their members by discussing new scholarship, but also to provide a voice for their organizations’ advocacy roles in the profession and public policy, as well as in struggles for social justice. The African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) publication Black Perspectives, an award-winning digital history site with dozens of contributing scholars, promotes and disseminates “scholarship on global black thought, history, and culture.” The National Council on Public History and the American Association for State and Local History decided to publish The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook online as a free resource not only for their members, but also to open the practice of history for diverse communities of practitioners and directly support inclusive and equity-focused historical work in public settings.[xii] Free online publishing software facilitates a type of dialogue that many inclusive historians already engage with in other ways; however, it expands the reach, depth, and breadth of these conversations.

Collaborative Digital Public History

Digital public history practitioners collaborate with groups outside of the academy and other formal cultural institutions to document their experiences and work together in telling their histories. For example, Outhistory.org launched in 2008 by a team led by Ned Katz to facilitate collaboratively-written histories of the LGBTQ community. The project collects personal reflections, but it focuses on using its Wiki publishing platform as the means to collaboratively write and discuss episodes important to the diverse LBGTQ community. As the number of contributors grew, so did the project’s stature as a resource for LGBTQ history.[xiii] Public historians are also actively trying to change understandings of American history and the shared racist, colonial, and exclusionary legacies that are made visible through current events. Denise Meringolo created Preserve the Baltimore Uprising to document the events of protest by those living and experiencing it in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray in 2015. The project began as a crowdsourced, community collecting project, but it continues to transform as Meringolo works with Baltimore residents, including high school students, to reflect and interpret this series of events within the historical roots of racial injustice and political unrest in their city.[xiv]

In reaction to racially-motivated police violence in 2014, museum professionals Aleia Brown and Adrianne Russell, started the hashtag #museumsrespondtoferguson to begin a long conversation about how museums and cultural heritage organizations might improve and change racial and cultural understandings within their communities. By hosting regular conversations on Twitter and blogging, Brown and Russell encouraged museum professionals to examine their hiring practices, collections policies, and public programming offerings.[xv] By using social media platforms like Twitter with hashtags that can be followed in-real time and asynchronously, robust conversations occurred in ways that are not possible within the confines of conference presentations or other in-person meetings. There are risks, however, when public historians participate in community conversations of highly-contested historical episodes, such as the building of Confederate monuments in the early twentieth century. In the absence of skilled facilitation, it can sometimes be difficult to participate in thoughtful and rational discussions and it is easy for discussants to be dismissive, rude, and even threatening. People of color, LGBTQ individuals, and women are more often targets of racist, sexist, and exclusionary attacks on social media. Preserving these active conversations and saving the public witness of events recorded in real time is important but not easy. Most social media platforms are commercial entities, so saving these conversations requires understanding terms of service for each platform, user rights, and advanced technical knowledge to harvest conversation streams. Led by archivist Bergis Jules, the Documenting the Now team has developed tools and workflows to enable saving of social media hashtags and streams for future research.[xvi] No matter the project, digital public historians encourage and facilitate active participation of communities to increase understanding of the past and contextualization of the present through digital means.

Computational Analysis

Digital history that requires computer programming languages to explore historical data through visualization is often referred to as computational analysis. This approach can be most helpful for exploring collections of digital sources and other types of data that can be visualized to frame research questions or expose the relationships among people, places, and ideas. Using spatial data, some digital historians interpret landscapes by generating maps. Exploring the constructions and connections of place and space are important when studying the spread of commodities, ideas, and people, as well as the impact of public policies on physical places. Through careful research of local records, Prologue DC’s Mapping Segregation in Washington, DC visualizes segregation in twentieth-century Washington, D.C., neighborhoods by mapping the restrictive covenants, block-by-block, across the city. Weaving together legal challenges, historical photographs, and other sources on a map, this project offers a good example of how placed-based storytelling can make systemic racism visible in concrete ways.[xvii]

Textual analysis, more commonly used in literature and rhetoric fields, offers methods for examining language use by identifying language patterns and themes based on combinations of words and phrases across bodies of texts (corpora). Historian Michelle Moravec employs these techniques when examining documents related to the women’s suffrage movement in the United States. Through analyzing the rhetoric amassed across six volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, Moravec can see how the white editors framed the voting rights movement’s rhetoric. By excluding radical voices and women of color who saw suffrage as one step toward achieving equal rights for all women, the compendium’s editors focused on issues pertinent to themselves—property rights of married white women.[xviii] These limitations are important to identify when researching a large body of sources. Since computational methods require digitized and machine-readable content, the absence of inclusive collections presents real challenges. Online collecting and recovery efforts mentioned earlier in the essay are an integral piece for creating an inclusive digital history.

Social network analysis helps digital historians to explore relationships between different entities and visualize them. The Linked Jazz project team, led by Cristina Pattuelli, spent years extracting and identifying names of jazz musicians, composers, and leaders through recorded transcriptions of oral histories, photographs, and documents using computational techniques. The team built a database of names and identified connections, such as band member, mentor, influencer, or collaborator. They then asked for assistance from historians, fans, and jazz musicians to identify and confirm the relationships and other biographical information from this community. Driven by metadata that links individuals across multiple collections, Linked Jazz generates visualizations that show the many connections of individuals lesser known in mainstream histories, such as Toshiko Akiyoshi, a prominent Japanese band leader and musician.[xix] Engaging in computational analysis requires a digital historian to create datasets, and data needs definition to be processed. Forcing uncertain information into a fixed value, such as a date or specific place, when source material may not offer that certainty creates tension for historians and may mean that a specific digital method cannot reasonably be employed as means for analysis. This also can make computational methods less accessible than other areas of digital history.

Challenges for the Field

Despite the field’s efforts to build an open and collaborative community, digital history methods can be exclusive and challenging to practice. Digital historians have worked to be inclusive of underrepresented and under-served communities in their project work, but they have not been as successful in expanding the corps of practitioners. Even still, efforts such as the multi-lingual Programming Historian, offer step-by-step lessons with sample data and content for learning different digital methods, free open source software, and workflows. Started in 2008 by William J. Turkel and Alan MacEachern, Programming Historian is now a free peer-reviewed publication supported by an active cohort of authors, editors, and reviewers committed to teaching, fostering, and growing an inclusive community of practitioners.[xx] Other efforts to increase capacity can be found through free professional development opportunities offered through the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Getty Foundation, and professional organizations, as well as fee-based courses at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute and many universities. National networks, such as RailsGirls, are working to give young women free training in computational thinking and programming and, in this way, seek to create a more inclusive workforce in the technology sector.[xxi] This essay shows that digital methods and projects offer dynamic ways for creating, publishing, and collaborating on inclusive history projects. While this essay does not address digital infrastructure, it is important to note that historians are contributing to these new methods and the scholarly communications ecosystem through the development of and contributions to free and open source software that undergirds much of the work cited here.[xxii] A major challenge for us, is to be active in conversations about preserving and sustaining the open digital infrastructure that makes this inclusive digital history work accessible for all in years to come.

Notes

[i] Library of Congress, American Memory, https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html; New York Public Library, Digital Schomburg, http://digital.nypl.org/schomburg/images_aa19/; Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, https://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/family-history-center; Family Search has grown tremendously since its launch in May 1999, as an outgrowth of the LDS Church’s Genealogical Society of Utah, https://www.familysearch.org/.

[ii] Omar Khan, Harappa: The Indus Valley and the Raj in India and Pakistan, original website content lives here http://old.harappa.com/, and the updated newly-designed site is found at http://harappa.com/.

[iii] Digital Library of the Caribbean, http://dloc.com.

[iv] P. Gabrielle Foreman, Jim Casey, Sarah Lynn Patterson, et al, The Colored Conventions Project, http://coloredconventions.org.

[v] Michelle Caswell, “Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annihilation,” The Public Historian 36, no. 4 (November 2014): 26-37, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2014.36.4.26.

[vi] Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Memory Book, 2007-2011: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/initiatives/memory-book; Laura Coyle, “Right from the Start: The Digitization Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture,” The Public Historian 40, no. 3 (August 2018): 292-318, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2018.40.3.292.

[vii] Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and American Social History Project, History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, http://historymatters.gmu.edu.

[viii] National Endowment for the Humanities, EDSITEment, https://edsitement.neh.gov/; Kelly Schrum, et al, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, TeachingHistory.org: National History Education Clearinghouse, https://teachinghistory.org.

[ix] Ruth Sandwell and John Lutz, Who Killed William Robinson? Race, Justice and Settling the Land, http://canadianmysteries.ca/sites/robinson/home/indexen.html.

[x] Dan Cohen, “A Million Syllabi,” DanCohen.org, blog, March 31, 2011, https://dancohen.org/2011/03/30/a-million-syllabi/; Chad Williams, et al, #Charleston Syllabus: https://www.aaihs.org/resources/charlestonsyllabus/.

[xi] Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, Scalar: https://scalar.me/anvc/; Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Omeka: http://omeka.org; WordPress Foundation, WordPress: http://wordpress.org; University of Minnesota Press, Manifold, https://manifold.umn.edu/; Matthew F. Delmont, Why Busing Failed, digital project, http://whybusingfailed.com/anvc/why-busing-failed/index.

[xii] African American Intellectual History Society, Black Perspectives, https://www.aaihs.org/black-perspectives. Black Perspectives won the American Historical Association’s Roy Rosenzweig Prize for Innovation in Digital History in 2017.

[xiii] Lauren Jae Gutterman, “OutHistory.Org: An Experiment in LGBTQ Community History-Making.” The Public Historian 32, no. 4 (November 2010): 96-109. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2010.32.4.96.

[xiv] Denise Meringolo, Maryland Historical Society, et al, Preserve the Baltimore Uprising, http://baltimoreuprising2015.org/.

[xv] Aleia Brown and Adrianne Russell, “We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest,” The Incluseum (blog), December 17, 2015, https://incluseum.com/2015/12/17/we-who-believe-in-freedom-cannot-rest/.

[xvi] Bergis Jules and Ed Summers, et al, Documenting the Now, https://www.docnow.io/.

[xvii] Prologue DC, Mapping Segregation in Washington, DC, http://www.mappingsegregationdc.org/.

[xviii] Michelle Moravec, “‘Under this name she is fitly described’: A Digital History of Gender in the History of Woman Suffrage,” Women and Social Movements 19, no. 1 (March 2015), http://womhist.alexanderstreet.com/moravec-full.html.

[xix] Cristina Pattuelli, et al, Linked Jazz, https://linkedjazz.org/.

[xx] The Programming Historian, https://programminghistorian.org/.

[xxi] National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of Digital Humanities, Institutes for Advanced Topics in Digital Humanities program, https://www.neh.gov/divisions/odh/institutes; Digital Humanities Summer Institute at University of Victoria, Canada, http://www.dhsi.org/; National RailsGirls, http://railsgirls.com/.

[xxii] Software is developed and maintained by historians and humanists at institutions, such as the Roy Rosenzweig Center for New Media at George Mason University and the Corporation for Digital Scholarship (Zotero http://zotero.org; Omeka http://omeka.org; and Tropy, http://tropy.org); Stanford University’s Humanities + Design Lab (Palladio, http://hdlab.stanford.edu/palladio/); and Alliance for Networking Visual Culture (Scalar, https://scalar.me/anvc/scalar/). Individuals contributing software include Stefan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell (Voyant Tools, https://voyant-tools.org/) and Lincoln Mullen (R packages: https://lincolnmullen.com/code/).

Suggested Readings

Brennan, Sheila A. “Public, First.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/83.

Caswell, Michelle. “Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annihilation.” The Public Historian 36, no. 4 (November 2014): 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2014.36.4.26.

Cohen, Daniel J., and Roy Rosenzweig. Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/.

Coyle, Laura. “Right from the Start: The Digitization Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture.” The Public Historian 40, no. 3 (August 2018): 292-318. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2018.40.3.292.

Gallon, Kim. “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/55.

Gibbs, Frederick W. “New Forms of History: Critiquing Data and Its Representations.” The American Historian, February 2016. http://tah.oah.org/february-2016/new-forms-of-history-critiquing-data-and-its-representations/.

Gutterman, Lauren Jae. “OutHistory.org: An Experiment in LGBTQ Community History-Making.” The Public Historian, 32, no. 4 (November 2010): 96-109. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2010.32.4.96.

Leon, Sharon. “Complicating a ‘Great Man’ Narrative of Digital History in the United States.” In Bodies of Information, Intersectional Feminism and Digital Humanities, edited by Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, 344-366. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Graham, Shawn, et al. Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope. London: Imperial College Press, 2016. http://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/.

Posner, Miriam. “What’s Next: The Radical, Unrealized Potential of Digital Humanities.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/54

Rosenzweig, Roy, et al. Clio Wired: The Future of the Past in the Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/rose15086.

Tilton, Lauren, et al, editors. American Quarterly Special Issue: Toward a Critically Engaged Digital Practice: American Studies and the Digital Humanities 70, no. 3 (September 2018). https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/13.

White, Richard. “What Is Spatial History?” The Spatial History Project, February 1, 2010. http://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/pub.php?id=29.

Author

~ Sheila A. Brennan is a digital public historian and strategic planner with over 20 years of experience working in public humanities. She has directed dozens of digital projects and published an open access digital monograph, Stamping American Memory: Collectors, Citizens, and the Post (University of Michigan Press, 2018).