Practitioners of disability history often model community engagement and wide-ranging access practices, and they insist on the value of disabled people and their histories. Interpreting disability history is one way historians and their communities, public or academic, can practice access and inclusion. Accessible and inclusive history must consider the history of everyone, including disabled people, and be accessible for disabled people. Interpreting disability history is linked to advocating for including people with disabilities in public life and therefore combats ableism, or the preference for able-bodied people over disabled people. Moreover, it promotes disability justice today.[i]

Language

Disability history almost always includes a note about language like this one; that is because language is constantly changing. Words disabled people use to talk about disability can vary from person to person. Words historians use to interpret disability change, and many words people used historically and continue to use today to talk about disability, in terms of lived experience or metaphorically, are offensive.

Most historians use contemporary words when interpreting disability history except when they are quoting a historical source. For example, when writing about someone who identified as a “cripple” in the eighteenth century, a historian might use that word if they are quoting a primary source, but they would likely use contemporary words or phrases such as “disabled person” or person with a “physical disability” when they are not quoting historical sources. Historians sometimes limit quoting historical sources because people in the past have used words and phrases like “cripple” or “deaf and dumb” to marginalize or exclude disabled people. Yet some people have reclaimed words like “cripple” and “crip” to assert power over ableist culture. Avoid outdated or offensive language (ex: “handicapped parking” or “handicapable”). People practicing disability history should consult the contemporary disability community or thoughtful language guides. If you are not sure where to start, get in touch with an advocacy organization local to you.

About Me

Similar to providing language notes, historians who interpret disability history sometimes provide information about their relationship to the field. For example, I have experienced temporary disability and have cared for chronically ill family members, but I do not identify as a disabled person. I have studied disabled people in history and have learned from and collaborated with disabled people on a variety of programs and in organizations. I have a lot to learn about disability history and how to assert disability justice. I like to disclose this information to model transparency as well as so people with lived experience or scholarly expertise I do not possess can contribute to the work I am trying to accomplish.[ii]

A History of Disability History in the United States

In the United States, disability history is not a new historical subfield, and it intersects with all historical subfields since disabled people were a part of every historic community. When historians use the phrase “disability history,” they are usually referring to the history of people in the past whose bodies and/or minds were considered atypical and the role ableism played in that history. For those who are new to disability history, one way to explain this definition from a medical perspective is to note that disability history is about people with physical or sensory disabilities and people who would identify today as neurodiverse, mad, or chronically ill.[iii] Interpretative tactics and historiographies vary depending on the nature of disability, historical actors, and contemporary politics. Such work is not confined to the United States. Disability historians and advocates have also been hard at work in, and on, other parts of the world.

Historians typically cite the 1980s as the decade when disability history began to flourish. In the year 2004 the Disability History Association (DHA) was formally established, and, in 2003, historian Catherine Kudlick published a seminal essay in The American Historical Review called “Why We Need Another ‘Other.’” In 2005, historians Susan Burch and Katherine Ott co-edited a special issue on disability history and public history for The Public Historian. According to a DHA newsletter, the American Historical Association (AHA) added “disability history” to its list of subfields in 2006 and featured disability history in its November 2006 issue of Perspectives.[iv] Other recent scholarly landmarks include (but are not limited to) historian Kim E. Nielsen’s 2012 synthesis of disability history in the United States and the 2018 Oxford Handbook of Disability History, edited by Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick, and Kim E. Nielsen. Disability studies is a related, interdisciplinary field.[v]

People and historians in and of the United States who are unfamiliar with the vastness of disability history often characterize the field as one that focuses on modern civil rights history, beginning when the United States Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. The act requires independent, physical and programmatic access to private and public spaces and events for disabled people. It marked a moment when the federal government declared that disabled people had civil rights to protect. It helped bring national attention to disabled people and disability rights. The act also helped galvanize the study of disability history itself. But the passage of the ADA did not mark the point in time when historians first identified primary sources for interpreting disability history, when historians started thinking about disability as having a past, or when professionals in public heritage settings started thinking about accessibility for disabled people.

There always were disabled people in the world. Archaeological evidence from before the common era can help us learn more about this long history. As my research and that of my colleagues show, in the context of early British North America, disabled people were well-integrated and visible in everyday life. Many people have not given this fact much thought let alone analyzed its historical meaning or contemporary resonance.

Prior to the 1980s, historians and allied specialists thought about disability as having a past. Historian John Demos, for example, in his book A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony (1970), mentioned that in the early years of colonization, European families often cared for disabled settlers, whether they knew them or not.[vi] In another instance of early interpretation of disabled people in history, anthropologist Jacob Gruber tried for ten years to find a home for an article about a woman who used an artificial leg, but one editor, for example, wrote he was “skeptical” about “her wooden leg and new set of teeth.” Ultimately, Gruber’s published piece focused on other aspects of her story.

Staff and volunteers in museum settings were thinking about what we would call accessibility today long before the ADA was passed. Staff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, for example, planned field trips for disabled children in the early twentieth century.[vii] Colleagues at other museums in the country did as well.

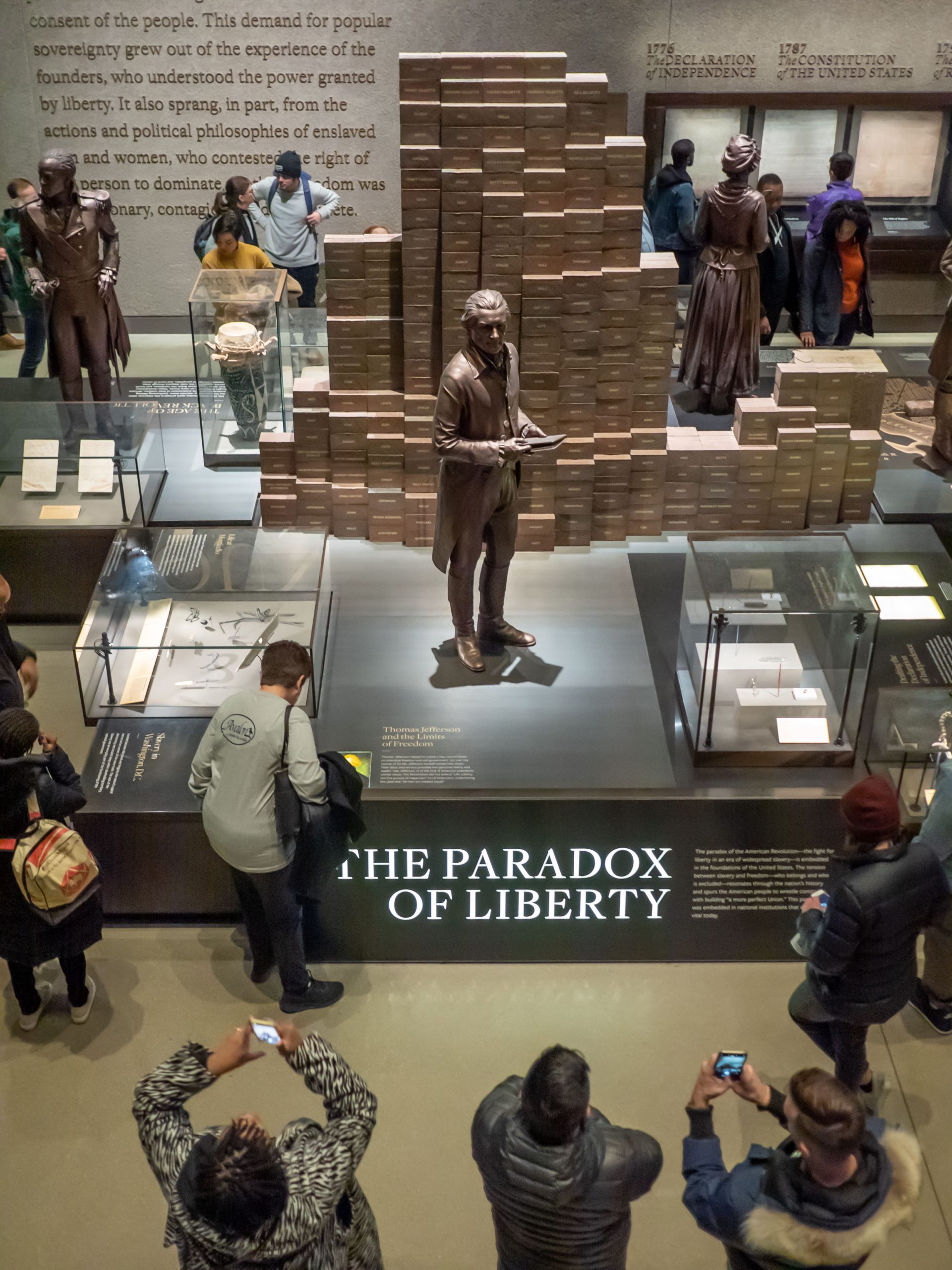

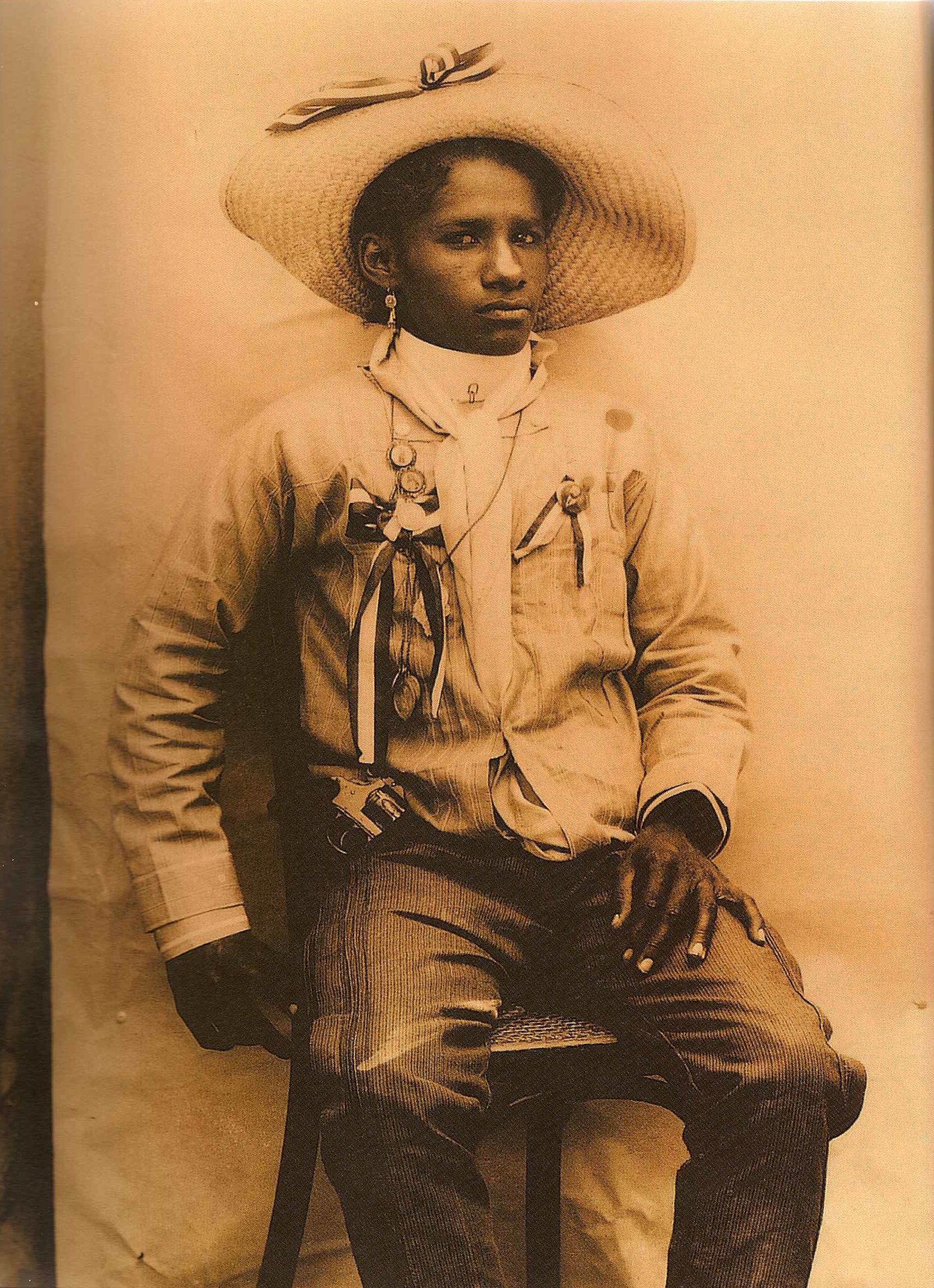

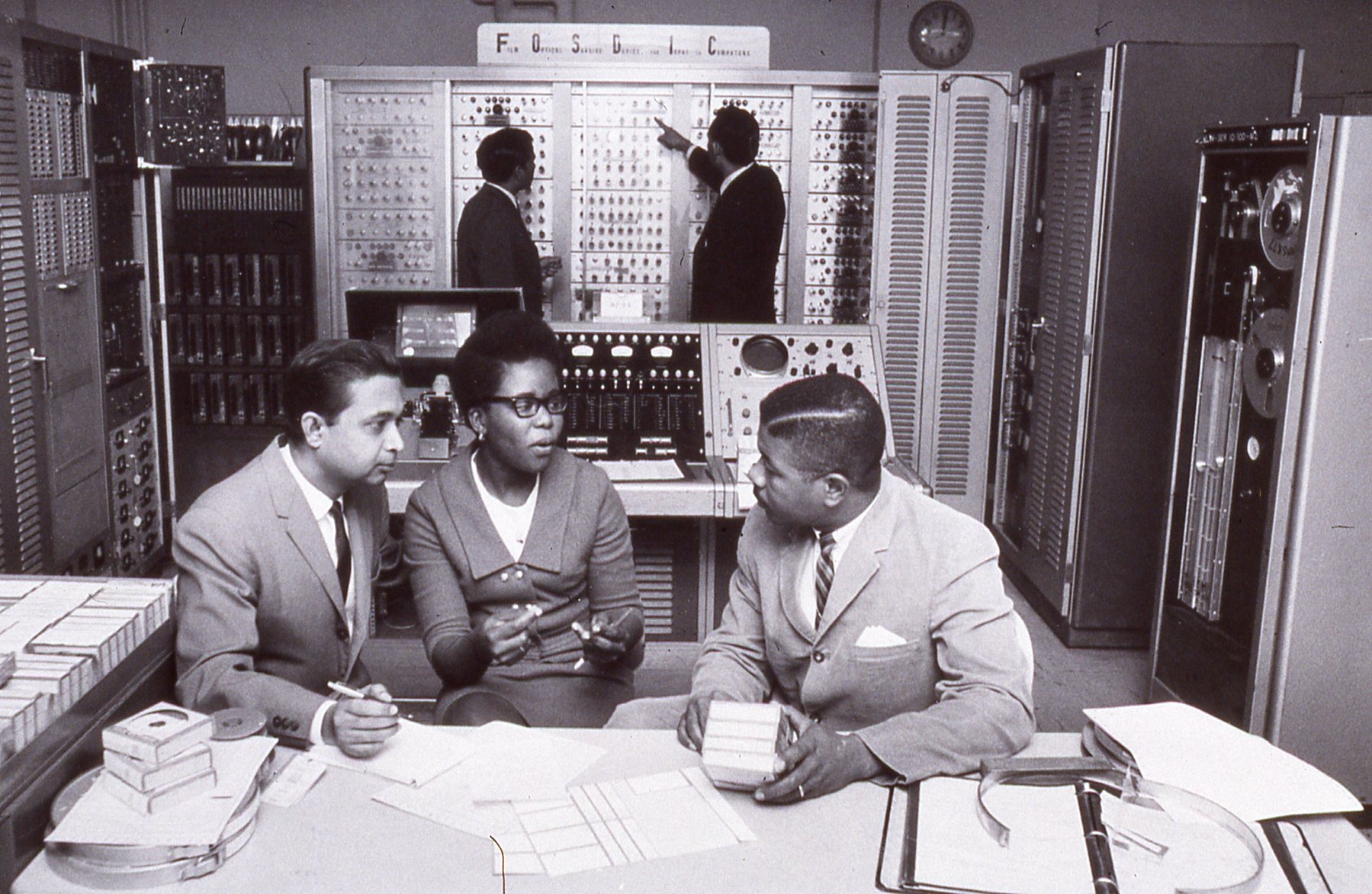

Disability history—and the fact that people have been slow to recognize that disability has a history—cannot be understood without discussing ableism. Ableism is often perpetuated because public and scholarly understandings of disability history are influenced by both particular histories of disability from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the persistence of ableism today. For example, many people are familiar with—or their perception of disabled people is affected by—some of the following facts: the history of disabled people in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (pre-ADA) often includes histories of people institutionalizing people against their will; people enacting and enforcing laws restricting disabled people in public life; people enacting and enforcing laws restricting immigration of disabled people; and people placing disabled people in education settings that separated them from others.[viii] Despite the fact that, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people marginalized disabled people in these ways, they were still a part of public life, as the image below suggests. As activist Alice Wong’s Disability Visibility project notes, for all these reasons and more, many of us have not realized the visibility of disabled people historically or today.

Disability History’s Relevance

Disability history is relevant for everyone. It often intersects with histories of war, industry, racism, institutionalization, medicine, public health, civil rights, gender, and design. But it is also about everyday life. Almost any historic site or museum can and should interpret disability history, and everyone’s life involves disability of some form or another. Disability history’s meanings vary depending on context. I encourage you to tell disability histories where you work or volunteer, and if you do, center the voices of disabled people themselves. After all, disability history teaches us the history of access and expands our understanding of what accessibility history and living can look like.

People unfamiliar with disability history often equate it to medical history. Disability history and medical history are not the same fields, but they are related and have spurred important discussions about the nature of that relationship.[ix] Disability history typically emphasizes living with disability rather than diagnosing, curing, or overcoming it, so any discussion of medicine should be carefully considered. For example, gout is a disabling form of arthritis, and its significance in early America cannot be understood without discussing the way doctors and ordinary people tried to cure it. But it is because of this fact that a disability history of gout in early America should emphasize living with and managing it.[x] In public history settings, disability history and medical history often intersect in discussions about the display of human remains.

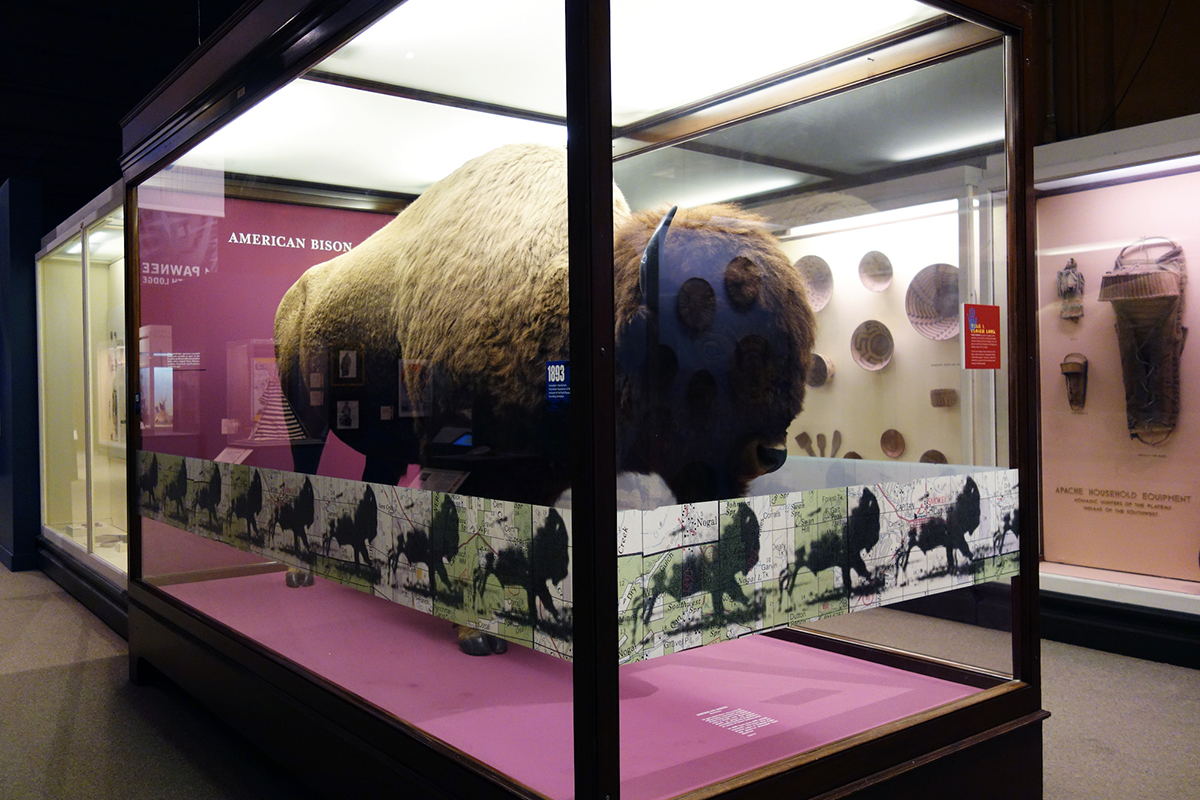

Disability history in public settings has taken many forms. The Smithsonian National Museum of American history, under Katherine Ott, has produced several disability-related resources including, for example, the 2013 online exhibition EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America. The New York State Museum exhibited suitcases and contents left behind by people who had been incarcerated at the Willard Psychiatric Center. More recently, the National Park Service (NPS) initiated a series of projects aimed to highlight disability history at NPS sites and is working on a disability history handbook. Non-federally affiliated sites and individuals have also delved into disability history. Some groups are advocating for a national museum of disability history. Archivists and oral historians have also centered disability in the work they do as public historians and have written pieces featuring reflections and best practices. Disability history is reaching all areas of public history. What are you doing to highlight it in your work?

Disability Justice-Centered History Work

In addition to interpreting disability history, public historians should make all history content accessible for disabled people. Disability justice should permeate the way historians approach their everyday work and advocacy within work and service settings. In other words, public history work and service settings should be accessible and inclusive regardless of whether they have anything to do with disability history. Many disability advocates believe compliance with the ADA remains inadequate and that compliance with the ADA should not be the goal. In addition, others assert that the disability rights movement marginalized some individuals and groups. Historians can use critiques of the ADA to advance issues in disability justice in their communities in collaboration with disabled individuals and groups, through the interpretation of disability history.

Making public history work accessible and inclusive is, as indicated by the following suggestions, an ongoing process. Start doing what you can and build your practice from there.

Foster the preservation of disability history and interpret disability history in collaboration with disabled people. Include contemporary disabled people in the work of interpreting and making accessible disability history—and be sure to compensate them.

Recruit and hire disabled people and craft recruitment materials in a way that it is inclusive of disabled people.

Create positions in public history that are about disability history or accessibility.

Create an accessibility guide (some examples are here and here) for the place where you live, work, or volunteer. It might include facts such as the number of steps up to your front door; restroom accessibility (including whether they are for families, any gender, etc.); and COVID-19 access information, such as masking and vaccination policies.

Assess places and programming intersectionally and in collaboration with the community to improve access and inclusion. Partner with and consult other historically marginalized groups such as people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals, but also people who promote sustainability and environmental justice. Advocating for accessibility might also involve dismantling other historical injustices.

Insist on basic accessibility measures at conferences and other meetings such as:

- Providing access copies. Access copies are outlines or full copies of a talk or other interpretive material in accessible word processing formats. They are helpful for people who prefer to process information visually or through reading, including after an event. They are also helpful for people who are blind or who have low vision or who are deaf or hard of hearing. When provided digitally, they can include hyperlinked text to resources not mentioned in the presentation or program itself.

- Offering specific accommodations in registration materials so disabled people do not have to ask you themselves.

- Designing programming to expand access to the greatest extent possible through hybrid and remote participation options.

- Requiring participants to use microphones (in-person) and that organizers arrange for live-captioning (not auto-generated) and/or American Sign Language interpretation.

- Including disabled people on the planning team from the start.

Build accessibility into classroom settings and re-shape your approach to teaching and accessibility. Learn more about how you can avoid ableism in the academy.

Encourage funders to create opportunities for disabled people; ensure the application process and the award itself is accessible and inclusive of disabled people; and require grantees make their history work accessible and inclusive of disabled people. For example, an accessible research fellowship might allow for remote work. A local granting organization might require its recipients of programming grant money to include an accessibility questionnaire upon registration and/or a budget line for accessibility needs. Or, a funder might encourage applicants to build accessibility research and evaluation into their projects.

In classroom, public program, and office settings, aim for access and inclusion that centers disability justice. When someone asks for what might be considered an accommodation under the ADA, implement the accommodation without requiring someone to go through a bureaucratic and demeaning accommodations process that often does not work.

Many people will fear litigation when you mention the ADA. Advocate for, practice, and talk about access and inclusion for disabled people that minimizes compliance and fear. As Aimi Hamraie and the Critical Design Lab’s Mapping Access project assert, “community-generated versions of accessibility codes . . . can create new standards for accountability” that put “ADA compliance” in the background.

Advocate for the places where you live, work, or volunteer to integrate disabled perspectives into their diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiatives. Disability is often inadvertently left out.

Evaluate and reevaluate your access and inclusion practice as much and as often as you can. Much like historians consider the interpretation of history as never being over, disability advocates consider access to be a process that is never complete.

Share these resources with friends, colleagues, and family. Center access and inclusion in your life.

Notes

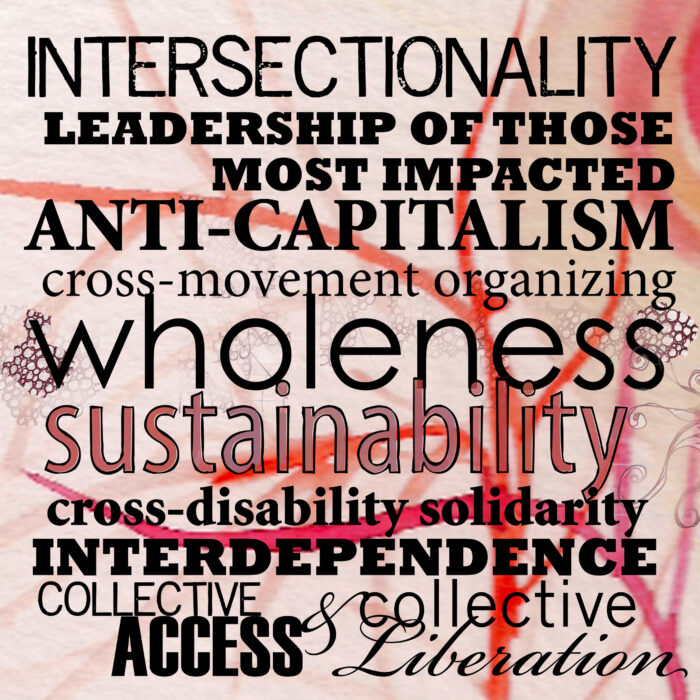

[i] Disability justice could easily be a separate Handbook entry. But to get started on learning more about it, try the following resources: Patty Bern, “Disability Justice – a working draft,” June 10, 2015, https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne; Rabia Belt, “Disability, Debility, and Justice,” Harvard Law Review Blog, March 4, 2021, https://harvardlawreview.org/blog/2021/03/disability-debility-and-justice/; Nomy Lamb, “This is Disability Justice,” The Body is Not an Apology, September 2, 2015; Mia Mingus, “Changing the Framework: Disability Justice: How our communities can move beyond access to wholeness,” Leaving Evidence, February 12, 2011, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice/; Vissa Thompson on The Harriet Tubman Collective, “Disability Solidarity: Completing the ‘Vision for Black Lives,’ Huff Post, September 7, 2016, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/disability-solidarity-completing-the-vision-for-black_b_57d024f7e4b0eb9a57b6dc1f; and Alice Wong, The Disability Visibility Project, https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/.

[ii] David Serlin, “Making Disability History Public: An Interview with Katherine Ott,” Radical History Review (Winter 2006): 201.

[iii] This list is incomplete and individuals may refer to disability in a variety of ways not represented here.

[iv] “Announcements,” Disability History Association Newsletter 2, no. 2 (Fall 2006), http://dishist.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/DHANewsletter-2006-Fall.pdf and “Forum on Disability in History,” Perspectives 44, no. 8 (November 2006), https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/november-2006-x42670.

[v] The focus here is on disability history in what would become the United States, but historians are doing wonderful work on disability history in the Global South.

[vi] John Demos, A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 80-81.

[vii] Nicole Belolan, “An ‘effort to bring this little handicapped army in personal touch with beauty’: Democratizing Art for Crippled Children at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1919-1934,” New York History 96, no. 1 (Winter 2015): 38-66.

[viii] Sandra M. Sufian, Familial Fitness: Disability, Adoption, and Family in Modern America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 110-113.

[ix] For more about the relationship between medical history and disability history, see Beth Linker, “On the Borderland of Medical and Disability History: A Survey of the Field,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 87, no. 4 (2013): 499-535, and Catherine Kudlick, “Social History of Medicine and Disability History,” in The Oxford Handbook of Disability History, eds. Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick, and Kim E. Nielsen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 105-124.

[x] “The Material Culture of Gout in Early America,” in Elizabeth Guffey and Bess Williamson, eds., Making Disability Modern: Design Histories (New York: Bloomsbury, 2020), 19-42 and “‘Confined to Crutches’: James Logan and the Material Culture of Disability in Early America,” Pennsylvania Legacies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall 2017): 6-11.

Suggested Readings

Here are just a few projects, reflections on projects, or suggested methodologies that exhibit some or all the tips above.

Accessible Campus Action Alliance. “Beyond ‘High-Risk’: Statement on Disability and Campus Re-openings.” 2020. https://bit.ly/accesscampusalliance.

Blackie, Daniel, and Alexia Moncriff. “State of the Field: Disability History.” History, July 20, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-229X.13315.

Disability and Industrial Society: A Comparative Cultural History of British Coalfields, 1780-1948 (2011-2016).

Belolan, Nicole. “Over-the-hill canes and ideal bodies: teaching disability history as public history.” History@Work. February 7, 2018. https://ncph.org/history-at-work/teaching-disability-history-as-public-history/.

Bucciantini, Alima. “Getting in the Door is the Battle.” AASLH Blog, American Association for State and Local History. January 22, 2019. https://aaslh.org/getting-in-the-door/.

Burch, Susan. Committed: Remembering Native Kinship in and Beyond Institutions. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021. Available as an open-access E-Book.

Clary, Katie Stringer, and Carolyn Dillian. “Technical Leaflet 290: 3-D Technologies for Exhibits and Programming.” American Association of State and Local History. https://learn.aaslh.org/products/technical-leaflet-290-3-d-technologies-for-exhibits-and-programming.

Clare, Eli. Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Denial, Catherine. “A Forward to Designing for Care.” August 23, 2022. https://hybridpedagogy.org/a-foreword-to-designing-for-care/.

The Disability History Association

Dolmage, Jay Timothy. Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017. Available as an open access E-book.

Grigely, Joseph. “Inventory of Apologies.” VoCA Journal. December 7, 2020, https://journal.voca.network/inventory-of-apologies/.

Hamraie, Aimi. “Accessible Teaching in the Time of COVID-19.” Critical Design Lab. March 10, 2020. https://www.mapping-access.com/blog-1/2020/3/10/accessible-teaching-in-the-time-of-covid-19.

_____. “Mapping Access Toolkit,” Critical Design Lab. https://www.mapping-access.com/mapping-access-methodology/

Higgins, Jason A., UMass Oral History Lab and Ashley Woodman, with Catherine Kudlick and Fred Pelka, narrated by Emily T. H. Redman. “Episode 8: Oral History and People with Disabilities.”

Kudlick, Katherine. “Subversive Access: Disability Goes Public in the United States.” Public Disability History. May 24, 2016. https://www.public-disabilityhistory.org/2016/05/subversive-access-disability-history.html.

Lewis, Talila A. “Working Definition of Ableism: January 2022 Update.” Blog. January 1, 2022. https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/working-definition-of-ableism-january-2022-update.

Meldon, Perri. “The NPS Disability History Handbook: Collaboration, process, and community.” History@Work. December 7, 2023. https://ncph.org/history-at-work/the-nps-disability-history-handbook/.

Nair, Aparna, and Kylie M. Smith. “We’re Historians of Disability. What We Just Found on eBay Horrified Us.” Slate. July 21, 2022. https://slate.com/technology/2022/07/vintage-asylum-records-found-on-ebay-history-of-disability.html.

O’Toole, Corbett Joan. Fading Scars: My Queer Disability History. Fort Worth: Autonomous Press, 2015.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.

_____. “where do we go from here? a roundtable from some disability justice organizers in this the only moment in time.” Disability Visibility Project blog. May 21, 2023. https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2023/05/21/where-do-we-go-from-here-a-roundtable-from-some-disability-justice-organizers-in-this-the-only-moment-in-time/.

Mingus, Mia. “Changing the Framework: Disability Justice: How our communities can move beyond access to wholeness.” Leaving Evidence. February 12, 2011. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice/.

Ott, Katherine. “Disability Things: Material Culture and American Disability History, 1700–2010.” In Disability Histories, edited by Susan Burch and Michael Rembis, 119-135. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Samuels, Ellen. “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time.” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, No. 3 (2017). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684.

Schalk, Sami. Black Disability Politics. Durham: Duke University Press, 2022.

Serlin, David. “Making Disability History Public: An Interview with Katherine Ott.” Radical History Review (Winter 2006): 201.

Sins Invalid. “10 Principles of Disability Justice.” https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice.

Valldejuli, Jorge Matos. “The Racialized History of Disability Activism from the ‘Willowbrooks of this World.’” The Activist History Review. November 4, 2019. https://activisthistory.com/2019/11/04/the-racialized-history-of-disability-activism-from-the-willowbrooks-of-this-world1/.

Virdi, Japreet. Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Intersection of Race and Disability History Project. Western Pennsylvania Disability History and Action Consortium. https://www.wpdhac.org/intersection-of-race-and-disability-project/.

Wong, Alice, ed., Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the 21st Century. New York: Vintage, 2020.

Note: This essay includes a discussion of legal issues but should not be interpreted as legal advice. The author is grateful to the many disability historians and advocates she has learned from. She has done her best to link to or cite as many as possible and welcomes discussion as access and inclusion evolves.

Author

~ Nicole Belolan is a Consulting Public Historian and Independent Scholar. She publishes on disability history and leads workshops on disability history and access and inclusion. She has been on the Board of the Disability History Association since 2019. Belolan would like to thank Susan Burch and Kasey Grier for many conversations that have helped shape her work in this field.