Never monolithic, the U.S. suffrage movement catalyzed a process through which women determined what roles they sought in the polity and strategized ways to obtain them. Examining this process highlights the ways that true change in democracy begins with social justice activists, and seldom with elites. The inadequacies of the U.S. Constitution set into motion a movement that grew over time, drawing allies, confronting and surmounting challenges, and persisting until women’s demands were met. Even today, the Constitution does not guarantee its citizens the right to vote; it only guarantees that the right to vote cannot be denied on the basis of race (the Fifteenth Amendment) or sex (the Nineteenth Amendment). The commitment of women and their male supporters to expanding citizenship for women tells us much about the meanings of equality and citizenship in a democracy. Gender, race, class, and nationality intersect with the women’s suffrage movement in profound ways, and celebratory histories of the movement are complicated by some of its most prominent leaders’ racism and xenophobia and their inability to embrace full inclusivity. Yet the movement remains relevant in a democracy still struggling with the vision of a more perfect union.

From the Founding to the Civil War

The U.S. Founders modeled the U.S. government on the oldest participatory democracy in the world, the Confederacy of the Haudenosaunee, wherein each member nation (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) has unique powers and responsibilities. They did not, however, embrace the Haudenosaunee principle of women’s political authority. While the Founders adopted aspects of governance from Indigenous nations, western models of exclusivity continued to hold sway and they rejected political roles for women in their model for the United States. In addition, the Founders left the details of voting rights to the states, thereby establishing a model with no clear guarantees of equal citizenship rights.

In the early national period, voting rights differed—sometimes significantly—by state. Examples of state-based voter qualifications included property ownership, class, religion (especially for Jews, Quakers, Catholics, and atheists), race, and gender. Black people and women in New Jersey voted from 1776 until 1807 when male legislators decided their votes affected election results and changed “he or she” to “free, white, male citizens,” disfranchising all women and men of color in the state. New York allowed Black male property owners who paid taxes on property worth at least $250 to vote after 1821; white men did not have property requirements. Women in a few states could vote on local issues.

In the 1830s and 1840s, as the abolition movement gained traction, women who worked for the end of slavery recognized their oppression based on sex. Many of the earliest women’s rights activists came from the anti-slavery ranks. Angelina Grimké, born into a slave-holding family in South Carolina, called for equal rights (including voting rights) in a resolution at a Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society of New York convention in 1837. The call created upheaval in her mostly white audience but clearly linked the end of slavery with the need to expand rights for women. The women’s rights movement also drew on Native American influences. In July 1848, Quaker Lucretia Coffin Mott, inspired by Seneca women exercising authority at the Cattaraugus Community, helped Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Jane Hunt, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton organize the first Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, NY. From then on, a small, but growing cadre of activist women demanded equal rights through their writing, speeches, petitioning, and conventions.

Setting aside their equal rights goals during the Civil War (1861-1865), white and Black women supported the Union war effort and the demise of enslavement. At war’s end, federal legislators sought to reconstruct the country through three constitutional amendments. The Thirteenth Amendment (ratified in 1865) officially abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868) made former enslaved people citizens, but specifically excluded Native people on reservations. Additionally, in Section 2, it defined a citizen as male, using the word for the first time in the Constitution. The Fifteenth Amendment (ratified in 1870) enfranchised those male citizens. The thousands of Black men who served the Union army strengthened the connection between voting rights and military capability. Instead of universally enfranchising all adult citizens, this process led to conflict between those suffragists advancing Black male voting rights and other proponents of women’s suffrage.

The Potential of Universal Suffrage

The American Equal Rights Association, founded in 1866, challenged the male descriptor of a voter in debates prior to the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Association, comprised of Black and white women’s rights activists and former abolitionists, sought universal suffrage—a term meaning that the right to vote is based on adulthood, regardless of the race or sex of the person. Legislators flatly refused to consider Indigenous people in this debate. In 1866-67, Association members attempted to convince delegates to the 1867 New York State Constitutional Convention to remove the word “male” from voter eligibility, hoping it would influence other states to do the same. When the Association failed in its goal, white suffragists increasingly expressed their frustration in racist and exclusionary terms.

Between 1868 and 1873, suffragists used a “New Departure” strategy to test the premise that the Fourteenth Amendment did not exclude women. Historian Ann Gordon and her team compiled a comprehensive list of hundreds of Black and white women who attempted to vote in this period in the appendix of volume II of The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. In extreme cases, most famously that of Susan B. Anthony, authorities arrested and fined women who attempted to vote. In Minor v. Happersett (1875) the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution did not give women the right to vote, ending the experiment of hundreds of women who attempted to vote in these years. Eventually, a federal court found in John Elk v. Charles Wilkins (1884) that because Native people were not citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment, they also could not vote. Even if Indigenous men lived off the reservation and paid property taxes, the federal government provided no paths for naturalization or citizenship for them.

The American Equal Rights Association had split into two new organizations after states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. The National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Stanton and Anthony in New York, now focused on passing a constitutional amendment to enfranchise women. Black women including Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Harriet and Hattie Purvis, and Charlotte E. Ray, who had long worked with the leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association, joined them. At the same time, African Americans Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Charlotte Forten, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, and others who supported a state-by-state enfranchisement strategy, joined the American Woman Suffrage Association, directed by Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell in Massachusetts. Sojourner Truth collaborated with both organizations. Black and white women had long been establishing suffrage clubs in villages, towns, and cities across the nation to influence the electorate. Educator Sarah Smith Garnet, for example, helped found the Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn in the late 1880s. Twenty-four states allowed women to vote in school elections by the end of the decade. Many activists saw these achievements as hopeful.

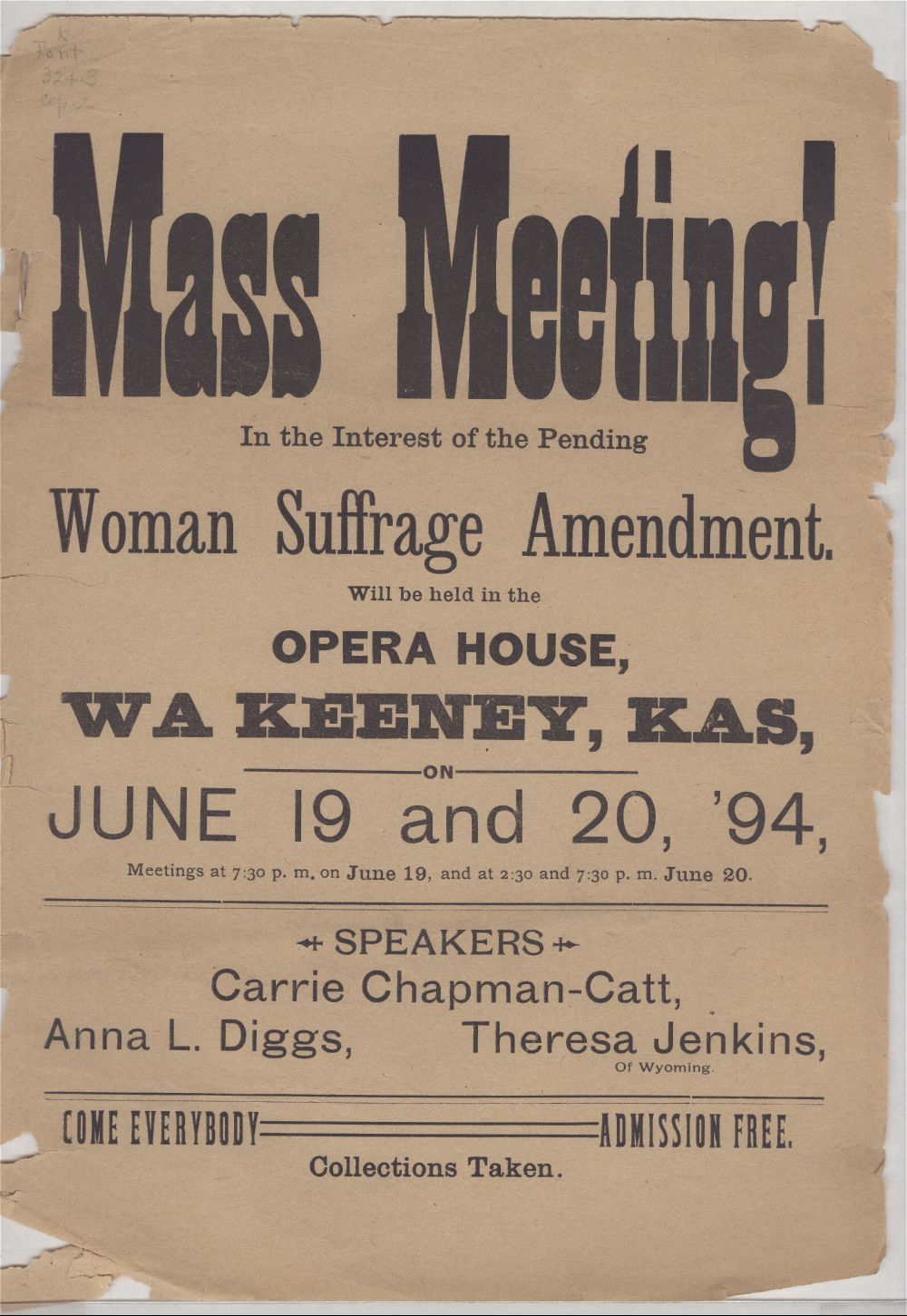

By the 1890s, western territories and states inspired suffragists to persist in their campaigns. Wyoming and Utah territories in the West had long supported women’s right to vote, primarily to meet the citizen requirements for statehood. Wyoming kept women’s voting rights when it gained statehood in 1890. Colorado became a state in 1876; although Catholic and Hispanic men opposed a referendum to enfranchise women the following year, they made up a smaller percentage of voters by 1893. With the help of African American leader Elizabeth Piper Ensley and white suffragists in the Non-Partisan Equal Suffrage Association, that year Colorado became the first state to enfranchise women by a popular referendum. Six years after Idaho became a state in 1890, its women won the right to vote. And Utah’s women had suffrage from the beginning of its statehood in 1896. Non-Native women of color in these states do not seem to have been targeted for disfranchisement. Meanwhile, at the federal level, Congress first debated a women’s suffrage amendment in 1878. Tellingly, members of Congress rehashed essentially the same arguments for another forty years.

Increasing Conservatism in the Suffrage Movement

To reduce fears of what the women’s rights movement might mean more broadly, activist leaders focused less on more radical demands such as dress reform or a woman’s right to divorce. This narrowing of goals to concentrate on suffrage reflects a period of increasing conservatism. When the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1890 to consolidate their energies, they established the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which had officially endorsed women’s suffrage in 1881 under the leadership of Frances Willard, also joined the campaign. The Union supported limits on religious freedom (a reaction to increased non-Christian immigration, including Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe) and the more conservative approach demanded by the leadership.

In protest, Matilda Joslyn Gage, then writing Woman, Church, and State, which connected women’s oppression to organized religion, resigned. She formed a separate organization, the Woman’s National Liberal Union, to promote women’s suffrage and the separation of church and state, and she edited The Liberal Thinker. Anti-suffrage women in New York and Massachusetts established their own organizations by 1895; anti-suffragists in other states followed their lead. Anti-suffragists resisted the changes that they feared suffrage would require of women and encouraged all women to remain in the private sphere. When anti-suffragists published their arguments, suffragists found it necessary to refine their own positions in response, revitalizing the movement and broadening its appeal. The public found the suffrage and anti-suffrage debates to be highly entertaining and newspapers and magazines increasingly published suffrage news.

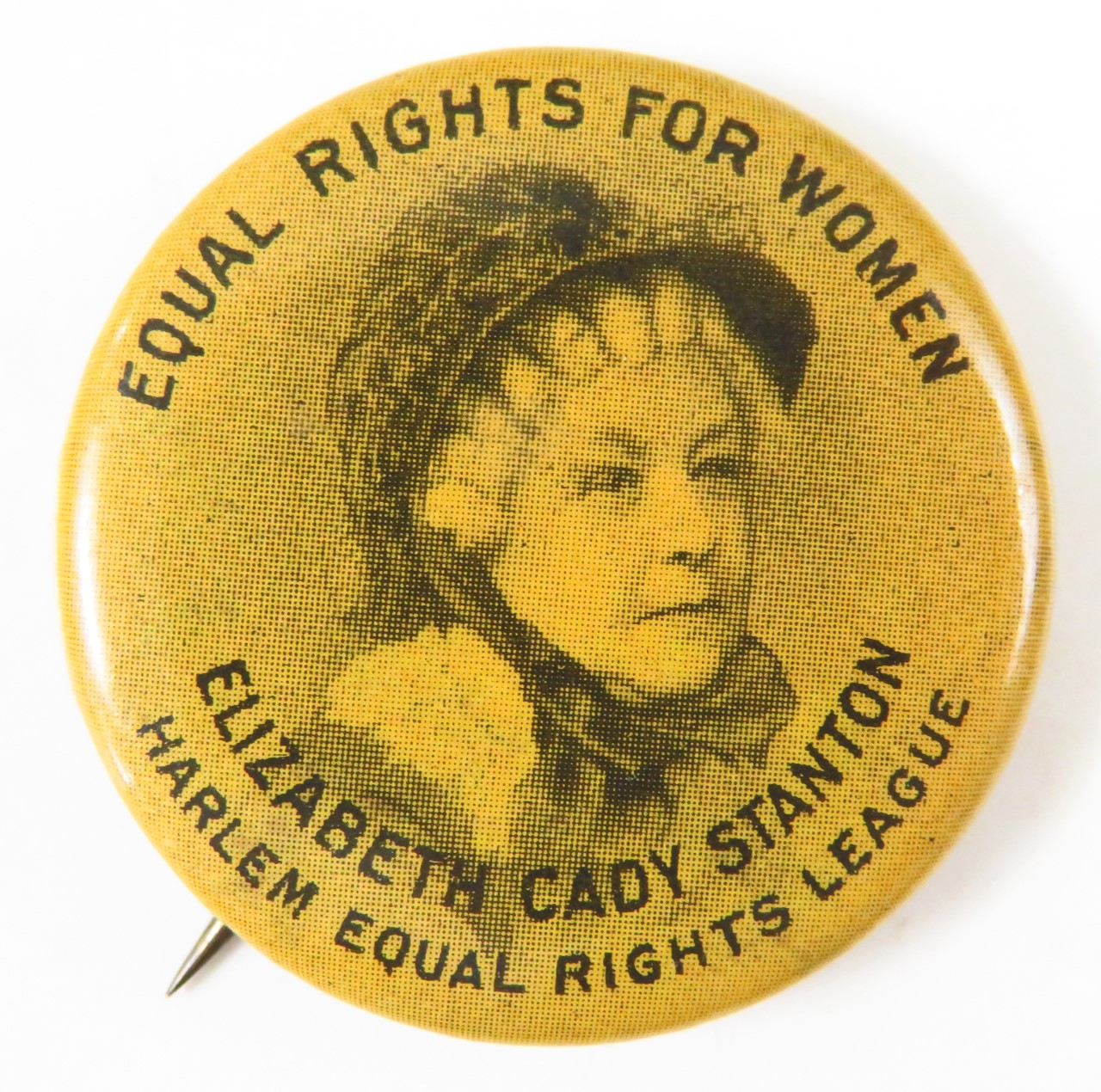

As “new woman” suffragists benefitted from higher education and greater social freedom, they appropriated innovative technologies and media to promote their cause. The material culture of suffrage included wearing the purple, white, and gold suffrage colors and jewelry to all kinds of public events, and distributing stamps, postcards, and letter paper. They called friends on the telephone, used automobiles as speaking platforms, and designed and marketed fashionable clothing, playing cards, games, china, jewelry, ribbons, buttons, toys, and souvenirs. Pro-suffrage activists also found journalism to be compatible with marriage and motherhood, and they frequently provided copy to newspaper and magazine editors. When anti-suffragists claimed that “real women” did not need political power and that suffragists “unsexed” themselves by stepping out of their appropriate sphere, suffragists held beautiful baby contests and demonstrated their cooking abilities. In the process, they simultaneously undermined and reinforced traditional ideas of femininity.

Suffrage and the Quest for Citizenship

Indigenous, Latin American, and Hispanic/Latinx women related women’s suffrage activism to their quest for self-determination and citizenship. American Indian Association member Marie L. Bottineau Baldwin (1863-1952, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa) and her colleague Zitkala Ŝa (1876-1938, Yankton Sioux) worked tirelessly for rights for Indigenous people. Both publicly supported women’s suffrage. Californian Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez (1881-1977) advocated for suffrage, translating documents into Spanish during the successful 1911 campaign. In New Mexico, Adelina (Nina) Otero-Warren also used Spanish to advocate for women’s suffrage during the debates leading to statehood in 1912. Nevertheless, New Mexican women had to wait until the signing of the Nineteenth Amendment to vote in their state.

In other efforts to broaden support for women’s right to vote, suffragists targeted the burgeoning immigrant and working-class population. Male immigrants who became citizens could vote, and suffragists sought their support. For example, in New York City, suffragists distributed propaganda in the languages of the new immigrants. They published campaign literature and broadsides in Greek, German, Russian, Italian, Irish, and other languages. Suffrage parades featured sections of various immigrant groups or African American women. Over seventeen thousand participants, including Chinese American Mabel Ping-Hau Lee, marched in the huge suffrage parade in New York City in 1912. Although she could not vote because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Lee’s appearance reminded observers of the promise of women’s enfranchisement in connection with the recent revolution in China.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, women’s suffrage activism dominated political life in the United States and all current events seemed connected to women’s quest for the franchise. It seemed that no one could remain neutral on the issue any longer. Political party leaders found themselves required to take a stand on women’s right to vote, competing against the more radical anarchists and the Socialist party, as well as the labor unions, for membership support.

State-by-State Successes

By 1913, women in nine states—Wyoming (1890), Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), Idaho (1896), Washington (1910), California (1911), Oregon (1912), Kansas (1912), and Arizona (1912)—had the power of the franchise. These enfranchised women then could publicly advocate for women’s suffrage in the states where women still had no voting rights. On March 3, 1913, thousands of women and their male supporters marched in another huge parade, organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns of the NAWSA’s Congressional Committee on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in Washington, DC. Although warned that whites would oppose African American marchers, Paul followed the official policy of NAWSA and “quietly” accepted twenty-two Delta Sigma Theta Sorority sisters from Howard University, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and other Black women who joined the parade as marchers. While newspapers printed photographs of white participants, a few artists focused on the participation of Native and Asian American women marchers in their sketches or cartoons. When some of the hostile onlookers became violent toward all the marchers, police looked the other way and officials called on the U.S. Cavalry to restore order.

Picketing the White House

Alice Paul and her supporters began picketing the White House in January 1917. Holding the Democratic Party, with the president at its head, responsible for keeping women disfranchised, picketers, known as “silent sentinels,” held banners quoting the president. Women from all over the country traveled to Washington to take up banners; Mary Church Terrell and her daughter joined them. After the declaration of war against Germany in April, a once sympathetic public and press became increasingly hostile to picketers they perceived as unpatriotic. By June, police began arresting women for minor charges such as obstructing the sidewalk. When they refused to pay the fines, the judges sent them to Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Over the eighteen-month period of the picketing, 168 women went to prison; many of them engaged in hunger strikes and suffered forcible feedings.

Because of the picketers, or perhaps despite the controversy they caused, 1917 marked a tipping point in the suffrage movement. New York women won full suffrage by the November 6 referendum. Nebraska, Michigan, Vermont, Arkansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Rhode Island approved full or partial suffrage for women that year. By the end of November, public outrage over the treatment of the incarcerated picketers forced their release from Occoquan. A highly experienced and determined cohort of women could then shift their attention from state campaigns into winning a federal amendment.

Although Wilson announced support for women’s suffrage as a “war measure” in 1917, members of Congress procrastinated on amending the Constitution. After several failed attempts beginning in January 1918, the proposed amendment, stating that the right to vote shall not be denied on account of sex, passed the House of Representatives in May 1919 and passed the Senate the following month. Suffragists remained vigilant as across the country state legislatures called special sessions to vote on the amendment and the requisite thirty-six states ratified it. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 1920, making it officially part of the United States Constitution. Despite decades of women’s activism on behalf of suffrage, none of the political officials bothered to invite any women to observe the signing.

Voting Rights and the Nineteenth Amendment

Infringements on the right to vote affected women in communities that faced oppression and limits on suffrage due to literacy, national origin, and other factors. Native people did not gain citizenship rights until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. However, the act did not guarantee the right to vote and many states kept Indigenous people disenfranchised until the 1965 Voting Rights Act. African Americans faced Jim Crow restrictions in the South and those who tried to vote risked racist violence, intimidation, and lynching. From the late nineteenth century to the post-World War II era, Asian exclusion legislation, Supreme Court decisions, and federal policies prohibited Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and other Asian immigrants from citizenship and voting. It took until the McCarran-Walter Nationality Act of 1952 to secure the right to vote for naturalized immigrants from Asia. Literacy tests kept some citizens from voting until 1975 revisions to the Voting Rights Act required that ballots be printed with translations for voters who spoke Spanish or Indigenous and Asian languages. The Nineteenth Amendment removed the restriction of sex but did not enfranchise women if they were subjugated on grounds other than gender.

Even in the twenty-first century, several state governments continue to prevent people from exercising their right to cast a ballot. Such restrictions intersect with inequality of gender, race, class, income, and often affect women. After the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which states that key aspects of the 1965 Voting Rights Act were unconstitutional, many states have revised their requirements for voting. Examples of these requirements include accepting only government-issued photographic identification, restricting easy access to the polls by relocating polling places away from communities of color or by closing them entirely, or by limiting voting hours and days. Many of these restrictions on voting have had a disproportionate impact on women, demonstrating that the need to protect voting rights remains imperative.

Suggested Readings

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Cahill, Cathleen D. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

Florey, Kenneth. Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study. McFarland & Company, 2013, and American Woman Suffrage Postcards: A Study and Catalog. McFarland & Company, 2015.

Hunter Graham, Sara. Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

Goodier, Susan. No Votes for Women: The Anti-Suffrage Movement in New York State. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Goodier, Susan, and Karen Pastorello. Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Gordon, Ann D., ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Against an Aristocracy of Sex, 1866-1873, vol. 2, 6 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

Harrington, Page. Interpreting the Legacy of Women’s Suffrage at Museums and Historic Sites. American Association for State and Local History Series. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021.

Hewett, Nancy, ed. No Permanent Waves: Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Huyck, Heather. Doing Women’s History in Public: A Handbook for Interpretation at Museums and Historic Sites. American Association for State and Local History Series. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020.

Jones, Martha S. Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

Keyssar, Alexander. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Mead, Rebecca. How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868-1914. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850 to 1920. Bloomington: Indiana Press, 1998.

Tetrault, Lisa. “Lessons from the Constitution: Thinking Through the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments,” Social Education 83, no. 6 (November/December 2019): 361-368.

Wagner, Sally Roesch. Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists. Summertown, TN: Native Voices, 2001.

Women and Social Movements Database and the Crowdsourcing Project (which collects women’s suffrage biographies). https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/VOTESforWOMEN.

For a general timeline of the US suffrage movement, see https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/People/Women/Nineteenth_Amendment_Vertical_Timeline.htm.

Author

~ Susan Goodier, PhD, is an assistant professor at SUNY Oneonta where she teaches courses in women’s history and other topics. She authored No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement (University of Illinois, 2013), and co-authored, with Karen Pastorello, Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State (Cornell University, 2017). It won an Award of Excellence from the American Association for State and Local History.