The quest for museums to be diverse and inclusive in staffing, leadership, and programs is not a new challenge. At a recent American Alliance of Museums (AAM) annual meeting, Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, former director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, delivered a landmark keynote that challenged museums “to be of social value by not only inspiring but creating change around one of the most critical issues of our time—the issue of diversity.” Cole’s speech compelled AAM to recognize the need for diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion to ensure that the field remains relevant and sustainable.

In response to the need to be diverse and inclusive, museums, historic sites, and related institutions have written strategic plans that promise to include all voices, cultures, and histories in their board membership, staffing, policies, educational programs, collections, exhibits, and events. Efforts to make museum collections more diverse and inclusive, however, have been slow and problematic. Why? The biggest contributing factor is the lack of diversity within curatorial and collections departments. According to the 2018 Art Museum Staff Demographic Report, produced by the Andrew Mellon Foundation and Ithaka S+R, the number of employed curators who are people of color is 16%, compared to 84% of curators who identify as white. Museums with specific cultural and ethnic collections often do not hire curators, collections managers, or registrars representative of the cultural origins or background of these collections; nor do they establish meaningful relationships with diverse communities.

Throughout my 23-year career in the museum field, I have experienced several occasions where I have had to defend appropriate cultural representation in the areas of object interpretation, documentation, and care. I will endeavor to describe three incidents at various levels within my career where I have had to tackle challenging scenarios around proper cultural representation of difficult objects, overcome personal trauma and emotion associated with racially sensitive objects, and combat discrimination within historical collections. These specific accounts are shared in hopes of motivating my colleagues working in the museum field to be aware of these issues around inclusivity in collections, spark discussion, and speak up in defense of proper cultural representation.

Appropriate Interpretation of Racially Sensitive Collections

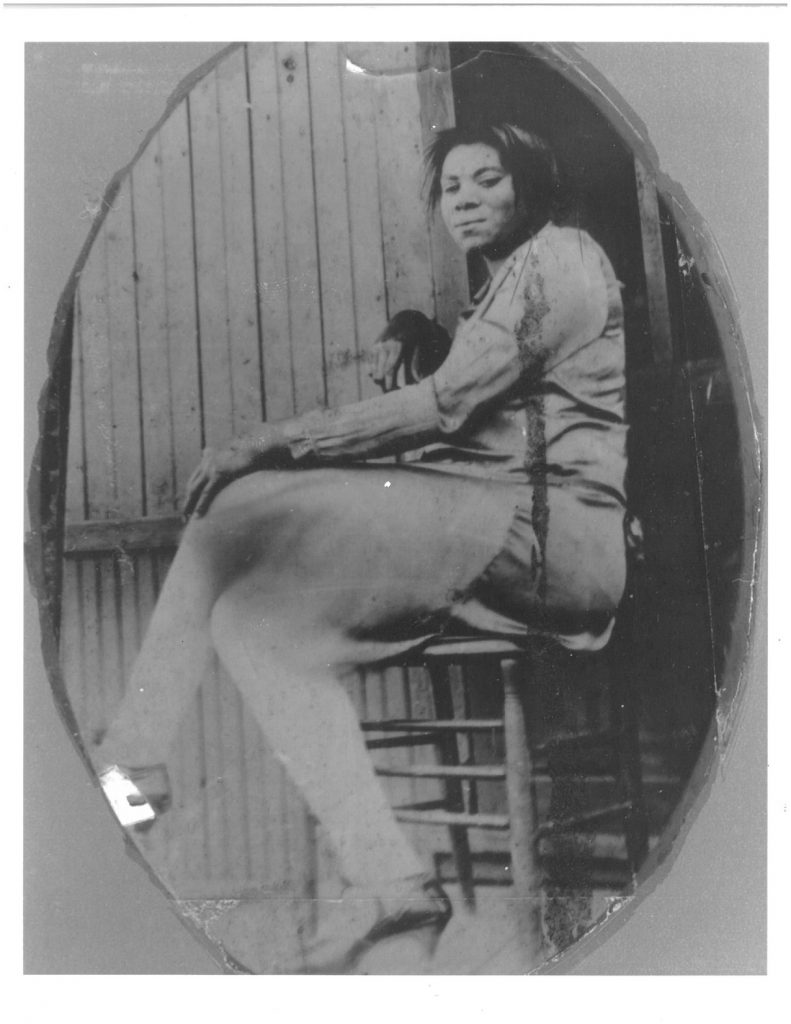

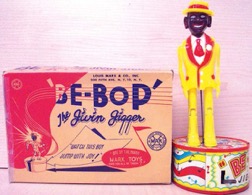

Newly established in my career and armed with the scholarly lessons that earned me my graduate degree in history with a special emphasis in African American history, I thought I was equipped for the curatorial responsibilities neatly outlined in my job description and evaluation. However, there were no university courses or examinations that could have prepared me for the encounter that I had with the chief curator involving the display of racially offensive African American toys that dated from the 1930s and 1940s. The museum didn’t know quite what to do with these toys and how to interpret the sensitive subject of race. Before my arrival, these toys received very little attention and care. They were stored behind different objects as if they didn’t even exist. In fact, the small African American collection that was housed at the museum had been overlooked and no additional funding was allocated to support the growth of this collection. My predecessor was tasked with developing a gallery designed to highlight the history of African Americans and this task left her very little time to grow and care for the collection.

My responsibility as curator of the African American collection was to acquire new objects through loans and purchases as well as interpret and develop exhibit displays that would appeal to the museum’s targeted audience: children. My assistant and I worked with the museum registrars to properly document the collection, including the racially offensive toys. In planning for several upcoming exhibit displays to showcase the African American collection, one of the chief curators asked me to incorporate the racially offensive toys into the exhibits. Because of the sensitivity of the subject matter and the possible lack of understanding by children along with the potential to offend parents, I turned down the initial suggestion, offering several justifiable reasons.

Eager to create a teachable moment for both my colleagues and museum visitors, I provided the chief curator with an alternative way to showcase these toys. I volunteered to develop an interactive program that would allow visitors to learn about the negative stereotypes that were attributed to African Americans and recognize how these toys contributed to prejudices and discrimination that were taught in American popular culture. Because the program would be geared toward children of all ages, I explained that this would be a great teaching moment to demonstrate the importance of respect for all cultures and ethnicities. I was shocked that the chief curator didn’t share my ideas nor was she interested in expounding on the history of negative representations of African Americans. She demanded I place the racially offensive toys in the exhibit displays. Was this really happening? What book or guidelines could I reference to stop this insensitive act? What about all of the meetings that I attended that encouraged me to display African American objects and to develop exhibits that celebrated the historic achievements and culture of African Americans? I can’t remember how many days passed before the chief curator and I discussed again the usage of the racially offensive toys. I do recall that when we spoke, I warned her that this plan to display these toys would shatter the relationship between the museum and the African American community. She responded by telling me “maybe that’s the type of attention we need from the African American community.” Stunned by her answer, I told her that I would not display the toys. The chief curator was secure in her decision. I asked another African American museum colleague for advice and she was prepared to alert the local news stations. My connections with the African American community gave me the support I needed to challenge the chief curator. The museum was spared any unnecessary publicity and the racially offensive toys were not exhibited. Was this a victory, or was I unearthing the reality that some of the curators in this museum were not willing to accept inclusiveness?

Learning Points: As a member of the collections and exhibition departments in your museum, you have a duty to interpret cultural collections truthfully and with respect. Never compromise your integrity due to the pressures of colleagues who may not share the same ethical understanding or responsibilities. Always look for teachable moments to enlighten colleagues and the public when dealing with sensitive materials. I can’t stress enough the importance of building meaningful relationships with communities that are not appropriately represented. Their support and trust will be key to measuring the museum’s goal to become more inclusive.

Receiving and Processing Racially Sensitive Collections

After working in the museum field for over 12 years as a curator and registrar, I considered myself well experienced. I had the awesome opportunity to work at several different museums which allowed me to manage and exhibit a number of diverse collections that represented American culture. My interest and ongoing training in public history gave me the advantage in connecting with local African American communities to help them preserve and interpret their histories. I received invitations from colleges and universities, including historic Black institutions to teach and mentor students about museum careers with a special focus on professions as curators, registrars, and collections managers. I mostly appealed to history students and emphasized the importance of object documentation.

Throughout my career, I have processed hundreds of racially sensitive objects and my ability to identify and research these collections became second nature. I was accustomed to documenting objects that were both uncomfortable to look at and to discuss. I often had to console many donors that were uneasy about having these racially sensitive objects connected to their families and thus many of these donors opted to remain anonymous. However, I never expected that a particular donation would almost hinder my ability to fully document an object.

In routine fashion, I accepted a call from a donor that wanted to remain anonymous. Emotionally distraught, the caller informed me that she had found a post card while cleaning out the home of an elderly relative. She was utterly disgusted to know that the relative had saved this particular item. I assured her that the museum would accept the post card along with any historical information. The caller mentioned that she would enclose it in stationary and mail it right away. She didn’t describe the content of the post card and I didn’t ask. The object arrived within a few days. When I opened the beautiful stationary paper, I was horrified to see a black-and-white post card of four African American men hanging from one tree. I knew that lynching photographs were often sent as post cards, but I had never actually seen one.

The post card was sent with no additional information so I had to examine the photograph carefully to find clues that would reveal the timespan and possible location of the lynching to help me find out more about the African American men that were murdered. It took me weeks to process this post card. I was haunted by the bodies hanging from the trees and the faces of the African American onlookers that were standing nearby. I wanted to pass this to the registrar or slip it into a folder to be processed later, but an upcoming collections committee meeting forced me to complete the documentation. To heal from this emotional trauma, I incorporated the lynching post card in my lectures and workshops to teach other museum professionals how to accept racially sensitive materials.

Learning Points: How do museums prepare their collection staff to handle the uncomfortable emotions of processing racially sensitive collections? How can the community help? I challenge museum professionals to ask these questions. Because museums want collections to be more diverse, there must be an investment to make resources available for collections staff to learn how to work with sensitive materials. I encourage staff to openly discuss with other colleagues and communities that share these difficult histories. Be willing to listen and learn from community or local historians and invite them to help with the documentation of these objects.

Preventing and Advocating against Discrimination in Collections

As a seasoned museum professional in collections, I was comfortable working with various types of cultural objects. Collections care is paramount for all objects donated to or purchased for the museum—at least that is how I was trained, in accordance with AAM collections stewardship policies. As collections manager at a history institution, I worked collaboratively with the museum curator. Our relationship soon became frayed when the curator refused to store a significant Latino Art Collection on the same shelves with framed European paintings. At first I thought the curator had misunderstood my request to rehouse the Latino Collection in the permanent storage area. The reality became clear to me. This was not a mistake. The curator purposely devalued the need to administer equal care to an object simply by its cultural affiliation. This was unbelievable. Apparently, my predecessor had tried unsuccessfully for two years to incorporate the Latino artwork on the shelves of the main collections storage. Instead, the framed art pieces were either hung in various staff workspaces or stacked in the hallway. Was I experiencing firsthand cultural object discrimination?

I immediately alerted my supervisor to this act of subtle racism that was practiced through selective storage of objects based on culture and race. He supported me in my plan to care and store all collection objects equally. With several interns, I moved the entire Latino Art Collection to the designated art storage in the main collections building. It took several weeks before the curator noticed the newly stored artwork on the shelves. She retaliated by trying to get other staff to move the objects out of the main collections building. Her efforts became pointless when I reminded the curator that it is the duty of the museum to care for all collections as stated in our collections management policy.

Learning Points: The degree of object care should not be determined based on cultural affiliation or race. Cultural object discrimination does exist, but in subtle ways. The way to detect this is by asking questions: How and where are cultural objects housed in collections storage? Have they been properly documented and accessioned or are they stored in uncatalogued or unmarked boxes? Do the collections that represent a specific ethnicity or race receive the same financial funds and treatment?

I applaud the museums and institutions that are conscious of the care of their collections on an equal scale regardless of their cultural affiliation, but there are many that do not exercise that level of consciousness. I witnessed this inequality at a history institution several years ago when my interns and I were conducting research for an upcoming online exhibition. The African American collection of rare photographs and documents from World War I needed serious care and treatment. The collection was stored in worn archival folders and boxes. I was shocked that the institution allowed us to physically handle the photographs because of their fragility. When I asked the assistant if this collection would be digitized soon to prevent unnecessary handling, she told me that was their hope, but there were no definite future plans. Sadly, the donors gave these priceless photographs and papers of their military service with the museum’s promise that their items would receive the best quality of care.

Collections managers, conservators, and curators should feel empowered to speak up for the care of all collections. Don’t be afraid to correct colleagues. Challenge leadership to allocate appropriate funds to treat and document objects, particularly the ones that have a significant connection with local communities that are not represented in the museum.

Defending cultural representation in the areas of object interpretation, documentation, and care takes courage and a lot of patience. I credit my friends, mentors, and fellow colleagues for giving me direction and advice to speak out and educate colleagues and leadership on the importance of diversity and inclusion. I hope these examples will alert my colleagues of cultural exclusivity “red flags” within collections, generate meaningful conversations, and encourage individuals within the profession to take action where needed.

Suggested Readings

American Alliance of Museums, Facing Change: Insights from the American Alliance of Museums’ Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion Working Group, 2018, https: //www.aam-us.org/programs/diversity-equity-accessibility-and-inclusion/.

Schonfeld, Roger C., Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, January 28, 2019, https://mellon.org/resources/news/articles/art-museum-staff-demographic-survey-2018/.

Author

~ Marian Carpenter has over twenty years of experience in collections management and exhibitions. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in History and Afro-American Studies from Indiana University and a Masters of Arts in American History with a concentration in African American History from the University of Cincinnati. Currently, she is the Associate Director of Collections/Chief Registrar at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art.