Urban renewal is the process of seizing and demolishing large swaths of private and public property for the purpose of modernizing and improving aging infrastructure. Between 1949 and 1974, the U.S. government underwrote this process through a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grant and loan program. Although the money was federal, renewal plans originated with and were implemented at the local level.

In cities nationwide, the consequences of urban renewal included the destruction of historic structures, the displacement of low-income families, and the removal (often closure) of small businesses.[i] The local officials and business leaders who promoted renewal regarded the federal program as the best available method for addressing the problems attendant with suburbanization, a process fueled by HUD and G.I. Bill mortgages. For many black, Latinx, and low-income families, however, it was a tragedy and injustice, a loss of home and community. Urban renewal reshaped the geography and demographics of cities, and, in the process, exacerbated conflict and promoted resistance.

Federal Policy and Local Politics

Although some renewal projects, such as Stuyvesant Town in New York City, predated the Housing Act of 1949, this law, along with later iterations, effectively expanded the practice to cities across the nation. With the goal of improving the nation’s housing stock and reviving its cities, the federal urban renewal program provided grants and loans to municipalities, underwriting much of the cost of site acquisition and clearance. The program was attractive to city leaders both because it provided what appeared to be an answer to declining tax revenue and because the federal government defrayed two-thirds (three-quarters in smaller places) of the cost. The city’s share could be paid from state funds or through credits for capital projects, such as school construction or sewer-line improvements. Clearance completed, cities were responsible for transferring the parcels to private developers or public agencies for reconstruction.

Initially, support for the federal urban renewal program united business interests and housing reformers, conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Ultimately, however, commercial development proved more attractive than low- and middle-income housing to most city leaders.[ii] These same officials would use urban renewal funds to destroy much of their city’s stock of affordable housing.

Over the course of the program’s life, federal officials approved over $13 billion in grants to more than 1,200 cities, ranging in population size from a few thousand to several million. Although there is no precise count of persons displaced or structures demolished, we do know that hundreds of thousands of families lost their homes to urban renewal. State and federal highway construction displaced hundreds of thousands more.[iii]

By the late 1960s, the federal urban renewal program had become controversial, both for its destructiveness and for the slow pace of reconstruction. In 1968, for example, the National Commission on Urban Problems found that the application process alone took, on average, four and one-third years to complete. Even worse, of 37,200 acres cleared between 1949 and 1967, only 17,400 had been, or were in the process of being, redeveloped.[iv] In 1974, in the midst of a recession, federal funding for renewal was reduced and folded into the Community Development Block Grant program.

Memory and Archives

Due, in part, to federal reporting requirements, the local story of urban renewal tends to be well documented in municipal and county archives. Of course, documents in government archives typically preserve the redeveloper’s perspective, giving little voice to the people who would lose their homes and businesses. Indeed, an over-reliance on archival records such as these has produced a scholarly literature too focused on the work and worldview of planners and politicians. Nevertheless, historians searching among the records of their local urban renewal agency will likely uncover the seeds of a social history of lost neighborhoods and missing places.

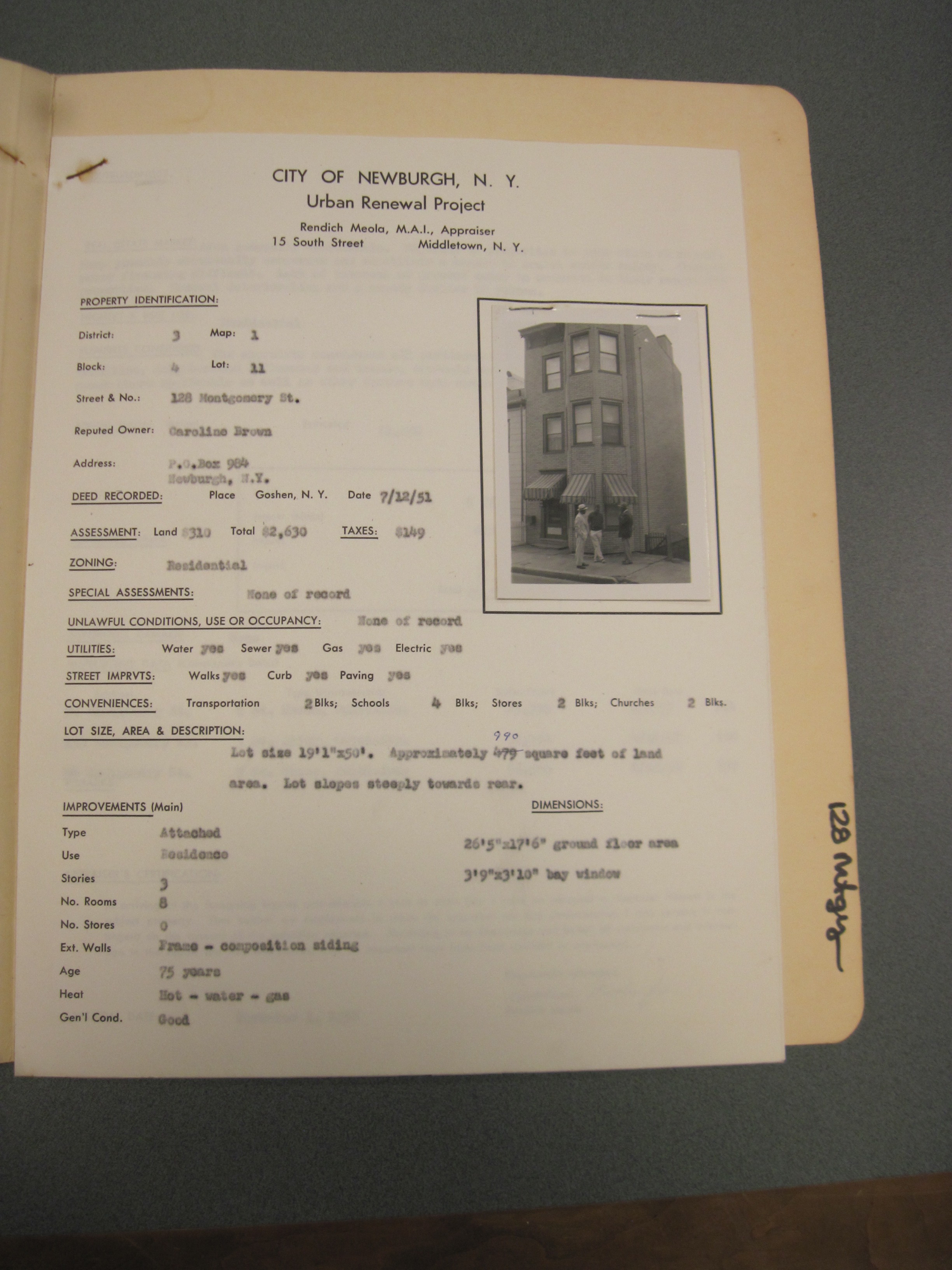

For the purpose of inclusion, perhaps the most important of these official records are photographs, especially pre-demolition images of the redevelopment area. Although produced for appraisal purposes or in response to litigation over reimbursement payments, these photographs preserve lost architecture, commerce, and street life. (See, for example, Finding Kenyon Barr: Exploring Photographs of Cincinnati’s Lost Lower West End.) Some photographs may even reproduce the interiors of public buildings and private homes. These interior photographs are particularly valuable when relocation records are unavailable. In the case of Albany, New York’s Empire State Plaza, for example, images of rooming house interiors provide a rare window into the lives of the many roomers who once made their home in the redevelopment area. The members of this transient group are largely undocumented by other archival sources and have been forgotten by most of the area’s former residents.

In our research on Albany (98 Acres in Albany), pre-demolition photographs have proved to be important outreach tools. Promoted on social media and in public presentations, these images have helped us both build an audience and, more importantly, identify potential informants among the residents and business owners who once populated redevelopment areas. Furthermore, these photographs provide something of value to share with our informants. Focused as they are on the details and condition of soon-to-be-demolished structures, they differ dramatically from family photographs and often have the effect of prompting memories, some happy, others painful.

In conversations with former residents, researchers should expect to uncover stories of emotional and economic hardship—an aged father who fell into depression after closing the family store, a divorced or widowed mother who struggled with alcohol after losing her rooming house. (Most rooming houses were woman-owned businesses.) Even those who did not suffer economic hardship are likely to have experienced a painful loss of place and community. Psychologist Marc Fried and psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove have analyzed the emotional impact of urban renewal. In 1963, Fried, who studied former residents of Boston’s predominantly white West End, described being forcibly dispersed as “highly disturbing and disruptive,” the emotional response as akin to grief. “It’s just like a plant,” one of his informants told him, “when you tear up the roots, it dies!” More recently, Fullilove diagnosed the trauma of displacement as “root shock.” Focusing on neighborhoods where southern migrants settled during the Great Migration, Fullilove blames urban renewal for the loss of “kindness” and cohesiveness that served as a “buffer” against personal sorrows and external prejudice. At the individual level, root shock is “a profound emotional upheaval” that “undermines trust, increases anxiety…, destabilizes relationships, destroys social, emotional, and financial resources, and increases the risk for every kind of stress-related disease, from depression to heart attack.”[v]

One challenge of collecting such emotionally charged memories is to recognize how nostalgia and anger may color them. For example, the children of former business owners and homeowners typically underestimate the value of reimbursements paid for seized property. This error of fact, nevertheless, contains an important kernel of truth, both emotional and economic. With justice, these informants feel unfairly dispossessed. Furthermore, due to redlining, buildings demolished for renewal were typically undervalued compared to similar structures in other parts of the city.[vi]

Citywide Disruption

Other stressors were felt citywide. In Albany, for example, the destruction of 3,300 housing units and displacement of roughly 7,000 residents produced a crisis of low-income housing, especially in the city’s overcrowded black ghettoes. A related problem was the lack of affordable housing for the elderly poor, who had previously found shelter in the urban renewal area’s rooming houses and single-room-occupancy hotels. The noise, dirt, and disruptions of demolition and reconstruction reverberated across the city. Conditions were worse in the areas adjacent to the redevelopment area and along the route from the construction site to the dump.

Urban renewal destroyed not just homes but also community institutions, including churches, schools, and ethnic and fraternal organizations. Some neighborhood bars served important social functions, by organizing bowling leagues, for example. Others quietly catered to LGBTQ patrons. In San Francisco, Damon Scott found that city leaders’ efforts to shut down such bars via urban renewal prompted the gay community to organize in the mid-1960s. Researchers in other cities are likely to find evidence of LGBTQ sociability—as well as of sex work and gambling—in taverns targeted for clearance.[vii]

Resistance

Urban renewal is not simply a story of trauma but also of community building, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, an era of civil rights organizing and urban revolts. By this time, many city residents had experienced the losses and disruptions of earlier projects and were wary of redevelopers’ promises. Local officials, likewise, had grown weary of construction expenses and delays; they were increasingly willing to listen to protesters. In Boston, for example, community activists successfully halted construction on the Southwest Expressway, convincing local officials instead to invest in mass transit improvements. In New York City, Jane Jacobs and her Greenwich Village neighbors led the most famous of such protests, against Robert Moses’s proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway.

Urban renewal’s threat to homes and neighborhoods sparked demands for social justice. In the West Town section of Chicago, for example, twenty-two Catholic parishes collaborated with Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation to form the Northwest Community Organization. The organization successfully resisted redevelopment by bringing community members together behind a “People’s Conservation Plan,” which emphasized rehabilitation, rather than demolition, and preservation of the area’s economic and demographic character. Community leaders initially used this plan as a rationale to block City redevelopment proposals and, later, to negotiate a “Program for Improvement” with business leaders who sought to revitalize Chicago’s core. Similar organizations were founded in cities across the nation, and although they might not have left papers behind, it is likely that the local press covered their stories and that former activists would be willing to be interviewed.

As a whole, the opposition to urban renewal was motivated by a commitment to protect both low-income communities and architecturally significant structures. Although the social justice and preservation strands of opposition were not necessarily united in their priorities, groups representing each strand did form alliances toward shared goals. In Albany, for example, a woman’s civic club, two homeowner’s associations, and the NAACP banded together to stop construction of a new arterial highway in 1968. Their priorities were, respectively, protecting a downtown park, preventing demolition of historic homes, and preserving access between low- and middle-income neighborhoods.

Reconstruction

In most but not all places, urban renewal is also the story of reconstruction. Modern housing complexes, shopping malls, office buildings, civic centers, sports arenas, parking lots, and college campuses all owe their existence to urban renewal. Funded through private investment and public bonds, erecting these new structures required the skill and labor of countless workers. Many of these men and their families remember this period as an era of economic security. Try contacting local labor federations or building councils. Be warned that because urban renewal has become controversial, these potential informants may be skeptical of your motives. Then again, you may find they are proud of their work.

The long history of black exclusion from the construction unions means that most of the tradesmen you meet will be white. Look for information on apprenticeship programs designed to address African American demands for equal access to jobs. Most of these programs failed to live up to the demands. As a result, you will likely find evidence of activism and protest.[viii]

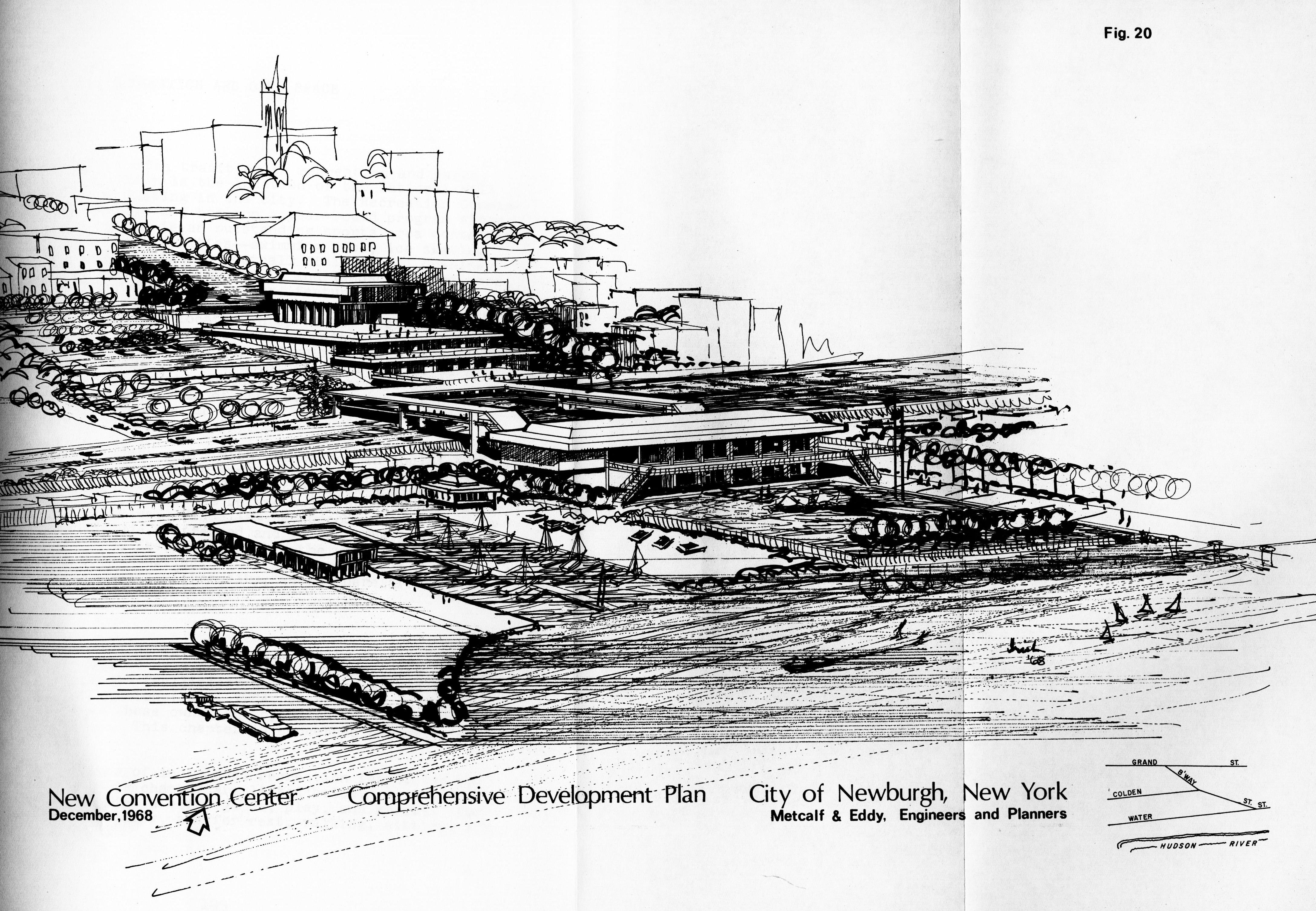

Local planners, architects, and bureaucrats generated a great deal of documentation. Planning studies, architectural renderings, meeting minutes, and other related correspondence can be found in city and county archives, likely filed among housing authority, planning board, or urban renewal agency records. Together, these documents and drawings present a vision of a prosperous and populous future that the relevant projects seldom realized. They may also record how plans changed over time in response to changing conditions. (The process of applying for and receiving federal funds typically took four or more years, site clearance and reconstruction much longer.) Like construction workers, planners and architects may be reluctant to share their experiences, but their perspective is important for understanding how local leaders hoped to transform their city. Keep in mind that their intent was to improve urban environments, even if the results fell short of their goals.

Idealistic elements of planning and design deserve serious consideration. In New York State, for example, the goal of racial and economic integration drove the work of Edward J. Logue and his staff at the Urban Development Corporation. This state agency was formed in 1968 to address a flaw in federal policy—the overabundance of unproductive land cleared with renewal funds. Over the course of the next seven years, the UDC coordinated the funding and construction of almost 31,000 housing units in 42 New York towns and cities. Resistance to integration, combined with the recession of 1973-1975, led to the UDC’s premature demise.

Lasting Impact

The results of renewal are varied. In some places, private developers built convention centers, shopping malls, office towers, and luxury apartment buildings on the remains of communities condemned as blighted. In other cities, local housing authorities erected new low-income public housing complexes, where displaced families were given priority over other potential tenants. All of this served to intensify the racial and economic divisions that still exist in most, if not all, American cities.

At its worst, urban renewal was simply destructive. When interest rates rose and federal funding dried up in the mid-1970s, demolition halted along with reconstruction. Cities like Newburgh, NY, Atlantic City, NJ, and even New York City were left with empty fields or parking lots where neighborhoods once stood.

Since the mid-1970s, rehabilitation, rather than demolition, has become the preferred method of revitalizing historic downtown business and residential districts. As part of a process of gentrification, this strategy has successfully lured wealthy whites from the suburbs back to the city. At the same time, this new wave of redevelopment has displaced low-income minority communities. Compared to urban renewal, gentrification is a more varied and diffuse process and has thus far proved harder to fight.[ix]

Notes

[i] See Digital Scholarship Lab’s “Renewing Inequality,” part of the American Panorama series, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram&text=sources.

[ii] For more on the politics of urban renewal, see Roger Biles, The Fate of Cities: Urban America and the Federal Government, 1945-2000 (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2011) and Jon C. Teaford, The Rough Road to Renaissance: Urban Revitalization in America, 1940-1985 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

[iii] The National Commission on Urban Problems estimated that by 1967, federally funded urban renewal projects were responsible for the demolition of 404,000 dwelling units. Eleven years of highway construction, 1956-1967, led to the displacement roughly 330,000 urban households. National Commission on Urban Problems, Building America’s Cities (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1969), 81.

[iv] Ibid., 165-69.

[v] Marc Fried, “Grieving for a Lost Home: Psychological Costs of Relocation” in James Q. Wilson, ed., Urban Renewal: the Record and the Controversy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966), 359-60. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It (New York: One World, 2004), 14, 122-23.

[vi] Redlining was the informal term given to the practice by banks and other home mortgage lenders of denying loans in inner-city neighborhoods deemed risky due to the presence of immigrants and people of color. For more on redlining, see Digital Scholarship Lab’s “Mapping Inequality,” part of the American Panorama series, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58.

[vii] Damon John Scott, “The City Aroused: Sexual Politics and the Transformation of San Francisco’s Urban Landscape, 1943-1964,” Ph.D. diss., University of Texas, Austin, 2008.

[viii] See Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry, edited by David Goldberg and Trevor Griffey (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010).

[ix] See “Cities for People, Not for Profit!” http://citiesforppl.org/.

Suggested Readings

American Association for State and Local History. “Conference Context: White Flight and Civil Rights in Johnson County, Kansas.” AASLH Blog. https://aaslh.org/conference-context-white-flight-and-civil-rights-in-johnson-county-kansas/.

Aylworth, Stephanie. “A Multifaceted Approach to Historic District Interpretation in Georgia.” The Public Historian 32, no. 4 (2010): 42-50. doi:10.1525/tph.2010.32.4.42.

Baumann, Timothy, Andrew Hurley, Valerie Altizer, and Victoria Love. “Interpreting Uncomfortable History at the Scott Joplin House State Historic Site in St. Louis, Missouri.” The Public Historian 33, no. 2 (2011): 37-66. doi:10.1525/tph.2011.33.2.37.

Bendiner-Viani, Gabrielle. Contested City: Art and Public History at New York’s Seward Park Urban Renewal Area. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019.

Cohen, Lizabeth. Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019.

Crockett, Karilyn. People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018.

Frieden, Bernard J., and Lynne B. Sagalyn. Downtown Inc.: How America Rebuilds Cities. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991.

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted out Cities. New York: New Village Press, 2013.

Hurley, Andrew. Beyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner Cities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

Lost Rondout: A Story of Urban Removal (film). Directed by Stephen Blauweiss and Lynn Woods. Kingston, NY: Lost Rondout Project, 2016.

Mirabal, Nancy Raquel. “Geographies of Displacement: Latina/os, Oral History, and The Politics of Gentrification in San Francisco’s Mission District.” The Public Historian 31, no. 2 (2009): 7-31. doi:10.1525/tph.2009.31.2.7.

The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (film). Directed by Chad Freidrichs. Columbia, Missouri: Unicorn Stencil Documentary Films, 2011.

Rae, Douglas. City: Urbanism and Its End. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Rotenstein, David. “Historic Preservation Shines a Light on a Dark Past.” History@Work blog. https://ncph.org/history-at-work/historic-preservation-shines-a-light/.

Zenzen, Joan. Fort Stanwix National Monument: Reconstructing the Past and Partnering for the Future. Albany: SUNY Press, 2008.

Zipp, Samuel. Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Authors

~ Ann Pfau, David Hochfelder, and Stacy Sewell are the 98 Acres in Albany project. They blog about the history of urban renewal at https://98acresinalbany.wordpress.com/. They were recently awarded two National Endowment for the Humanities grants to plan and begin prototyping a website tentatively titled Picturing Urban Renewal. Pfau is an independent scholar. Hochfelder is associate professor of history at the University at Albany, SUNY. Sewell is professor of history at St. Thomas Aquinas College.