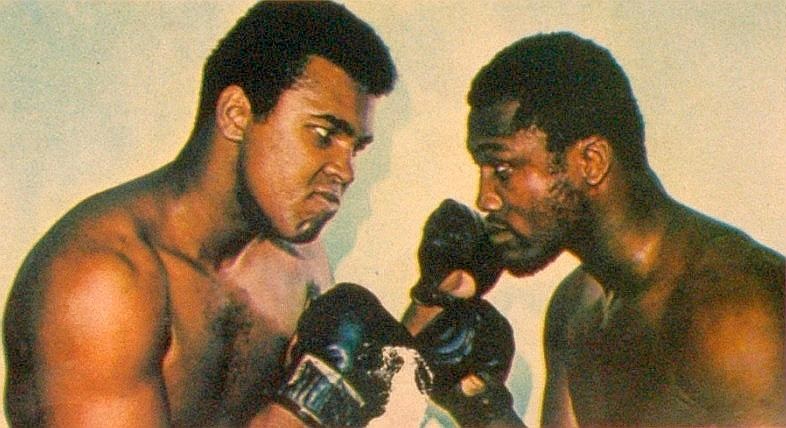

Visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., come face to face with a vast array of iconic objects from America’s past, including a pair of Muhammad Ali’s boxing gloves, the light bulb Thomas Edison used when he first publicly displayed his invention in 1879, and the inaugural gown worn by First Lady Michelle Obama in 2013.[i] These things—boxing gloves, a light bulb, and a gown—belong to the category known as material culture, what the folklorist Henry Glassie described as the “tangible yield of human conduct” and the historian Leora Auslander called “the class of all human-made objects.”[ii]

People throughout history have had a complex relationship with the objects they create, use, live with, sell, discard, and treasure. Although human beings by definition create material culture, they cannot control how objects are used or the meanings that come to be associated with them. For historians, objects have many stories to tell: there is the story of an object’s invention and creation; stories about an object’s useful life (who acquired it and for what purposes it was put to use); and stories of what we might think of as its “afterlife,” when an object is taken out of circulation to become a part of an institutional collection where it becomes available for historians to study. Collecting a wide range of objects and uncovering as many of these stories as possible can help create a more inclusive understanding of the past.

Historians’ Use of Material Culture

Historians have not always invested significantly in studying material culture. Earlier generations of historians concentrated largely on politics, war, and economics, predominantly relying on written primary sources, mostly created by elites (and often elite men) who had the time and resources to create a documentary record. Collectors and curators at museums and historic sites were often similarly focused on collecting and displaying what had been owned by the elite.[iii] These curators devoted themselves to questions of provenance and connoisseurship, which focused on the artists and craftspeople who had made the objects and on the museum’s acquisition of the finest examples of specific types of decorative arts, often furniture and ceramics, to build these elite-focused collections. The social historians who rose to prominence in the field beginning in the second half of the twentieth century built on the work of a relatively small group of pioneering scholars and curators who had long been interested in telling the stories of non-elites. Beginning in the 1960s, widespread attention became focused on the past lives of ordinary men, women, and children.[iv] Because they did not usually leave as rich a written record as the wealthy did, their lives had to be explored by other means. The material world contained many objects that could help to reconstruct and tell their life stories. Material culture began to play a much more significant role in the work of this later generation of scholars who sought to better understand the lives of non-elite men and women.

Historians who study the material world undertake creative and interdisciplinary work as they engage with historical archaeologists, anthropologists, curators, museum collections, and written sources (including probate records, store accounts, and catalogs) that help us better understand material culture. Collections of everyday items can serve as valuable repositories of information about the lives of the ordinary men, women, and children who inhabited the past and help modern-day museumgoers connect to their stories.

Witnessing Objects

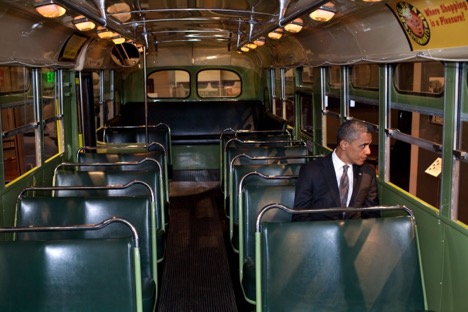

Many historians and public history institutions today rely heavily on material culture to tell compelling stories and engage visitors. One common kind of object collected by museums is the witnessing object. These objects were present at a pivotal moment in the past and serve as tangible links to that history. Being in the presence of one of these witnessing objects enables modern-day people to feel connected to a specific moment or event in the timeline of history. In April 2012, for example, when President Barack Obama visited the Henry Ford Museum, in Dearborn, Michigan, he took the opportunity to sit on the bus where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, the event that sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. Seated on the bus, peering out one of its windows, President Obama physically occupied the space and could imagine seeing through the eyes of leaders and participants in the U.S. civil rights movement.

The ability of material culture to connect visitors to the lives of those who left little evidence in the written record has led museums to seek out new kinds of witnessing objects. In advance of the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Lonnie Bunch, the museum’s director, sought out material evidence, for example, from the Middle Passage—the horrific journey across the Atlantic that brought more than 12.5 million captive Africans to North and South America. What the Slave Wrecks Project ultimately found was the wreck of São José Paquete de Africa, a ship headed to Brazil, which sank in December 1794 off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. The more than 200 men, women, and children who perished in this single tragedy were forgotten until the ship’s discovery in 2010. Despite the thousands of slave ship voyages, this wreckage was the first ever recovered from a ship that sank while carrying captive Africans to the Americas. The ship is a material remnant frozen in time at a moment when it was a tool of the slave trade. Iron ballast, which weighed down the ship for its voyage because human cargo was lighter than the material goods ships like these often carried, was part of what was found at the wreck of the São José. At the Smithsonian, these ballasts stand as witnesses to the horrors of enslavement. As Lonnie Bunch explains, the exhibition of the material remains of the São José are displayed in a reverential “memorial space.”[v]

Multiple Contexts

But to stop there—to let objects only speak for themselves as witnesses to important moments in the past—greatly limits the interpretive potential of material culture. Even objects associated with famous events and people often began life as unremarkable material things. Material culture objects are embedded in multiple contexts—their production, their use, and their “afterlife” as objects of display—from which we can learn a great deal more than their association with past events and people. Furthermore, many scholars who study material culture argue that material culture does more than reflect historical processes; it can also shape them. Of the objects we have already considered, we can also ask: Who made them? What kind of employment practices did these laborers work under? What can we learn about wider social dynamics from these objects? What did these objects mean to the people who owned and used them? In what ways did these objects shape individual and collective identity? What could we learn, for example, about who made Muhammad Ali’s boxing gloves? How did Thomas Edison’s invention change how people lived and worked? What does it say about our gendered understandings of the U.S. presidency that we collect and display the inaugural gowns of the First Ladies? Current-day museumgoers can be challenged to think about how material culture reflected and shaped human identity in the past and at the same time be given opportunities to make connections to their own relationships with the material world.

How to Analyze Material Culture

To understand material culture, people must study the object itself, as well as interrogate a wide variety of other sources. These additional sources—documents, oral histories, other material goods—allow us to develop a more complete picture of the many meanings of material culture.[vi] Without these other avenues of information and understanding, the complex past meanings of the material world would remain largely obscured. Scholars have developed guidelines to assist researchers interested in doing this kind of multi-level analysis of objects. Material culture scholar Karen Harvey has developed a beginner’s approach to fully interrogate an object, which includes three steps. The first step is to develop a physical description of the object. If at all possible, get into the same room as one of the objects and, if it is small enough (and accessible), hold it in your hands. Then describe the object by considering “what the object is made of, how it was made and (of course) when; production methods and manufacture, materials, size, weight, design, style, decoration and date.” The second step is to “place the object in historical context, primarily by referring to other evidence. Here we can explore who owned this (or similar) object, when, and what they were used for.” In this step, the focus is on how the object was used and by whom during a particular time period. In the final step, an even broader view is taken to begin exploring what the object meant in that time period. Placing the object into this “socio-cultural context” enables a deeper understanding of the significance of the object in people’s lives.[vii] To add a fourth step, you could also consider the history of the object once it moved into a museum collection, considering when it was displayed and why.

One such object whose meanings were uncovered only through the interrogation of a wide variety of sources are the foil milk caps from Polk’s Dairy in Indianapolis, Indiana. Historical archaeologist Paul Mullins has studied the city’s historically African American neighborhoods, where a frequently recovered item is a foil milk cap, an item used to close glass milk bottles in the early decades of the twentieth century. At first, researchers set them aside because they appeared to reveal little more than the fact that the occupants drank milk. But as Mullins recounts, an elder of Indianapolis’ African American community later told them how the city’s Riverside Amusement Park, open only to whites, allowed African American admissions one day each year. Foil milk caps were the required admission token, and African Americans in the city called it “Milk Cap Day.” The example of the Indianapolis foil milk caps shows how objects of the material world reflect the larger historical processes in which they are embedded—in this case racism and segregation in the mid-twentieth-century United States—and how even these ephemeral pieces of material culture took on new layers of meaning and could provide more inclusive interpretive possibilities.[viii]

Notes

[i] This entry is adapted, with permission from Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, from Cherstin M. Lyon, Elizabeth M. Nix, and Rebecca K. Shrum, Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers/AASLH, 2017), 98-101, 109.

[ii] Henry Glassie, Material Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 41; Leora Auslander, “Beyond Words,” American Historical Review 110, no. 4 (2005): 1015.

[iii] Gary Kulik traces the development of history museum exhibitions in “Designing the Past: History-Museum Exhibitions from Peale to the Present,” Warren Leon and Roy Rosenzweig, eds., History Museums in the United States: A Critical Assessment (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 2-37.

[iv] See Ellen Fitzpatrick, History’s Memory: Writing America’s Past, 1880-1980 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002) and Briann G. Greenfield, Out of the Attic: Inventing Antiques in Twentieth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), 167-204.

[v] Roger Catlin, “Smithsonian to Receive Artifacts from Sunken 18th-Century Slave Ship,” Smithsonian, May 31, 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/sunken-18th-century-slave-ship-found-south-africa-180955458/.

[vi] As an example of this kind of material culture scholarship, see Rebecca K. Shrum, “Selling Mr. Coffee: Design, Gender, and the Branding of a Kitchen Appliance,” Winterthur Portfolio 46, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 271-298. https://doi.org/10.1086/669669

[vii] Karen Harvey, History and Material Culture: A Student’s Guide to Approaching Alternative Sources (New York: Routledge, 2009), 1-23. One of the earliest sets of guidelines, and one that has been very influential, is Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 1 (Spring 1982): 1-19.

[viii] Paul R. Mullins, “Racializing the Commonplace Landscape: An Archaeology of Urban Renewal Along the Color line,” World Archaeology 28, no. 1 (2006): 60-71.

Suggested Readings

Harvey, Karen. History and Material Culture: A Student’s Guide to Approaching Alternative Sources. New York: Routledge Press, 2009.

Katz-Hyman, Martha B., and Kym S. Rice, eds. World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States. 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO/Greenwood, 2011.

Lubar, Steven. Inside the Lost Museum: Curating Past and Present. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017.

“Twenty Questions to Ask an Object.” From the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Studies Association, Material Culture Caucus.

Winterthur Portfolio. The leading American journal of material culture studies.

Author

~ Rebecca Shrum is Associate Professor of History, Associate Director of the Public History program, and Adjunct Affiliated Faculty, Museum Studies at IUPUI.