Historic preservation is often linked, hand in hand, with ideas of placemaking, where preservationists embed their work in a neighborhood, community, or landscape to highlight what makes that place unique and preserve its character.[i] In doing this work, preservationists make evaluations about a place’s beauty, integrity, and significance. In the United States, the criteria on which they base these determinations come largely from the standards listed in the National Register of Historic Places’ nomination process. As the work of historic preservation has evolved in recent years, however, many practitioners have begun to push back against these limited criteria. More people are looking to tell the stories of underrepresented communities, document and protect vernacular architecture, preserve sites of the recent past, and promote the protection of intangible heritage.

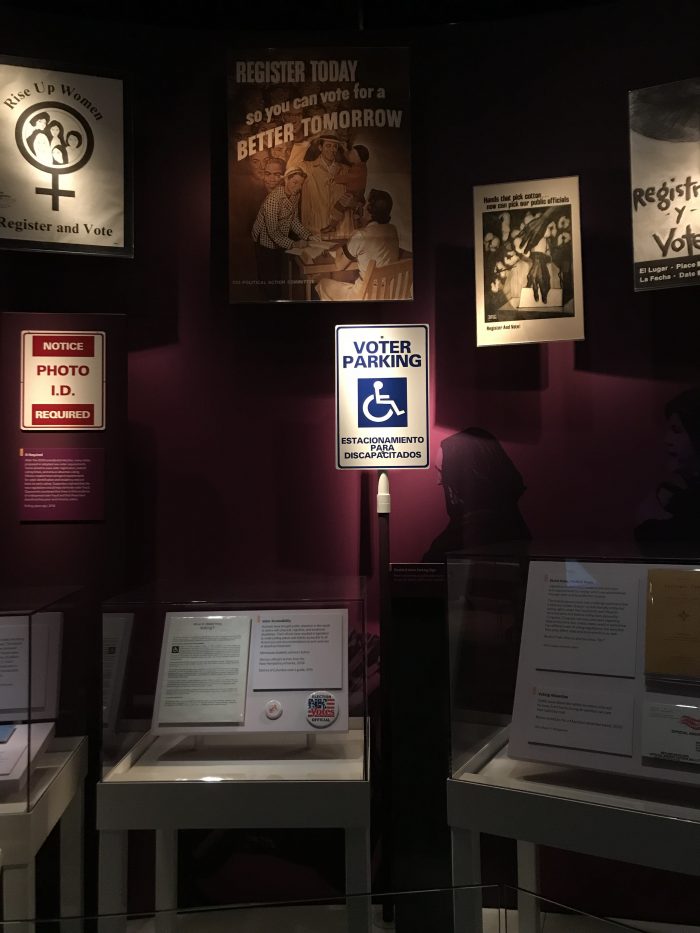

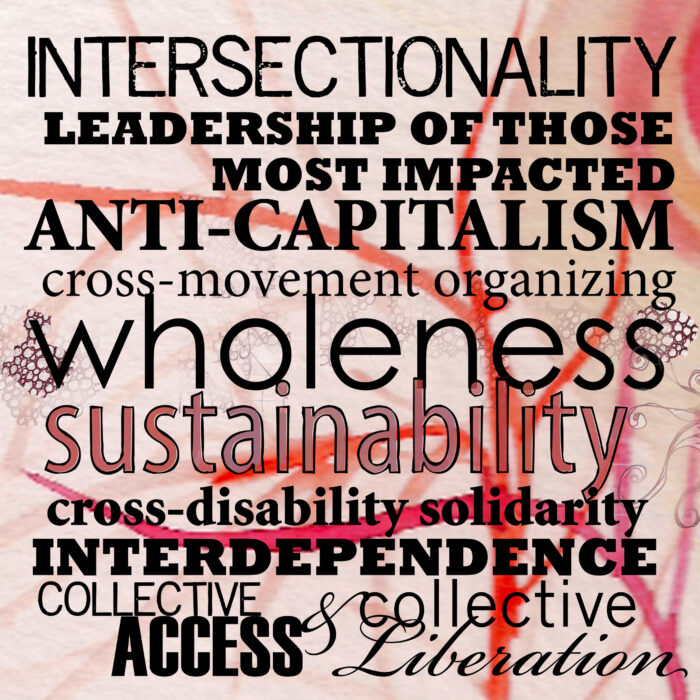

More than fifty years after the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in the United States, more individuals and institutions are recognizing the need to go beyond preserving big houses and places that match traditional standards of architectural beauty. This call to action is pushing the historic preservation movement to embrace inclusive practice—one that not only focuses on the protection of buildings, but also on documenting and sharing the richly varied stories that define places. The goal is to forge a people-centered preservation movement that is inclusive, community driven, and intersectional in nature.[ii]

Early History of the Preservation Movement

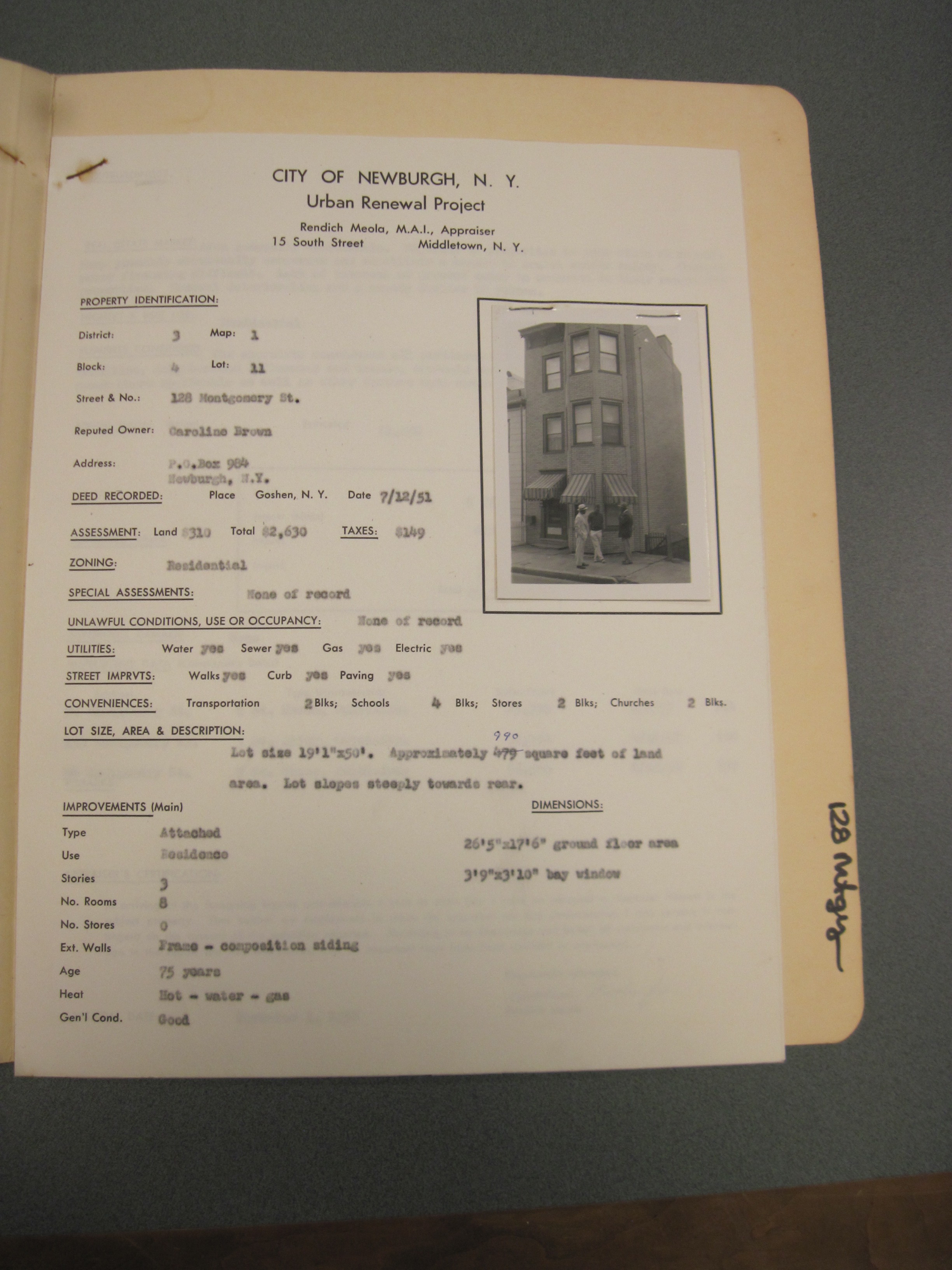

There are two events that are often cited as critical to the founding of historic preservation as a movement in the United States. The first is the story of Ann Pamela Cunningham, founder of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, who rallied women from across the United States in the 1850s to advocate for the protection and preservation of George Washington’s home. The first call of its kind, it opened conversations about preserving and protecting key sites critical to the history of the United States. The second event, taking place just over a century later, was the loss of the magnificent Pennsylvania Railroad Station in New York City. The destruction of this structure spurred those working in the nascent field to come together, leading eventually to the passage of the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). The NHPA, which included the creation of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places, enabled the development of a regulatory process for the protection of historic places.[iii]

Much of the NHPA’s framework came from a report called With Heritage So Rich. Developed by the Special Committee on Historic Preservation within the U.S. Conference of Mayors, this report ended with a series of recommendations and this statement: “In sum, if we wish to have a future with greater meaning, we must concern ourselves not only with the historic highlights, but we must be concerned with the total heritage of the nation and all that is worth preserving from our past as a living part of the present.”[iv] Although the preservation movement has struggled to realize this ambitious vision, contemporary practitioners have embraced a renewed call for broader and more diverse understandings of preservation and its role in society. Significant challenges exist, however, for those who seek to reorient preservation practice.

Focusing on People

A key element of inclusive preservation practice is the need to shift from an exclusive focus on the places being protected to the people who have lived and continue to live in those places. We must also pay more attention to the impacts of preservation projects on neighborhoods and communities.

In an anthology marking the 50th anniversary of the NHPA, former National Trust for Historic Preservation Chief Preservation Officer David J. Brown stated: “To build a movement for all Americans, we must recognize that preservation takes many more forms . . . than the ones associated with our work today. Frankly we need tools that give every person a voice in determining what is worth preserving in their community.”[v] In the same article, Brown emphasizes the need to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach toward a more nuanced understanding of how to work collaboratively with communities to determine what places to protect.[vi]

Leading up to the anniversary of the NHPA, the National Trust for Historic Preservation held a series of listening sessions across the country. These sessions included individuals who were active in the preservation profession as well as voices from outside the field. These conversations coalesced into a vision for the future of preservation. The report, Preservation for People, centers around three different principles:

- A people-centered preservation movement hears, understands, and honors the full diversity of the ever-evolving American story.

- A people-centered preservation movement creates and nurtures more equitable, healthy, resilient, vibrant, and sustainable communities.

- A people-centered preservation movement collaborates with new and existing partners to address fundamental social issues and make the world better.

Preservation for People seeks to lay out strategies and tactics to make preservation more democratic, inclusive, and equitable. Essential to achieving these goals is building a more inclusive profession. Historically, preservation has been seen as an elitist practice, and while the demographics of the field are slowly shifting, there are still significant barriers to entry.

It is critical to demonstrate to young people that preservation is something that is relevant to their lives. During the 2015 PastForward Diversity Summit Jose Antonio Tijerino, president and CEO of the Hispanic Heritage Foundation, stated that “the first step is reaching out. And also making it relevant. How is it relevant to a young black man? Woman? A young Latino? Young Asian? Young LGBT? To be able to feel connected to what your mission is . . .”[vii]

Some organizations have made telling underrepresented stories and protecting places that are sharing these narratives central to their work. For example, Asian Pacific Americans in Historic Preservation and Latinos in Heritage Conservation (LHC) have worked to support a network of individuals who are engaged in these types of projects. Sarah Zenaida Gould of LHC says that “We envision this network as one that equally welcomes professional preservationists and community preservationists. For we all have knowledge, ideas, experiences, and strategies to share.”[viii]

In summarizing the 2015 Diversity Summit which took place at PastForward, Stephanie K. Meeks, then CEO and President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, stated:

Over the course of the discussion, common themes emerged. All of the panelists agreed that recognizing and honoring diverse stories was key to understanding our present political debates and to building a more inclusive and allied future. All felt that, while we have made important strides as a movement, we still have a lot of work to do to get this right. All believed that forging stronger partnerships with and across diverse groups was essential for continued success. And all emphasized the wisdom of today’s broader vision of preservation, in which we seek to save the modest and even ordinary places where history happened.[ix]

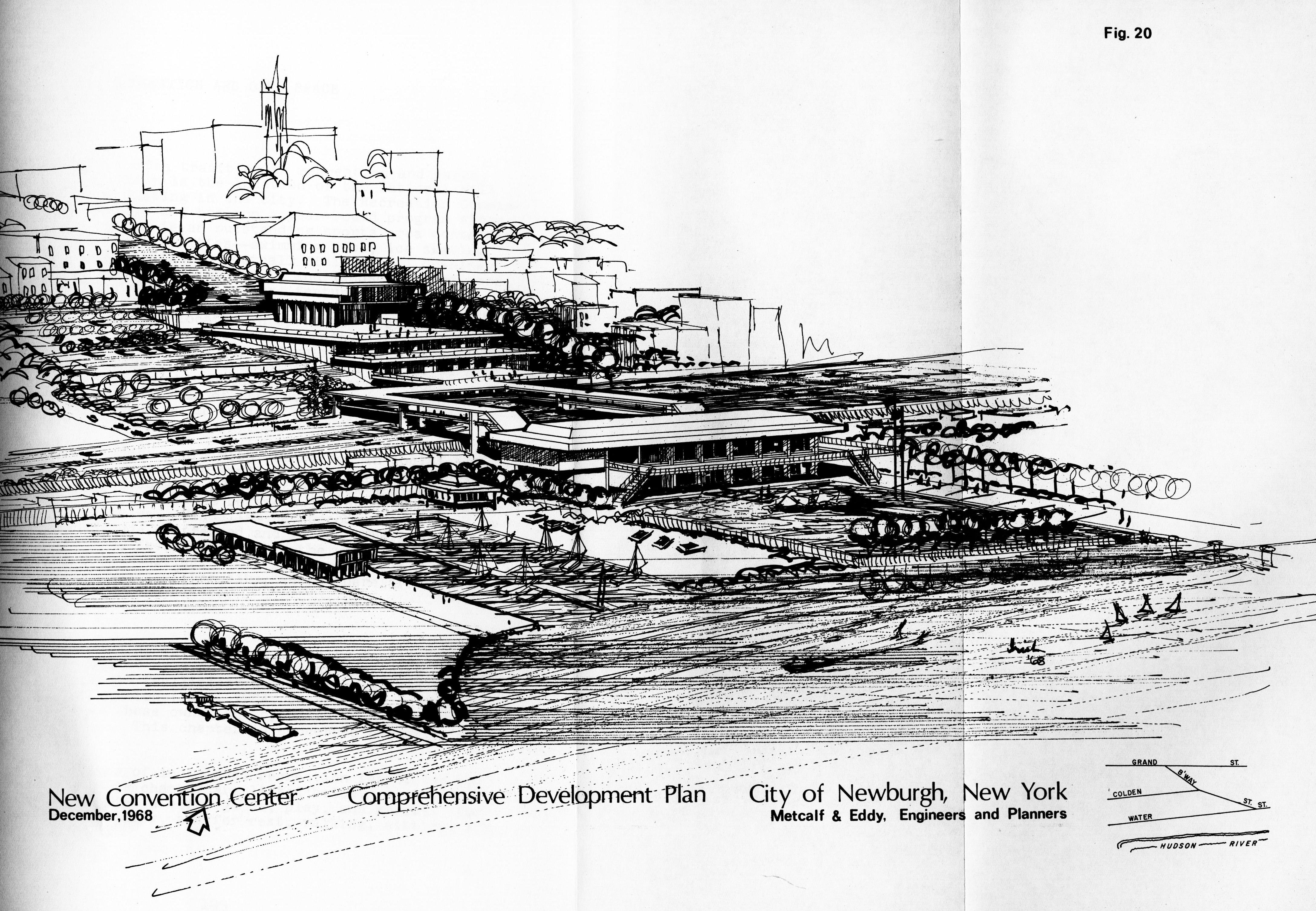

Re-thinking the Preservation of Places

In recent years, the National Trust for Historic Preservation has begun to look more closely at the impacts of preservation in cities through an initiative called ReUrbanism. Fundamental to ReUrbanism is the idea that building reuse encourages economic growth and stimulates vibrant communities. Through a variety of studies, the National Trust has found that mixed use neighborhoods are often more sustainable than those communities with a single building stock.[x] Many of the principles of ReUrbanism look toward creating equity in neighborhood development and planning, and derive from a broader conversation with the field about preservation planning in urban areas. In a piece for the Forum Journal’s issue on ReUrbanism, Justin Garrett Moore describes the need to change preservation and planning processes. The example he uses is a new community playbook in New York City. This Neighborhood Planning Playbook

includes tools designed to reveal the complexities of a neighborhood and provide a framework for comprehension, communication, education, and exchange with community residents and stakeholders. The playbook aims to help the city better study, develop, and implement plans for neighborhood change—and, most importantly, build public engagement and communication into all stages of the work.[xi]

Community engagement is a key piece of ReUrbanism. There is an evolving understanding that preservationists need to shift from an authority-based model to one that works in tandem with those who will be most impacted by preservation efforts.

Additionally, it is important to recognize that the protection of place also involves a full engagement in issues surrounding climate change. In her series on America’s Eroding Edges, Victoria Herrmann, a National Geographic Explorer and president and managing director of the Arctic Institute, examines the role flooding, coastal erosion, melting permafrost, and other climate impacts have not just on buildings and tangible heritage, but also on traditional cultural practices and entire communities. While it is paramount that we develop a robust set of strategies to adapt historic resources to climate impacts, these efforts must go hand in hand with conversations about economic and cultural equity and resilience.

In her 2018 TrustLive talk at PastForward, Herrmann discussed how in all of her conversations with communities impacted by climate change, the one consistent factor is that “climate change is the looming reality of losing the places and histories that make us who we are.” She continues to say that “climate change is not race, gender, or income neutral. Low-income communities, communities of color, and women are disproportionally affected by climate impacts. From centuries of discriminatory, social, and environmental policies, these communities have not been able to create the resources they need to prepare for and adapt to climate disasters.” With this in mind, inclusive preservation practice must include a recognition of climate impacts on communities; it is through dialogue and partnerships with organizations such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, 100 Resilient Cities, US ICOMOS, and the Association for Preservation Technology that the practice can move forward.

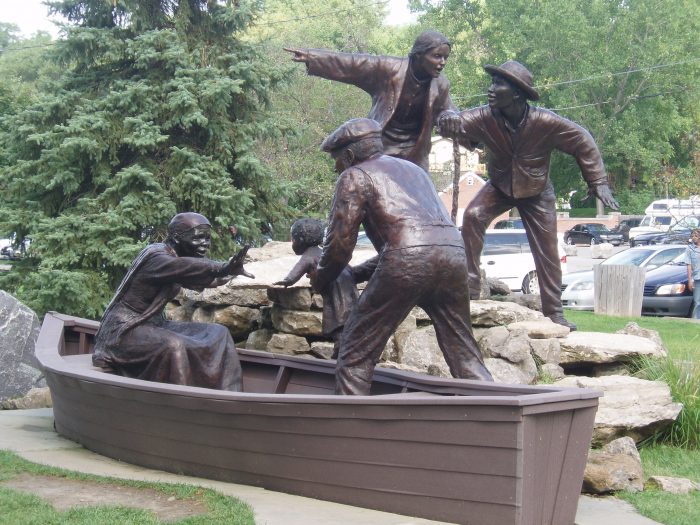

It is clear that many of the places currently being preserved only protect a fraction of historical narratives. Clement Price, who was a former Trustee of the National Trust and a Vice Chair of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, stated that broadening the spaces being preserved “connects very ordinary Americans with their personal histories, and in turn these histories connect with the larger narrative of making a more perfect and yet complicated union.”[xii] Examples of such places exist across the United States and, in recent years, some have become the focus of preservation efforts.

Two important examples are Tule Lake, a Japanese internment camp, and Rio Vista Farm in Texas, an agricultural site where migrant laborers from Mexico toiled. One site is evidence of the challenges to U.S. democracy that arose when segments of the U.S. population were unconstitutionally incarcerated due to racist fears and wartime hysteria; the other is a place that demonstrates how migrant workers from Mexico filled critical gaps in the U.S. agricultural labor system. In both cases, we find pieces of U.S. history that are often overlooked and, in doing so, begin to recognize the layers of experience and history that can be encountered in these places.

Speaking about sites such as Tule Lake, Cathlin Goulding writes, “Though the euphemisms for these places range, they all have in common a political climate of fear, suspicion, and hysteria and a system of governance wherein power is ultimately rooted in the ability to decide who can and does belong.”[xiii]

Inclusive Storytelling

The final pivot for preservation as an inclusive practice is something that runs parallel to work within both public history and museums: storytelling. In some ways this term feels like the latest buzzword across disciplines; nevertheless, it is an important piece of the broader mission of preservation as we strive to tell fuller and richer stories. In order to know what places to protect, we have to listen to the people to whom these stories belong; in doing so, it is important to recognize that these stories cannot be told using the same methods and practices as before. An inclusive preservation practice recognizes that preservation is not just about buildings and structures but also intangible heritage, which is often only available through conversations with community members.

Consider the work of the San Antonio Office of Historic Preservation, which uses a process called culture mapping to make connections to place and document change over time. Claudia Guerra, from San Antonio’s Office of Historic Preservation, describes the process where recorded narratives are paired with hand-drawn maps from community storytellers. She emphasizes the need to protect the intangible: “Safeguarding and preserving our heritage is what preservationists do, but preservation is about more than just protection—it is inherently about sharing.”[xiv] In her essay, she emphasizes a variety of tools and lessons critical to working with communities: “Listen more than you speak.” “Be prepared for unusual places to be documented.” And, “be aware and sensitive to the fact that similar cultural communities that share some traits may nevertheless differ widely in [their] thinking.”

In a sense, the importance of expanding preservation’s scope is to further build connections among people, places, and the past. In an interview for the Preservation Leadership Forum, Angelo Baca, filmmaker and cultural resources director for the Utah Diné Bikéyah, stated that “stories are very important because they hold knowledge. And it is important for us to understand that even the oral traditions, the legends, the myths, and all these things that talk about the time before what we understand now are actually . . . a resource.” For many Native communities, the importance of place is centered in both the tangible and the intangible. The identity of many of these communities is rooted not only in physical places but also the traditional knowledge embedded within those places.

Lisa Yun Lee, director of the National Public Housing Museum, says it best when she states “Our commitment to preservation and interpretation must always include a commitment not only to telling a narrative or presenting a counter-narrative but also to meaningfully empowering people to change the narrative.”[xv]

An Inclusive Preservation Practice

In the edited collection Bending the Future, Gail Dubrow, professor at the University of Minnesota, writes:

My vision and hope…is that these relatively new advocacy groups and constituencies move from the margins to the center of the preservation movement, bring their independent identity-based preservation interests into more effective alliances that bridge the divides of race, class, gender, and sexuality. While identity based politics have resulted in a more inclusive agenda for what we preserve, the democratic future of how we preserve depends on bringing their experiences, insights, and perspectives to bear on redefining the scope, policies, practices, and priorities of the preservation movement as a whole.[xvi]

Building inclusive preservation practices requires acknowledging the stories, places, and needs of all communities. Tried-and-true preservation tools need to be used in tandem with other methods and practices. Collaboration and partnership are essential to protecting places in a fair and equitable way.

Historic preservation can be a force for good rather than a tool of elitist forces, but in order to make it so, many of the field’s practices need to shift. This reorientation is essential because, as Tom Mayes, author of Why Old Places Matter, writes, “The old places of people’s lives are deeply important—more important than is generally recognized—because these neighborhoods, churches, temples, old houses, stone-walled fields, landmark trees, and courthouses contribute to people’s well-being, from that sense of identity and belonging, to the awe inspired by beauty, to the drive to build and sustain a greener and more equitable world.”[xvii]

Notes

[i] A growing conversation in the art community is centered around the vocabulary of placemaking. During a 2018 PastForward session Lauren Hood from Deep Dive Detroit talked about the concept of place-keeping where instead of coming into a neighborhood and rebuilding from the ground up, preservationists and art organizers work to support and sustain the cultural practices that already exist. In order to have an inclusive preservation practice, language is an important element to focus on. See also Erica Ciccarone, “Nashville Artist’s Aim for Place-keeping More Than Placemaking,” Burnaway, September 17, 2017.

[ii] Coined in 1989 by law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality is a term that examines the overlapping issues of discrimination within specific identities. That is, where stories of discrimination for black women are often connected to discrimination bias based on their gender and race. For the purposes of this essay, intersectionality uses that central definition as a means of storytelling, in which preservationists and historians tell the full history of the American past through the lens of overlapping identities.

[iii] Max Page and Marla Miller, “Introduction,” in Bending the Future: Fifty Ideas for the Next Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in the United States, eds. Max Page and Marla Miller (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 2.

[iv] Byrd Wood, ed. With Heritage So Rich (Washington D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1999), 194.

[v] David Brown, “A Preservation Movement for All Americans” in Bending the Future: Fifty Ideas for the Next Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in the United States, eds. Max Page and Marla Miller (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 59.

[vi] Brown, “A Preservation Movement for All Americans,” 60.

[vii] Stephanie Meeks, “Introduction: Our Future Is In Diversity,” Forum Journal: The Full Spectrum of History: Prioritizing Diversity and Inclusion in Preservation 30, no. 4 (Summer 2016): 9. There are a two significant programs that work to engage youth in preservation projects. The National Trust’s HOPE Crew focuses on training young people and veterans in historic trades. Another program, HistoriCorps, was inspired by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps to bring volunteers together to work on preservation projects. Both programs provide avenues of engagement outside of professional university training.

[viii] Sarah Zenaida Gould, “Latinos in Heritage Conservation,” in Bending the Future: Fifty Ideas for the Next Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in the United States, eds. Max Page and Marla Miller (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 89.

[ix] Meeks, 6.

[x] More detail on these ideas can be found in the National Trust for Historic Preservation research reports Older, Smaller, Better: Measuring how the character of buildings and blocks influences urban vitality and Untapped Potential: Strategies for Revitalization and Reuse.

[xi] Justin Garrett Moore, “Making A Difference: Reshaping the Past, Present, and Future Toward Greater Equity,” Forum Journal: Reurbanism: Past Meets Future in American Cities 31, no. 4 (2018): 23-24.

[xii] Clement Alexander Price, “The Path to Big Mama’s House: Historic Preservation, Memory and African-American History,” Forum Journal: Imagining a More Inclusive Preservation Movement 28, no. 3 (2014): 27.

[xiii] Cathlin Goulding, “Tule Lake: Learning from Places of Exception in a Climate of Fear,” Forum Journal: Preserving Difficult Histories 31, no. 3 (Spring 2017): 50.

[xiv] Claudia Guerra, “Culture Mapping: Engaging Community in Historic Preservation,” Forum Journal: The Full Spectrum of History: Prioritizing Diversity and Inclusion in Preservation 30, no. 4 (Summer 2016): 30.

[xv] Lisa Yun Lee, “The Stories We Collect: Promoting Housing as a Human Right at the National Public Housing Museum,” Forum Journal: Preserving Difficult Histories 31, no. 3 (Spring 2017): 17.

[xvi] Gail Dubrow, “From Minority to Majority,” in Bending the Future: Fifty Ideas for the Next Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in the United States, eds. Max Page and Marla Miller (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 74.

[xvii] Thompson M. Mayes, Why Old Places Matter: How Historic Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers/AASLH, 2018).

Suggested Readings

Baca, Alex. “Places Journal Reading Lists: Reading Cities.” Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/reading-list/reading-cities/.

Herrmann, Victoria. “Blog Series: America’s Eroding Edges.” October 1, 2018, https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/forum-online/2018/10/01/blog-series-americas-eroding-edges. More stories at www.erodingedges.com.

Mayes, Thompson M. Why Old Places Matter: How Historic Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers/AASLH, 2018). Blog Series here: https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/forum-online/2016/03/30/blog-series-why-do-old-places-matter.

Meeks, Stephanie K. “Presenting ‘Preservation for People: A Vision for the Future.’” Preservation Leadership Forum. May, 18, 2017, https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/stephanie-k-meeks/2017/05/18/presenting-preservation-for-people-a-vision-for-the-future.

National Council on Public History. “Special Issue: Conversations in Critical Cultural Heritage” The Public Historian 41, no. 1 (February 2019).

National Council on Public History. “National Historic Preservation Act Commemoration Series” History@Work blog, https://ncph.org/history-at-work/tag/national-historic-preservation-act-commemoration/.

National Park Service. “Theme Studies.” Accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalhistoriclandmarks/recent-theme-studies.htm.

- Finding A Path Forward: Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmark Theme Study. 2018.

- LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Transgender, and Queer History. 2016.

- American Latino Heritage. 2013.

Page, Max, and Marla Miller, eds. Bending the Future: Fifty Ideas for the Next Fifty Years of Historic Preservation in the United States. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016.

Preservation Leadership Forum. Forum Journal: The Full Spectrum of History: Prioritizing Diversity and Inclusion in Preservation 30, no. 4 (Summer 2016).

Preservation Leadership Forum. Forum Journal: Preserving Difficult Histories 31, no. 3 (Spring 2017).

Preservation Leadership Forum. Forum Journal: “Every Story Told”: Centering Women’s History 32, No. 2. Behind a Firewall Until 2020. Available on Project Muse.

Preservation Leadership Forum. Forum Journal: Imagining a More Inclusive Preservation Movement 28, no. 3 (2014).

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. “Culture Lab Playbook.” Accessed February 16, 2019, https://smithsonianapa.org/culturelab/.

UNESCO. “About Intangible Heritage.” Accessed February 16, 2019, https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003.

US/ICOMOS. “With a World of Heritage So Rich.” US/ICOMOS Organization Website. Accessed February 16, 2019 http://www.usicomos.org/about/wwhsr/.

Valadares, Desiree. “Places Journal Reading Lists: Race, Space, and the Law.” Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/reading-list/race-space-and-the-law/.

Various Authors. “Blog Series: When Does Preservation Become Social Justice.” Preservation Leadership Forum. July 26, 2017. https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/forum-online/2017/07/26/blog-series-when-does-preservation-become-social-justice.

Various Authors. “Blog Series: Women’s History and Historic Preservation.” Preservation Leadership Forum. September 13, 2017. https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/forum-online/2017/09/13/blog-series-womens-history-and-historic-preservation.

Author

~ Priya Chhaya is a public historian and the associate director of publications and programs at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. You can contact her through her website at www.priyachhaya.com.