Heritage tourism is focused on people, attractions, history, and activities that are particular to a region. The relationship between heritage travelers and museums and historic sites is a natural coupling of shared interests and intellectual curiosity. Heritage travelers are seekers of the authentic and unique and are, not surprisingly, frequent visitors to cultural attractions.

Attracting heritage travelers can be an elusive prize for museums and historic sites, and it often pays dividends to cooperate with cultural organizations. Some museums can experience spill-over visitation, or visitors drawn by other attractions or events in the area. A major attraction may open nearby, a new show or film may highlight a local story, and numerous other scenarios may bring new travelers and opportunities to your community. Ideally, tourism planning should be proactive and focused, so an institution is prepared to seize opportunities.

There are many things to consider as you assess the market readiness of your institution. Do you have a relevant, meaningful product? What is your reputation locally and beyond? Are you known beyond your local community? Is your staff fully ready to welcome an influx of visitors? An honest appraisal of institutional strengths and weaknesses is not just advisable but necessary.

Constant Ambassador

A “constant ambassador” is someone who recognizes that they are the public face of an institution during every visitor interaction and that it is part of their job to be kind, informative, and helpful. Regardless of role, everyone on staff must be enlisted as a constant ambassador for the site. Involve all staff, volunteers, and board members in customer service training. Whether a person is standing in a gallery or shoveling the front walk, they should know why the museum matters. All staff should also understand that visitors should feel welcome the moment they enter the grounds.

While museums are non-profit entities, some lessons can be borrowed from the corporate world. Consider the following points made by Kenneth B. Elliot, Vice President in Charge of Sales for The Studebaker Corporation in 1941.

The customer is not dependent upon us—we are dependent upon [them]. The customer is not an interruption of our work—[they are] the purpose of it. The customer is not a rank outsider to our business—[they are] a part of it. The customer is not a statistic—[they are] a flesh-and-blood human being completely equipped with biases, prejudices, emotions, pulse, blood chemistry and possibly a deficiency of certain vitamins.[i]

The ultimate fate of the Studebaker brand aside, the customer service message is clear: visitors should feel welcome. Some museum professionals regard the public as an invading army we need to defend against in order to protect resources in our care; when, in fact, everything we do is in the service of the public. Museums must always practice good stewardship, but that charge must be balanced with sufficient public access and engagement.

Balancing Stewardship and Visitor Experience

Preservation of the collection for future generations cannot exclude the needs of the present generation to develop an appreciation for and an emotional connection with objects or structures. We cannot assume that visitors will care about museum collections and programming if we cannot create points of relevance that resonate with them.

In historic house environments many people are still often forced to peer into rooms from a doorway behind a velvet rope. Is there a compromise that will allow visitors to have a richer experience? Has the option of putting down a runner on the floor and then roping off specific objects instead of full rooms been explored? A fantastic resource for this line of thinking is the Anarchist’s Guide to Historic House Museums, by Franklin D. Vagnone and Deborah E. Ryan; it is an in-depth exploration of the aforementioned ideas and much more.

One of the most detrimental ideas regarding tourism and museums is that it is purely a matter of advertising. There is a myth that if an institution can simply get its name/logo/website in front of tour operators and travel writers, its visitation will greatly increase. Building awareness is indeed important, but what are you building awareness of? Is the current visitor experience engaging and meaningful? Do the offerings reflect the communities around you? Direct engagement involves sharing ideas and fostering dialogue with visitors to help them shape their own meaningful experiences.

Scrolling down the lists of museum reviews on Trip Advisor or Yelp can be an eye-opening experience. In the realm of 1-star reviews you might find the occasional irate, perhaps unreasonable critic, but you might also encounter visitors who were deeply disappointed or so completely frustrated with their experience that they felt the need to publicly vent. If your institution is being blasted on social media, you need to respond briefly to let potential visitors know that you are taking their concerns seriously. Post your response for all to see and make every effort to talk personally to the visitor who made the complaint. Be sure not to get defensive or escalate an online argument; no institution is perfect, things happen, and people make mistakes. A complaint may run deeper than the experience of one visitor. The issue may reflect a larger problem, which when addressed might even turn a potential crisis into an opportunity for growth.

Telling Complete Stories is Good Business

The tourism market has become a diverse marketplace, and despite staffing and research limitations, there are opportunities and incentives to delve deeply into all of the stories that have influenced your site. It is easy to be completely drawn into the standard “hero narrative” and remain there. This is a limited perspective that often excludes indigenous people, people of African descent, the LGBTQ community, women across cultures, and people from diverse ethnic or class backgrounds. Take everyone into consideration, especially if a particular group has had a minor role in your story thus far; everyone has a point of view that should be taken into consideration. This is not a matter of political correctness. It is good history, and it will expand your audience.

Complete stories require the exploration of all available research resources, including the memories of former inhabitants of the site. Narratives based on the records of wealthy land-owning families are often a starting point, but we must go beyond the written record. The Lott House in Brooklyn, New York, for example, recognizes that enslaved Africans did not typically keep a written record of their experiences and employs archeological evidence to show that enslaved Africans maintained their own distinct spiritual lives.[ii] There are similar archeological finds in other portions of the state, including a coin found further north in Albany, New York, that was turned into an amulet resembling a dkinga, which shows the shape of the universe in West African cosmology.

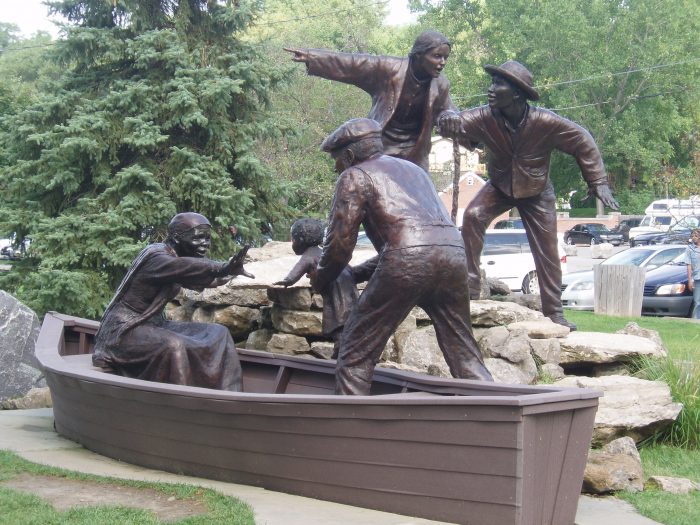

To attract and keep a more diverse audience, your story must have depth and reflect the experiences and culture of the visitors you hope to welcome into your institution. Enslaved people’s lives were never simply about the work they did. Their multi-faceted stories reflect their unique spiritual lives, foodways, music, and folklore, among many other things. By telling a multi-dimensional story, the ability to create points of connection may result in more meaningful experiences for visitors. It may be impossible for any visitor to truly understand the life of a person living in a state of slavery, but most people will understand an enslaved person’s desire for freedom, the need to pass on traditions to one’s children, or the longing to keep families intact, safe, and well.

What are the stories that have been ignored, undervalued, and deemed irrelevant? We are not just keepers of things, we are keepers of stories, history, and culture, and a portion of our histories are intangible. In a historic house environment, the intangible history may connect to the lives of enslaved people. The idea of delving into a complex story based on research and archeological findings from a similar site and time period with little-to-no direct material culture, strikes some as ill-advised and deeply problematic. But it is in many ways an opportunity to share history that is more balanced. We must untether ourselves from the notion that we can only tell stories if we have all of the belongings of the former inhabitants. Such projects may require outside partners, research, community outreach, and expertise in order to work. Finding alternative ways to share unexplored history is complicated, but can lead to a much richer visitor experience.

While many of the examples here focus on the African-American experience, the need to tell complete stories exists at nearly all institutions that interpret history. The important thing is to dig deep into the history of the site and surrounding community to shine a light on the groups that have been misunderstood, marginalized, or omitted from our shared history and to involve outside voices and perspectives in that process. Enlisting outside partners in this process is an important step. A community partner or advisory group must have a voice; a partner with no true input is not a partner. An advisor simply there to represent a group that has no substantive role is an empty gesture.

Diverse Audiences Matter

Imagine walking into a museum to visit a museum shop to pick up a gift for a friend. The place is nearly empty, the salesperson greets you as you enter the shop and begin to browse. As you scan a shelf, you notice that the security guard who was at the main entrance is now carefully searching the book volumes on a nearby shelf. As you make your way to the other side of the shop, you notice that he follows. Is this the kind of institution that you would continue to patronize or ever recommend? The aforementioned scenario is real and likely occurs more often than many museum professionals think or are comfortable acknowledging. Museums are public spaces for all people, and every person should feel valued. When we question whether or not a visitor belongs in a museum, we do a disservice to the public and we betray our core public service duties. We should not take for granted that everyone on staff understands that these are essential values of the organization.

African Americans spend $50 billion annually on travel and leisure experiences, and they support institutions that embrace diverse messaging and interpretation.[iii] Such institutions also serve as models for other organizations. Consider the case of Whitney Plantation in Louisiana. It is the state’s only plantation-based historic site focused entirely on the lives of enslaved Africans, and its honest interpretive approach has led to consistently high visitation and international media coverage. Whitney’s success has helped turn the standard plantation narrative on its head, and other plantation sites in the region have begun to tell more inclusive stories as a result.

Connecting with Tourism Professionals

Local or Regional Tourism Promotion Agencies or Agents (TPA) or Destination Marketing Organizations (DMO) are among the most direct lines to entering the tourism marketplace. It is the TPA’s main job to promote and sell the region as a travel destination. Make an appointment to see them and share your full event calendar, offer them a tour and an opportunity to evaluate your site, and inquire about a familiarization tour (“fam tour”). “Fam tours” are specifically for tour operators and travel bloggers/writers. They are designed to serve as extended, in-person advertisements for a region and often have a specific theme. Make a case why your museum should be included on these tours; tout your uniqueness, flexibility, and ways you can connect with various themes.

Think beyond the borders of what has traditionally been done and begin to consider what else can be done. Arts, culture, and history connect many different subjects. If the tourism marketplace includes food tours, then offer a history-related program exploring the foodways of your site. Consider a talk on what we can learn from dining and cooking scenes in art. Whether the topic is architecture, wine, or something else, dig deep within the knowledge of your staff and collection to tell a new story. Be forthright and make it clear to the TPA or DMO that you want them to visit and assess your institution. Accept the feedback, listen to their plans for further thematic tours and events, and suggest ways your institution can join in. Whether it is as a star attraction or a smaller supporting attraction, take the opportunity.

Choosing the right partner is not purely a matter of shared heritage; reputation, resources, and reciprocity are equally important. The same logic applied to choosing a board member or advisory group member can be applied to potential partners. Diversifying your organization at all levels is a critical concern. Does the prospective partner recognize that the organization needs to represent everyone in your community? Do this partner’s practices align with your core values? Does your partner have resources you lack regarding staff, facilities, or current offerings that will make programs attractive to diverse audiences? Establishing a relationship that works in tandem for both parties is critical to creating a sustainable partnership.

Investment and Return

There are few paths forward that do not involve shifting scant resources. Most institutions are not going to make a few changes and see their attendance double in two years. The benefit of taking your museum into the tourism marketplace is not solely a matter of increased visitation. Museums help raise the quality of life in communities and promote economic development—more businesses, more jobs, and rising property values. Restaurants, boutiques, and coffee shops all benefit from rising visitation. Local elected officials want to be associated with economic development and increased tourism. These relationships have the potential to yield benefits such as in-kind donations and increased media visibility. Most important may be the good will generated in your own community. The same new content that may draw an audience from abroad may give locals a reason to return or visit for the first time.

The important thing here is to keep moving forward. Remember the words of Star Trek Captain Jean Luc Picard, “It is possible to commit no mistakes and still lose.” Failure is part of the process; do not get discouraged. Evaluate, retool, and try again. There are all sorts of external factors and pressures that impact the tourism industry, many of which are beyond your control. Trying new things means accepting that there will likely be a mixture of both failures and successes. Failure is only final if you stop trying to move forward.

Notes

[i] “Interview with Kenneth Elliot,” Printer’s Ink, Vol. 197 (1941).

[ii] H. Arthur Bankoff, Christopher Ricciardi, and Alyssa Loorya, “Remembering Africa Under the Eaves,” Archeology 54, Number 3 (May/June 2001).

[iii] Fabiola Fleuranvil, “Black Travel Dollars Matter,” Huffington Post, May 23, 2017.

Suggested Readings

Hargrove, Cheryl. Cultural Heritage Tourism: Five Steps for Success and Sustainability. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield/AALSH, 2017.

Author

~ Cordell Reaves is Historic Interpretation and Preservation Analyst, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation.