The Lost Cause was a historical ideology and a social movement created by ex-Confederates that characterized the Confederate experience and defined its value for new generations. By the twentieth century, the Lost Cause became enshrined as part of the national story of slavery and the American Civil War era, and it evolved through that century’s most important revolutions. It was never just about the Civil War, but about slavery, Reconstruction, southern race relations, the place of the South in national life, and Americans’ self-identity. Today, the Lost Cause’s historical and cultural claims have been rejected by historians and museum professionals as a narrow distortion of history at best and a lie at worst, but many of its cultural tropes and political assumptions occasionally thrive, not only in the American South, but across the country.

Historical Claims

The Lost Cause began to emerge from “Ladies Memorial Associations” and men’s veterans groups in the late 1860s, and initially concerned itself with vindicating the Confederacy against ridicule and accusations of treason that ex-Confederates considered dishonorable. The term itself originated with Virginian Edward Pollard’s 1866 book, The Lost Cause. It matured in the late nineteenth century through historical writing, fiction, speeches, museums and shrines, reunions, monument building, funerals, magazines, and fundraising initiatives. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded in 1894) eventually became the chief propagators of the Lost Cause, but Confederate veterans, authors, academic historians, politicians, public historians, business leaders, and cultural producers all contributed to its life.

As a social and cultural movement, the Lost Cause was not monolithic. Some enlisted it to support Populist agrarianism in the 1890s, while others used it to promote the industrialization of the “New South.” Further, while it maintained a hostility to Unionist versions of Civil War history, it accommodated fraternal cooperation with United States veterans and support of patriotic adherence to the contemporary United States. In short, the Lost Cause could simultaneously revere an allegedly idyllic plantation life, condemn Abraham Lincoln, and rally southerners in contemporary American patriotism.

The Lost Cause maintained several basic historical claims that are now roundly disputed:

- That cultural and constitutional differences—not a singular interest in preserving slavery—forced the slaveholding states to secede. While denying the centrality of slavery to secession, Lost Cause authors consistently described slavery as a benevolent institution in which white and black southerners engaged in a reciprocal relationship that secured a domestic peace that abolitionists threatened.

- That Confederate armies—composed uniformly of gallant men and brilliant leaders—succumbed not because of poor leadership, sub-par military performance, or battlefield losses, but to overwhelming United States resources. In fact, a veritable religious cult developed around the Confederate pantheon of President Jefferson Davis and Generals Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee.

- It regarded Confederate women as sanctified by wartime sacrifice and identified, in them, perfect examples of gender conformity.

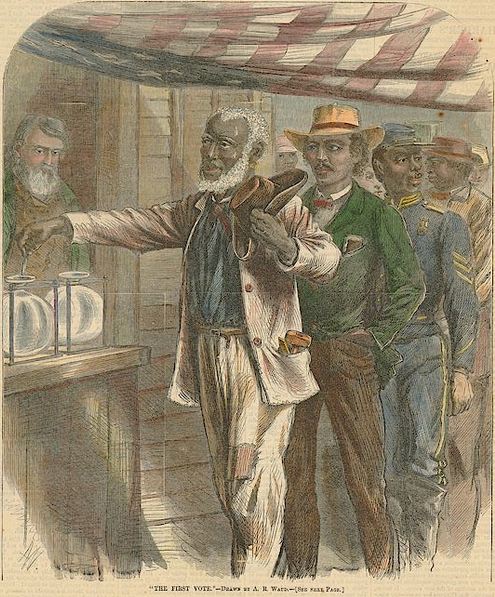

- Though ex-Confederates accepted the end of slavery, the Lost Cause maintained that because slavery had been beneficial to black and white people alike, emancipation had been a grave mistake. Further, it maintained that Reconstruction had been driven by a vindictive desire to impose a dangerous racial equality on a prostrate white South, and that the “redemption” of the South by Klan violence and electoral fraud had been a heroic moment in southern history.

By the early twentieth century, the Lost Cause had attained a status as the “official history” in the former Confederate states, as its promoters created a memorial and intellectual landscape that dominated public life. Veterans, the UDC, and countless municipalities erected monuments at a pace only outdone by the simultaneous erection of Union monuments in northern states. The UDC policed public school textbooks to ensure a history of the Confederacy that was “just,” censoring lessons that might be too admiring of Abraham Lincoln and too disparaging of Jefferson Davis, or which suggested that white southerners had been cruel slave masters determined to preserve slavery. Politicians and business leaders paid fealty to Confederate memory through designation of holidays and support for monuments, while civic boosters promoted tourism that venerated elite white historic sites, such as plantations and churches, and notable locations of wartime events like battlefields or the death sites of Stonewall Jackson, General J.E.B. Stuart, and Sam Davis. (Many of these sites still form the backbone of the modern tourism industry in several states.) Aside from the UDC, significant sources of the Lost Cause included the Southern Historical Society (1869), Confederate Memorial Hall (1891) in New Orleans, Confederate Veteran magazine (1893), and the Confederate Museum (1896) in Richmond, Virginia.

CULTURAL ASPIRATIONS

The Lost Cause was not just about the past. Among the white ruling class in the former Confederate States, it set expectations for the present and the future. It supported the white southern worldview that revered the past, deferred to elite rule, enforced conservative social values, exalted rural life, and marginalized black people.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Lost Cause offered guidance for people who were anxious about unchecked capitalism, mass immigration, and urban life. It defined slave plantations as pastoral idylls uncorrupted by the hurried pursuit of wealth. It looked to the courage of Confederate soldiers to steel the nerves of desk-bound corporate bureaucrats. In the wartime sacrifice of mothers and wives, the Lost Cause identified an admirable gender fulfillment against the growing suffrage movement.

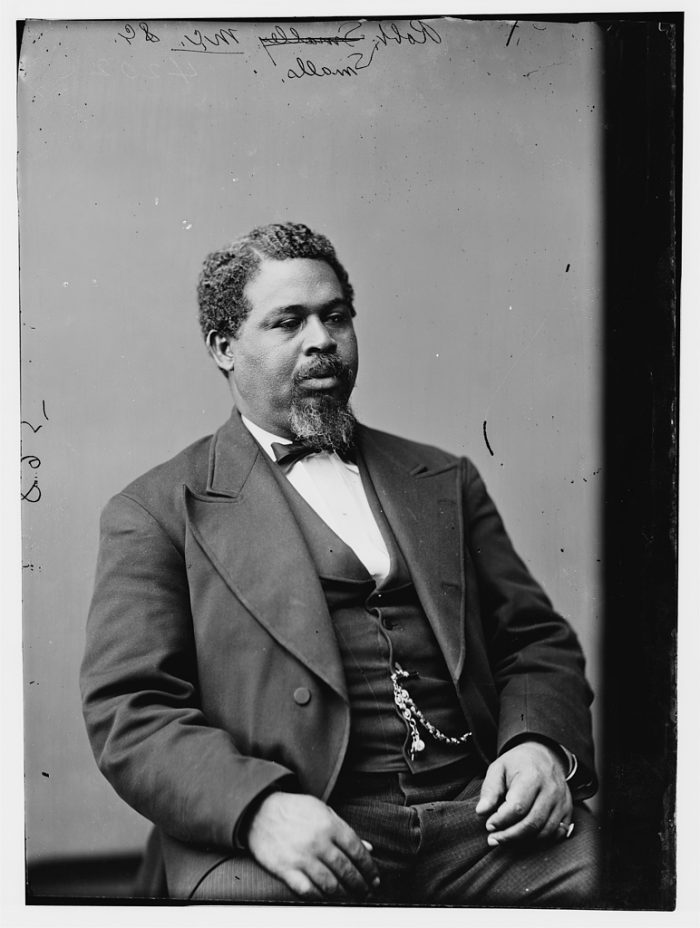

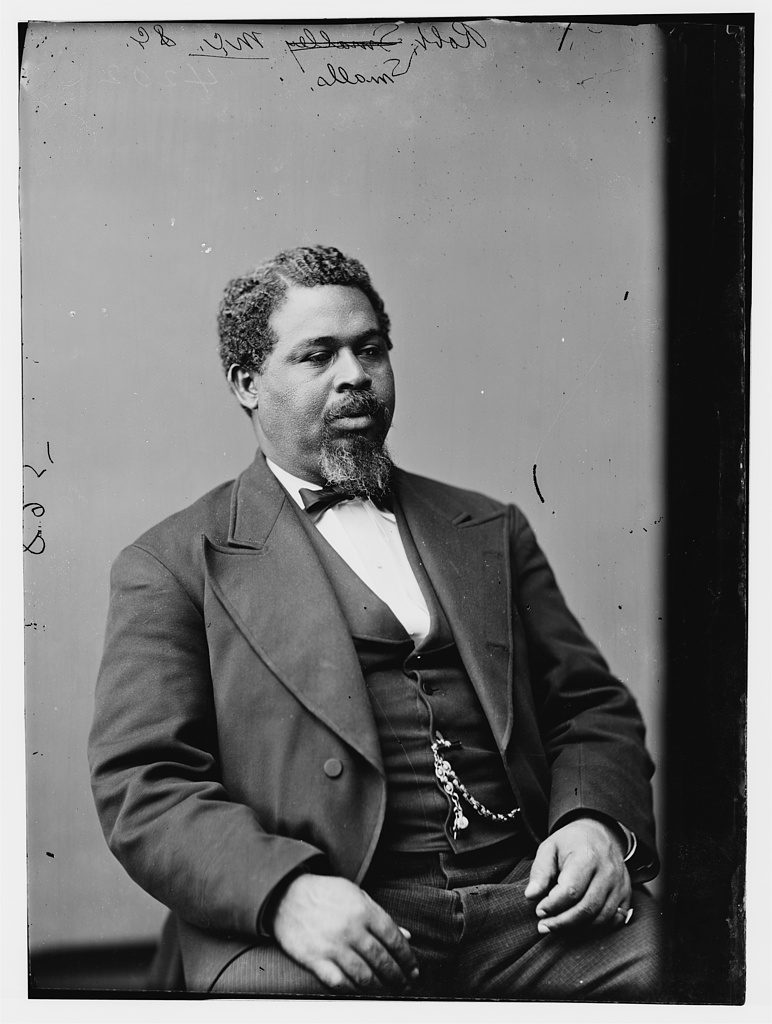

Most importantly, the Lost Cause perpetuated the narrative of racial difference that had begun in slavery, describing competent white people well-practiced in self-control and incompetent African Americans simultaneously unserious and dangerous, preferring loyal deference to actual participation in public and political life. The Lost Cause reliance on a history of white competency fit well with—and supported—the late-nineteenth-century white supremacist theorists who looked to a larger history of Anglo-Saxon self-governance combined with an evolutionary framework to determine that black people lacked the temperament and training necessary for democracy. In politics, these racist assumptions justified the entrenchment of Jim Crow segregation in turn-of-the-century southern state constitutions.

The Lost Cause celebrated and promoted black men and women who acted the parts of loyal and submissive servants. When white people leaned on that historical imagination of paternalism, some Lost Cause adherents—like Richmond, Virginia’s Mary-Cooke Munford and Rev. W. Russell Bowie—made anti-Klan and anti-lynching statements and joined in relatively liberal interracial cooperation initiatives. But, in its veneration of the Reconstruction-era Klan and rhetorical reliance on the fiction of black sexual rapacity, the Lost Cause made space for racial violence and lynching. For example, the favorite novelist of the Lost Cause—Thomas Nelson Page, who wove romantic tales of gallant young Confederates and loyal slaves—accepted lynching as a necessary evil to stem the alleged tide of black assaults on white women. In a self-fulfilling prophecy, when polemicist Thomas Dixon’s novel, The Clansman (1905), was turned into an early Hollywood blockbuster, The Birth of a Nation (1915), the movie sparked the creation of the “Second Klan” in the year of its release.

The Lost Cause became part of the national historical narrative of southern and Civil War history. It also attained academic sanction by historians such as Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, who called plantations a “school” for “civilization” for enslaved people, and William A. Dunning, who described Reconstruction as a period of carpetbagger corruption. These interpretations were never uncontested, particularly in popular settings. In the 1870s and 1880s, United States Army veterans and northern politicians regularly denounced the veneration of rebel leaders. Black journalists like Richmond’s John Mitchell, Jr., similarly condemned it, claiming in 1890 that white southern memorialization of the Confederacy “serves to retard [the South’s] progress in the country and forges heavier chains with which to be bound.” In the early twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois regularly critiqued the white southern fetish for Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee as indicative of larger social pathologies. Many more African Americans contended with the conservative social ethos that the Lost Cause undergirded. For instance, in 1904, Mary Church Terrell directly challenged Thomas Nelson Page’s theories of race, rape, and lynching. Later, scholars like Du Bois, Rayford Logan, and Carter G. Woodson wrote searching histories of black life before and after slavery that exposed the falsity of the Lost Cause view of race. Yet, the power of white supremacist cultural regimes ensured that these voices remained submerged.

ROMANCE AND TROPES

The Lost Cause gave rise to cultural tropes that shaped dominant public understandings of the Civil War and southern history—namely, the idea of plantations (and the American South at large) as sites of hospitality featuring white women “belles” as hostesses and black men and women as servants. These characterizations blended into mass culture as characters like Aunt Jemima sold pancake flour and beer companies compared their convivial brand promise to antebellum plantation barbecues. The 1939 film Gone With the Wind codified this imagery and made possibly the largest impact on public understanding of the Civil War in the twentieth century, creating a historical aesthetic replicated by hundreds of plantation tourist sites.

Similarly, the popular conception of the actual war came to be dominated by an almost exclusive focus on the Confederate and United States armies, their leaders, strategies, and tactics. The Lost Cause ideal of plantations and battlefield courage coexisted with a larger national paradigm about the Civil War that began during the Spanish American War and was nurtured in the Great Depression and World War II. It celebrated the national union that produced modern American power. The outcome was a focus on military tactics at public history sites that obscured the larger causes of the Civil War and muted any recognition that the Confederacy had fundamental differences from the United States in its outlook on race and cultural politics. The Lost Cause fixation on Lee and Jackson flourished in this environment. This military history, combined with conventional political histories that equivocated on slavery, dominated the Civil War Centennial celebrations between 1961 and 1965, and it thrived in mass produced toys like Marx playsets and in television series like The Gray Ghost (1957-1958) and The Rebel (1959-1961).

In the mass culture of the twentieth century that celebrated national stories, some threads of Lost Cause history—like the alleged Reconstruction-era oppression of white people by corrupt carpetbaggers—became universal in the dominant American story, regardless of region. These tropes settled firmly into the interpretation of post-World War II museums and historic sites. The Civil War became a story of a military contest among white men against a backdrop of southern belles and silly, but loyal, slaves. Even as segregation laws began to erode in the 1960s, this common interpretation at public history sites made for an exclusionary setting.

EVOLUTION AMONG REVOLUTIONS

After World War II, the Lost Cause continued to evolve in American life, even in the face of challenges to its dominance. In the academic world, historians such as Kenneth Stampp, John Hope Franklin, and John Blassingame undermined its basic historical assumptions. This generation wrote compellingly about the horrors of slavery and the resistance of black men and women to their oppressors. They portrayed enslaved people as human beings and agents in their own lives. At the same time, opponents of the emergent Civil Rights Movement harnessed Lost Cause racial tropes and Confederate iconography in an aggressively political fashion. Whereas the elite female protectors of Confederate history in the early twentieth century had done so through genteel ceremonies, ice-cream socials, fundraising, wreath-laying, and essay-writing contests, the new generation—growing ever-more blue collar and male—relied on that same history to fuel violent confrontations, the brandishing of Confederate flags at civil rights protestors, and the embrace of a militant Confederate cultural identity.

By the 1980s, mainstream museums and historic sites had begun to reflect the interests of social historians, and took African American history and interpretation seriously; while Civil War battlefields, both at National Park Service sites and state and local sites, continued to cater to the interests of military history aficionados. At the same time, Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990), though flawed in some ways, was a landmark in introducing the general public to contemporary interpretations of Civil War history that elevated social history and centered slavery and African Americans in the story.

The June 2015 murders of black worshippers in Charleston, South Carolina by a young white man who had expressed racial sentiments that would not have been unfamiliar to Thomas Nelson Page forced the most widespread reckoning with Confederate iconography in American public life to date. South Carolina removed the Army of Northern Virginia Battle Flag that had flown on its statehouse and grounds since 1961. New Orleans, Baltimore, and a few smaller cities and towns took down statues and monuments to Confederate leaders and soldiers. However, most monuments that were erected in the heyday of the Lost Cause remain in place.

TODAY

Outside of partisan heritage organizations like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and a few private and state funded historic sites, the Lost Cause in its fullest expression has no credibility. Some institutions born of the Lost Cause have adapted and evolved to reflect this ideology. For instance, Richmond’s Confederate Museum became the Museum of the Confederacy in 1976, with the intention of rooting its interpretation in modern scholarship and the new social history. It merged with another Richmond institution in 2014 to become the American Civil War Museum. In 2001, the National Park Service responded to audience needs, pressure from Congress, and the calls of academic historians to move its battlefield interpretation beyond just military tactics and topics to include consideration of the larger issues at stake in the war in its Rally on the High Ground initiative. Other institutions—most notably private plantation historic sites—continue to appeal to the alleged romance of southern agricultural life and avoid fully explaining slavery.

Yet outside of historic sites, museums, and academic history, popular conversations on social media and other informal arenas reveal that plenty of Americans continue to discount the cruelty of slavery, deny the role of the institution in secession, revere Robert E. Lee, and disregard the promise and tragedy of Reconstruction. A new, and false, historical claim that black men served in an integrated Confederate army is both an updated version of the loyal slave trope and a completely modern attempt to make the Confederate States acceptable to the world of diversity and inclusion. Lost Cause tropes rarely appear in credible historical publications or museums, but they continue to surface in popular expressions of white racial identity politics where resentment over African American history and a sense of beleaguered whiteness continues to permeate discussions.

TOWARD AN INCLUSIVE CIVIL WAR HISTORY AT MUSEUMS AND HISTORIC SITES

The Lost Cause did near-irrevocable damage to the long term inclusivity of museum and historic site audiences. In its original iteration, it directly supported white supremacy and racial exclusion. It fostered many racist assumptions and a very narrow narrative story of romantic plantations and courageous military actions. Therefore, museums and historic sites that approach southern and Civil War history need to be particularly careful not only to avoid perpetuating Lost Cause tropes, but also to develop interpretive and methodological approaches that actively refute its assumptions.

While a proven solution to the alienation of non-white audiences from Civil War era historic sites has yet to be discovered, some reconsiderations of interpretive and methodological approaches may be useful. For instance, do not use the word “yankee” when referring to United States soldiers, avoid calling northerners in the Reconstruction South “carpetbaggers,” and do not refer to the perpetrators of violence in Reconstruction as “Redeemers.”

Museum scholar Gretchen Jennings describes “institutional body language” as “messages that come through loud and clear even when the mission statement, website, and marketing materials say something different.” Intentionally inclusive voices in marketing and social media can be belied by interpretive programming that centers picturesque columned plantation houses, or that prevaricates about the Confederate cause and handles the experience of Confederate and Union soldiers as being without difference. This institutional body language includes the physical appearance of a museum or site. Many Civil War battlefields and sites continue to fly reproduction Confederate banners on flagpoles adjacent to national and state flags in front of visitor centers, and to sell Confederate themed memorabilia with no interpretive context in gift shops. This practice gives the impression that contemporary hateful practices are tolerated and possibly endorsed by the institution, or at least that the historical experience inside will be distorted in the name of “balance.” This practice should end.

Interpretive approaches should shift. For instance, the history of the Reconstruction era remains the most misunderstood aspect of the Civil War era (because it was written by Lost Cause authors). It should be relentlessly interpreted as part of any Civil War museum or site. The creation of the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park in Beaufort, South Carolina, will raise the postbellum period’s profile nationally and yield useful interpretive practices for other sites to adopt.

The Confederate experience should continue to be discussed. After all, the Confederacy was not an exceptional element in American history, but rather, it represents particularly American impulses regarding politics, culture, and race. Interpretation should intentionally avoid romanticizing the very real pain, trauma, and loss that southern people endured, but also fully cover moments of dissent, coercion, and disaffection in the South during the antebellum period, the Confederate years, and Reconstruction.

Similarly, interpretation at plantation historic sites should not romanticize the landscape, but clarify for visitors the core economic reason for plantations. It should also foreground (or at least equalize) the lives of enslaved people that lived on them. Stagville State Historic Site in North Carolina has done so for a generation, and others, like McLeod Plantation Historic Site in South Carolina, and the Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters in Savannah, Georgia have recently set new interpretive bars for centering the African American experience in Old South settings.

The usual academic grounding of good contemporary interpretation of slavery may often leave unacknowledged visitors’ need to process historical trauma in a safe and reflective way. Sites like Whitney Plantation in Louisiana and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama effectively incorporate artistic expressions of suffering and moments for memorialization that are usually lacking at museums and sites.

Finally, support front line staff with appropriate training. Many visitors may have a negative emotional reaction when encountering historical interpretation that conflicts with personally held beliefs. Useful is Julia Rose’s “loss-in-learning” methods wherein interpreters assist visitors through their process of grieving the loss of old knowledge and help them learn to accept new information.

Historians and museum professionals have rejected the Lost Cause for a generation, if not more, but much work remains. Any attempt to expand the meaning of southern history and the American Civil War era that continues to center slavery in the story and humanize the enslaved goes a long way toward eroding the Lost Cause.

Suggested Readings

Brown, Thomas J. Civil War Canon: Sites of Confederate Memory in South Carolina. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville, FL.: University Press of Florida; with a new preface edition, 2019.

Foster, Gaines. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Foster, Gaines. “Today’s battle over the Confederate flag has nothing to do with the Civil War.” Zocalo Public Square, October 23, 2018. https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2018/10/23/todays-battle-confederate-flag-nothing-civil-war/ideas/essay/

Hillyer, Reiko. “Relics of Reconciliation: The Confederate Museum and Civil War Memory in the New South.” The Public Historian 33, no. 4 (November 2011): 35-62.

Kytle, Ethan J., and Blain Roberts. Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy. New York: The New Press, reprint edition, 2019.

Levin, Kevin M. Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Palmer, Brian, and Seth Freed Wessler. “The Costs of the Confederacy.” Smithsonian Magazine (December 2018). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/costs-confederacy-special-report-180970731/

“Reconsideration of Memorials and Monuments” issue. AASLH History News, Vol. 71, No. 4 (Autumn 2016).

Rose, Julia. Interpreting Difficult History at Museums and Historic Sites. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Author

~ Christopher A. Graham is the Curator of Exhibitions at the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia.