The Reconstruction period following the American Civil War marked the transition from slavery to freedom and citizenship for nearly four million enslaved African Americans. Traditionally defined as running from 1865 to 1877, but perhaps more accurately understood as encompassing events taking place between 1861 and the 1890s, Reconstruction was a period of dramatic social, economic, and constitutional change for Americans north and south. While some of its transformations proved lasting, others were rolled back on a tide of violence within twenty years of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

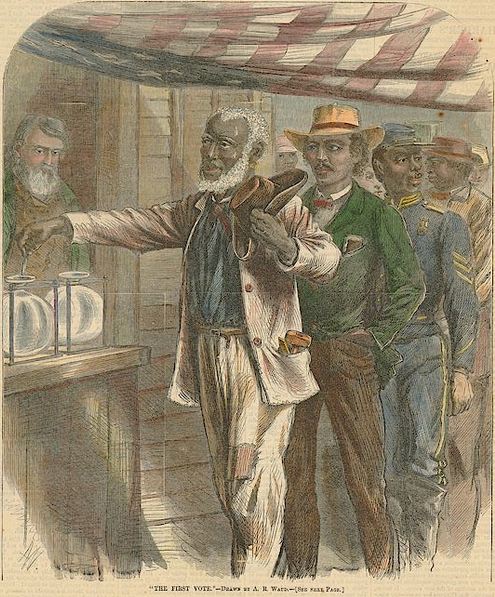

During the Reconstruction era, voters ratified three new constitutional amendments, including one that redefined citizenship in the United States, and Congress passed the first federal civil rights laws in American history. Black men and women sought to define freedom through reordering their daily lives; asserting their rights as free laborers; pursuing access to land; establishing community institutions such as schools and independent black churches; and reestablishing family bonds that had been torn apart under slavery. Black men began to organize politically, and after 1870, to exercise the right to vote, even in the face of intense and frequently violent opposition from southern whites.

Free public school systems emerged across the South during Reconstruction, and constitutional conventions rewrote southern state constitutions. Economic modernization and debt relief became key economic issues across the formerly Confederate South, and the first black colleges in the region opened their doors. In the American West, Reconstruction propelled the expansion of the reservation system and the end of federal willingness to treat tribes as sovereign nations, as well as gave rise to heated conflicts between a federal government that sought to “subdue” native populations and Native Americans who had no desire to enfold themselves into the expanding American republic. Economic panic struck the nation in 1873, the women’s rights movement fractured over the issue of black male suffrage, and a series of fraudulent and violent elections unfolded across the South. In the 1870s and 1880s, the Supreme Court issued a series of decisions that rendered the Reconstruction amendments nearly unenforceable; and mass-scale violence and political terrorism paved the way for the restoration of white supremacy in the South.

Changing Interpretations

Reconstruction is one of the most important—yet least well-understood—periods in American history. For generations, scholars influenced by the Lost Cause portrayed Reconstruction as the lowest point in American history, a period characterized by political corruption and retaliatory action against former Confederates, which “mercifully” came to a close with the withdrawal of the U.S. Army and the restoration of “legitimate” (i.e., white) government in southern states in 1877. Generations of Americans grew up with this deeply racialized interpretation of the era, which implicitly (and at times, explicitly) justified white supremacy; expunged the complex history of community-building, labor negotiation, and political action by freedpeople; and vilified black southerners and their white allies as corrupt, incompetent, and dangerous.

As historian Eric Foner argues, “historical writing on Reconstruction has always spoken directly to current concerns,” and in the wake of the mid-twentieth-century freedom struggle that toppled the system of racial control established in the wake of the Civil War, scholarship on Reconstruction has dramatically transformed.[i] Most scholars now understand the period as one characterized by an expansion of democracy and civil rights, a noble, albeit unsuccessful, attempt to transform the United States into an interracial democracy. In current scholarship, Reconstruction’s most tragic feature is understood to be the fact that it ultimately failed to solidify and sustain the economic, political, and social transformations that it promised. But scholars actively stress its successes in the face of tremendous opposition: particularly the schools, churches, mutual aid societies, clubs, and other community institutions built by freedpeople, and the concessions they forced white landowners to make in the struggle to determine the role of the black laborer in the postwar South.

Public Understanding of Reconstruction

Yet scholars’ understanding of the era as characterized by an expansion of democracy only reaches so far. As Foner has contended, “For no other period in American history does so wide a gap exist between current scholarship and popular historical understanding.”[ii] The era often gets short shrift in many K-12 history curriculums, and sometimes in college classrooms as well, due to its complexity and its timing, and—with notable exceptions—Reconstruction continues to be broadly underrepresented and under-interpreted on the nation’s public history landscape. The consequences of this marginalization are real, and troubling. When the Civil War era is artificially divorced from its aftermath, the long legacies and unresolved questions of the war years can be easily subsumed in a wave of romantic nostalgia. Disassociating the Reconstruction period from the war makes it possible to cast the fierce debates over Confederate memory that have convulsed communities in recent years as a simple matter of “preserving history” versus “erasing history,” rather than as struggles to understand how constructed narratives of Confederate and postwar history have been used to legitimize the restoration of white rule.

Americans’ poor collective understanding of the triumphs and failures of the Reconstruction era also affects our ability—as a society—to have thoughtful, honest, and historically-informed conversations about many issues that are hotly contested in today’s world. The definition and boundaries of citizenship; the relationship between political and economic freedom; the appropriate federal response to episodes of terrorism; concerns about election fraud and voter suppression; and the relationship between the federal government and individual Americans may be contemporary questions, but the way we experience them in the present has been shaped in part by the legacies—plural, not singular—of Reconstruction.

Contemporary Examples of Public Interpretation of Reconstruction

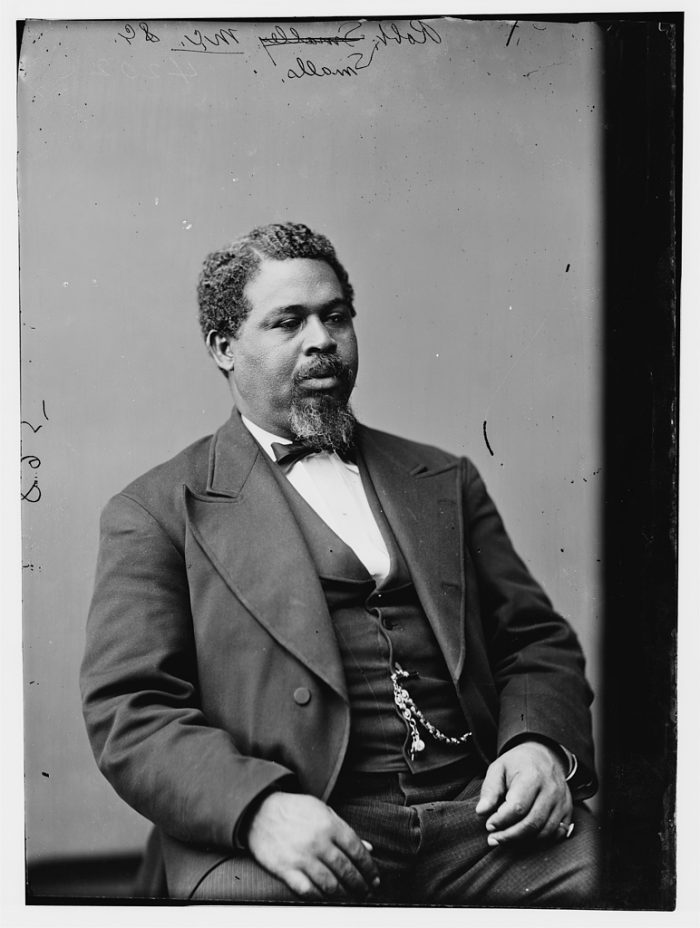

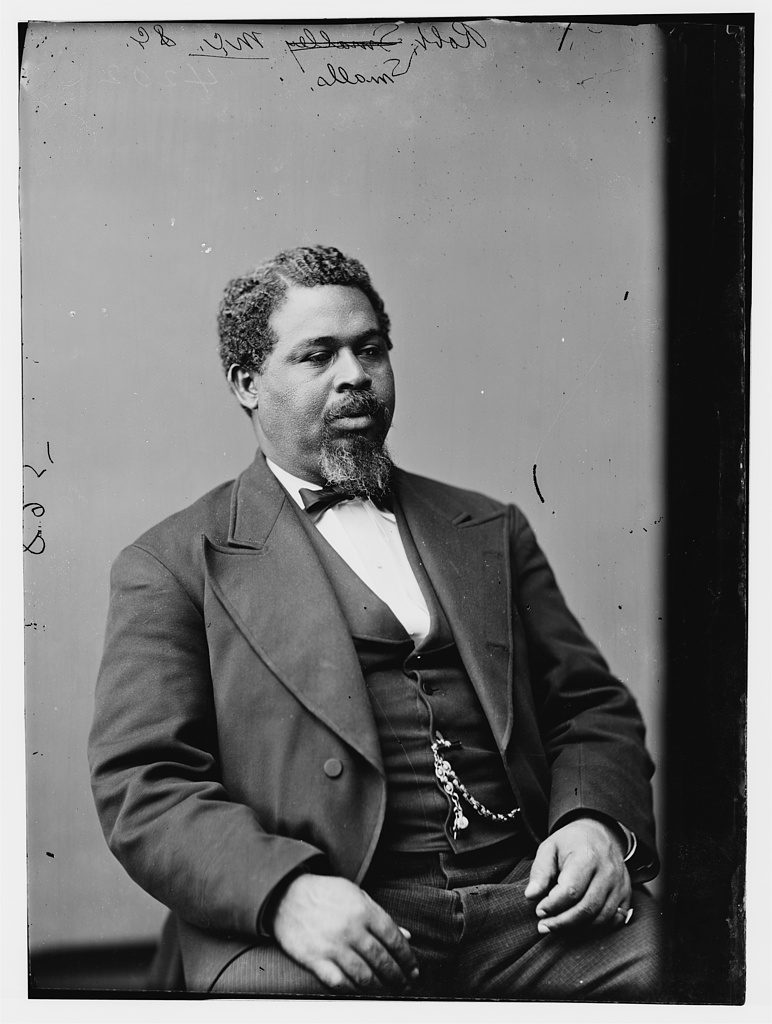

Though Reconstruction is still under-interpreted on the public history landscape, great strides have been made in recent years. Although some of the National Park Service’s Civil War battlefield parks, presidential sites, and homes of eminent black leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Maggie Walker have been introducing visitors to certain aspects of the period for years, the NPS did not have a site primarily devoted to Reconstruction until 2017. Reconstruction Era National Monument, an assortment of sites located in and around Beaufort, South Carolina, is the culmination of a fifteen-year effort to highlight and protect buildings and landscapes associated with the transition from slavery to freedom. Beaufort, which came into Union hands early during the war, was the site of a wartime community where freed people farmed confiscated lands, attended schools, governed themselves, and supported the Union war effort in numerous ways. Their efforts convinced many observers that free labor would transform the South and built support for black education, voting rights, and land reform among progressive white northerners. Beaufort was also the home of Robert Smalls, a formerly enslaved sailor who commandeered a Confederate vessel and sailed it to Union lines in 1862, freeing himself, his family, and 14 others. In the aftermath of the war, Smalls purchased his former owner’s house, and represented his home area in the state legislature, state senate, and U.S. House of Representatives, where he championed free public education and public support of the elderly.[iii]

The monument was designated by President Barack Obama, using the president’s executive powers under the Antiquities Act, leaving the door open to congressional designation of other sites of significance. The NPS’s 2017 National Historic Landmarks theme study on Reconstruction, spearheaded by historians Greg Downs and Kate Masur, has identified a wide range of additional sites that hold great significance for public understanding of the Reconstruction era. Some of these properties already bear landmark status, and some would require further study prior to potential designation. Put simply, Reconstruction’s complexity, significance, and long legacy will be best served by preservation and interpretation across a broad network of sites—both inside and outside of the NPS—rather than restriction to a handful of specifically designated properties.

One site where important preservation and interpretation work is already going on is New Philadelphia, Illinois, the first town in the United States to be founded, planned, and registered by an African American, Free Frank McWhorter. Though founded in the 1830s, the population and prosperity of the town peaked during Reconstruction, when it functioned as a multiracial community in which African Americans owned land and property, sent their children to school, and exercised political rights. Beginning in the late 1990s, descendants, local residents, archaeologists, and historians have come together to mark, excavate, preserve, and interpret the site. Like many sites associated with Reconstruction, no extant buildings survive, and those committed to providing visitors to New Philadelphia an educational experience have thus pursued Augmented Reality (AR) technology as a means to interpret the site. New Philadelphia’s AR walking tour embeds the stories of the people who lived, loved, and struggled there into the physical space, anchoring this past on the contemporary landscape. In so doing, AR allows “historically significant landmarks that have traditionally fallen outside of the notion of authorised heritage discourse—but which are no less important—to be brought into the fold of public consciousness through a new means of experiencing the past.”[iv]

In cases where surviving buildings do exist, they are being used to give voice to a wide range of historical experiences and perspectives. The centerpiece of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Reconstruction exhibit is a home built in the 1870s by Richard Jones, founder of a Maryland freedmen’s settlement. The museum presents the home as “a tangible symbol of Reconstruction,” a testimony to African American creativity and engineering skills, and a window into both the physical hardships of freedmen’s lives and their aspirations for the future. Conversely, in Columbia, South Carolina, the boyhood home of Woodrow Wilson has been transformed into a museum dedicated to exploring how Reconstruction played out in the city, and across the state more broadly, which in 1868 became the first to elect a black-majority legislature. The museum confronts topics head-on that receive little coverage elsewhere, such as the transition from enslaved to paid domestic servants, the temporary desegregation of the University of South Carolina, the formation of black churches in the city, and the rise of political and racial terrorism across the state. Though the connections between the larger narrative and the Wilson family’s own politics are not always clear, the irony of the home of a man who played a significant role in the campaign to discredit Reconstruction being reinvented as a place for visitors to grapple with the era and its legacies is remarkable.[v]

On the digital front, the After Slavery Project houses an array of primary source materials, interpretive essays, and interactive timelines and maps on Reconstruction in the Carolinas, most of them centering on labor. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture has launched a crowdsourcing effort to transcribe nearly two million files from the Freedmen’s Bureau records, an initiative that not only makes essential Reconstruction-related materials newly available online, but invites digital volunteers to read, transcribe, and otherwise actively engage with the records. These are only two of an assortment of digital resources now available to assist those interested in better understanding, contextualizing, and reanimating the narratives of this still widely-misunderstood era.

Conclusion

Given the deep-seated misconceptions that have long characterized Reconstruction in the public mind and the continuing underrepresentation of the period in much of the public history realm, it is crucial that public historians make a concerted effort to address the post-Civil War years through as many avenues as possible. Improving public understanding of the Reconstruction period can not only provide vital historical context for many contemporary debates, it can also shed important light on the workings (and failings) of democracy in a highly fractured society. Finally, educating the public about Reconstruction can provide an excellent case study for discussing how and why interpretations of the past change over time.

Notes

[i] Eric Foner, “Epilogue,” in The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook, eds. Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar (Eastern National, 2016), 179.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] National Park Service, “The Era of Reconstruction, 1861-1900: A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study” (National Park Service, 2017), 103, 111; Cate Lineberry, “The Thrilling Tale of How Robert Smalls Seized a Confederate Ship and Sailed it to Freedom,” June 13, 2017, Smithsonian.com, accessed May 19, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/thrilling-tale-how-robert-smalls-heroically-sailed-stolen-confederate-ship-freedom-180963689/.

[iv] Paul Shackel, New Philadelphia: An Archaeology of Race in the Heartland (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 38; Jonathan Amakawa and Jonathan Westin, “New Philadelphia: Using Augmented Reality to Interpret Slavery and Reconstruction Era Historical Sites,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24, no. 3 (November 2017): 317, 321, 327, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13527258.2017.1378909.

[v] Kriston Capps, “Rebuilding a Former Slave’s House in the Smithsonian,” The Atlantic, September 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/09/this-old-house/492767/; Lauren Safranek, Review of Woodrow Wilson Family Home, The Public Historian 37, No. 2 (May 2015): 121-123.

Suggested Readings

Capps, Kriston. “Rebuilding a Former Slave’s House in the Smithsonian.” The Atlantic, September 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/09/this-old-house/492767/.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Egerton, Douglas R. The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Foner, Eric. A Short History of Reconstruction. Updated Edition. New York: Harper, 2015.

National Park Service. “The Era of Reconstruction, 1861-1900: A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study.” National Park Service (2017). https://www.nps.gov/nhl/learn/themes/Reconstruction.pdf.

“Reconstruction in Public History and Memory at the Sesquicentennial: A Roundtable Discussion.” Journal of the Civil War Era 7, No. 1 (March 2017): 96-122. https://journalofthecivilwarera.org/forum-the-future-of-reconstruction-studies/reconstruction-in-public-history-and-memory-sesquicentennial-roundtable/

Safranek, Lauren. Review of Woodrow Wilson Family Home. The Public Historian 37, No. 2 (May 2015): 121-123.

Sutton, Robert K., and John A. Latschar, eds. The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook. Eastern National, 2016.

Author

~ Jill Ogline Titus is Associate Director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College and a former seasonal historian for the National Park Service. She is the author of Brown’s Battleground: Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia (University of North Carolina Press, 2011) and is currently at work on a study of the convergence of civil rights, Cold War politics, and historical memory during the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. She can be reached at [email protected].