The history of sexuality is a history of bodies—how they fit together and find pleasure—and of minds—how desire and pleasure are experienced and rationalized given social and cultural norms and political ideologies. Public-facing histories (like twentieth-century LGBTQIA+[i] activisms) lend themselves well to the excavation of primary source materials—newsletters, picket signs, photographs, etc.—and their respectable interpretation (de-sexualized narratives of identity and equal rights). However, the inclusive historian must remain cognizant of who produced and preserved what evidence, when, where, and why—and how it has been and will be understood by new generations and audiences. This information shapes and comprises extant narratives of sexuality.

Much of human sexuality has played out behind the bedroom door of history, private and concealed. The evidentiary basis for such history is scant. As an inclusive historian, it is your job to expand how these histories can be told using the resources available to you. How can we commit to being more inclusive, equitable, and service-oriented historians given the gaps and silences of the archive? We must always consider who or what is missing from our narratives, and why. Even given a wealth of materials and perspectives, how can we showcase the breadth and depth of sexual experience throughout human history given respectability politics, institutional censorship, and cultural expectations? Studying the history of sexuality brings with it questions of (in)decency and taboo, sex and gender norms, anachronism and bias—all of which create a maze of roadblocks the inclusive historian must continually navigate. This article will equip you with the tools necessary for understanding these challenges, the complexity of the history of sexuality, and examples of best practices for interpreting it.

Defining Sexuality

For the purpose of this article, sexuality can be taken to encompass the following:

- Sexual orientation—an internal experience, our desires or lack thereof, and who we are or are not attracted to.

- Sexual behavior—an external and usually private experience, the acts we do or do not engage in, and with whom we do or do not share them.

- Sexual identity—an external and usually public experience, how we conceive of our sexual experience and what we call ourselves.

These concepts are crucial for an inclusive historian to understand when interpreting sexual experiences of the past. As will be discussed in a later section, the frameworks and language we employ to encapsulate sexuality often present social, cultural, and political biases.

Historicizing Sexuality

Historical actors’ desires, actions, and identities will not always coincide with our expectations. In fact, they rarely do. Take, for example, Michael Wigglesworth, a seventeenth century Puritan minister known for his best-selling poem The Day of Doom. An ardent Christian, father, and husband three times over, Wigglesworth struggled with his sexuality, as revealed through diary entries. An inclusive historian would not automatically declare him “gay” or “prudish” upon learning of his attraction to his male students and his shame about nocturnal emissions. Instead, the inclusive historian would differentiate his inner thoughts and desires (evinced in his diary) from his actions (marriage and children) and identity (or lack thereof).

An inclusive historian is wary of presentist assumptions about the sexuality of historical actors. Modern identifiers like “gay” or “homosexual” reinforce anachronistic ideas about how sexuality was experienced in the past. These words come with their own social, cultural, and political connotations. In the history of sexuality, language serves a very important purpose— contextualizing a specific time and place, and how a particular desire, act, or identity was named (if it was named at all). Wigglesworth serves as a nexus between Puritan sexual mores, their internalization, and individuated experiences of desire. In order to responsibly interpret his history, one must ask how he experienced his sexuality as well as how it might have been read by others. Did Wigglesworth identify himself as part of a nameless underclass of “sodomites” persecuted by society or as a sinner comparable to a drunkard or a murderer? Is the “incongruity” between Wigglesworth’s desires and behavior something to be read as a lack of self-acceptance (by today’s standards) or a spiritual struggle (by Wigglesworth’s own perspective)? The inclusive historian must balance the agency of historical actors (like Wigglesworth) to conceive of their experiences on their own terms, with a critique of the social, cultural, and political constrictions placed on them that shaped their self-conceptions.

American scholar David Halperin once argued that sexuality “is a cultural production: it represents the appropriation of the human body and of its physiological capacities by an ideological discourse.”[ii] In other words, sexuality is a social construct and it is our job, as historians, to trace its genealogy—how experiences and conceptions of sex[iii] have changed over time. As French philosopher Michel Foucault argued in The History of Sexuality, sexuality has been framed by power dynamics that constitute “normal” and “abnormal” sexual experience.[iv] When we say that present-day American society is cisheterocentric,[v] we mean that it continually reinforces those norms about how sexed bodies and sexuality are experienced and described. But was this always the case?

The Importance of Language and Cultural Context

Queer theory serves as a useful framework for the inclusive historian because it encourages us to examine the sexual norms of a given context. “Queerness” (or what a given society deems sexually deviant) is a fluid concept and subject to change. Essentialists argue that sexual experience is innate to historical actors—that people are born with immutable desires. This position often connects to “born this way” and “gay gene” rhetoric, seeking scientific evidence to validate the experiences of queer people. While an important agenda, especially in campaigns against gay conversion therapy, essentialism is also tied to a long tradition of sexological activism and the medicalization of queer experiences. It also tends to conflate orientation and identity—such that “gayness” itself is timeless and universal, rather than homoerotic desire. Conversely, social constructionists find that sexual experiences are shaped by social, cultural, and political contexts—especially behavior and identity. Even if certain sexual desires are inborn, they, too, can be shaped by a person’s environment.

“Gender and sexuality inclusion” is typically considered a catch-all for (or, alternative to) the lengthy acronym of LGBTQIA+. But it has the potential to be much more than that. As inclusive historians, we recognize LGBTQIA+ identity is a specific set of identities, subsumed within a political movement that emerged from a particular time and place. Such terminology, its predominately Euro-American, present-day connotations, threatens to limit the scope of our scholarship. In reading backwards western queer experiences, historians have haphazardly applied modern identities to the sexual past and sought to derive a progressive political narrative. The inclusive historian must contend with this combination of presentism and Euro-Americanism. The misapplication of terminology such as gay, homosexual, or queer to sexual desires and behaviors of the past allows historians to describe non-normative experiences in terms relatable to present-day Euro-American audiences.

However, in order to best interpret and delineate queer histories, we must emphasize relevant temporal and geographic contexts—so as to avoid imposition of modern meanings and allow narratives of non-normative eroticism to emerge on their own, with their own language and self-conception. For example, Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley, Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, argues—“the many vocabularies possible under the umbrella ‘women who love women’ work to dismantle the closet by decentering it, by positioning this trope in a spectrum of constructions of sexuality in which mati, zanmi, bull dagger, or lesbian all carry their own cultural and historical weight.”[vi] Likewise, consider nineteenth-century German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, who originated the identifier Urning (also known in English as Uranian) as a way of describing his inner desires. An attraction to men, Ulrichs believed, was an inherently feminine attribute. Consequently, he considered himself and others like him to be part of a third sex—with female sex drives (or psyches) and male bodies. In a conflation of what would now be considered intersexuality, transgender identity, and homosexuality, Ulrichs’ self-conception demonstrates the historical construction of sexed bodies and desires. Sex, gender, and sexuality have not always existed as separate concepts and, indeed, still do not in some cultures. The inclusive historian takes these facts into account when studying unfamiliar contexts.

Similarly, the expansion of queer American histories into nonwestern contexts necessitates a broadened vocabulary to describe sexual experiences. The globalization of queer narratives presents the conundrum of a neocolonial occupation of nonwestern epistemologies. For example, localized identities may be reclaimed from precolonial times and/or originated in the present-day to dispute the claimed universality of Anglo sexuality. Their persistence is irreducible to the American constructs of gay, homosexual, or queer. Localized identities directly oppose Euro-Americentrism in queer history because, as in all transnational and cross-lingual surveys of sexuality, translation is an act of approximation and cultural connotation is never fully captured. Therefore, sexual histories in nonwestern contexts are entities unto themselves and should not be treated otherwise. For example, tongzhi is the contemporary Chinese word for a member of what westerners might call the LGBTQIA+ community, but was specifically adopted to counter Anglo identifiers. In other words, even if tongzhi is a modern identity, it may be anachronistically (mis)applied to Chinese history more readily than queer, which is not only anachronistic, but Euro-American in origin. The inclusive historian aids in the decolonization of history through selective language choice.

Modern distinctions of eroticism and romance between women is another example of how language informs the history of sexuality. Queer historians tend to resist ascribing “queerness” to female relationships, and are hyper-vigilant about presentist interpretations of affection. In lieu of same-sex sexual encounters, queer women are often said to have “romantic friendships” due to the absence of an explicitly articulated physical component to their bonds. Most queer women’s narratives rely upon private experiences articulated in the form of correspondence and journal entries, rather than more public records of the court and early activist treatises because female same-sex activity was rarely criminalized. Thus, historical work that glosses over the lives of queer women rests both in the seeming limitations of available primary source materials and in the phallocentric interpretations of extant evidence—in other words, claiming what constitutes intimacy (i.e., penetrative).

We must also bear in mind that queerness, while particularly relevant to a discussion of inclusive language, is only one facet of many in the study of the history of sexuality. Indeed, normative sexual desires, acts, and identities (and the language used to describe them) are much easier to excavate because they were openly reinforced rather than marginalized or erased from history. For example, Tom Reichert, Professor of Information and Communications at the University of South Carolina, considers how capitalism has reproduced cultural ideas about bodies, pleasure, and self-conception in The Erotic History of Advertising. Or we may consider the liminality of normative taboos and subcultures—wherein “acceptable” heterosexual desires and behaviors manifest in “unacceptable” contexts such as pornography or sex work. In turn, such experiences are re-eclipsed in the archive.

Ultimately, inclusive historians reorient themselves in an attempt to understand a different sexual experience or perspective, rather than fit those narratives into modern frameworks that are palatable to general audiences. The inclusive historian is successful in educating their audience about unfamiliar or even uncomfortable sexual experiences that challenge their preconceived notions on how sexuality may be experienced, acted upon, or identified.

Collection & Preservation: Considering Your Audience, Crafting the Narrative

The inclusive historian prioritizes provenance. The history of sexuality is often erased from lack of preservation of materials or, when materials are available, from a lack of context. As a collector for an archive, museum, or other repository, one must bear in mind how important source information is for interpretation.

For instance, many of the pornographic films at the Kinsey Institute Library and Archives—one of the largest repositories of sexual history in the United States—were acquired from anonymous donors. Beyond the occasional date of production, no information is offered regarding where the films were produced, by or for whom, or even how they were acquired and viewed. Understandably, taboo and stigma may have prevented the donors from revealing this information or even their identities. However, we are, once again, left with many gaps and silences in our narratives. What are the contingencies? The inclusive historian must identify creative methods of (re)interpretation and future preservation. Ultimately, absence is as telling as presence. What histories of sexuality get censored, based on the norms of their narrators, audiences, or the materials themselves?

For example, Sara Hodson, the Curator of Literary Manuscripts at The Huntington Library, processed the personal documents and correspondence of a gay man, containing the intimate details and confessions of their authors. In accordance with the Society of American Archivists’ Code of Ethics (“respect the privacy of people in collections, especially those who had no say in the disposition of the papers”), Hodson considered the possibility of outing anyone were the letters made publicly accessible.[vii] Similarly, we must prioritize the consent of those whose names and images appear in pornographic materials, lest they be unwillingly identified as sex workers. And what if all involved parties are unidentifiable or deceased? Is attempting to locate and contact them (or their next of kin) for permissions already a violation of their privacy?[viii] Hodson’s “decision-by-avoidance”[ix]—allowing enough time to pass to ensure that public access has, in all likelihood, become a nonissue—while practical, does not allow us to tackle the larger philosophical conundrums of our work.

How are ideas about sexuality in a given historical context evinced in these materials? Conversely, how are these sexual materials evinced in particular historical contexts? In other words, sexuality both shapes and is shaped by history and society. Consider again pornographic materials—while certainly not unique to queer collections, they tend to be more prevalent, thus jarring a placid archivist or curator into recognizing the intractability of attempting to be both inclusive of sexual minorities and keeping their repository “respectable.” Indeed, once pornography intersects with identity and community, it is difficult to accurately position the “objectivity” of the processor. How do we reexamine the role of historians in crafting erotic histories, making them “suitable” for public consumption, especially when said histories are a part of a larger narrative of liberation and representation (e.g., the increasing visibility of queer material culture)?

How is the history of sexuality sanitized for public consumption at the cost of inclusivity? For example, the Western Australian Museum came under fire in 2018 for acquiring and exhibiting a glory hole. The glory hole is part of a wooden toilet door from a demolished train station—a popular hookup spot prior to the 1990 decriminalization of sex between men. This piece of material culture was part of a historic site, where a queer counterpublic was formed. As described in the introduction of this article, sexual behavior is an external and usually private experience, but not always. When sexual behavior is public, it could be identified as hookups, sex work, or masturbation. Such taboo history is not often discussed in museum, archives, or other public history contexts. “Public” sex takes many forms, is not easily defined, and has various social, cultural, political, and legal implications. Critics were primarily concerned with audiences—children who might see the glory hole on display. Despite the lack of anything explicit in the object itself, its implications are enough to shock.

The inclusive historian seeks to interrogate stigma. However, social, cultural, political, and economic considerations may constrain this process. Do you work at a small local archive or historic site, a national institution, private or nonprofit organization? Are you a Catholic schoolteacher with students under eighteen years of age or a tenured professor at a prestigious, liberal university? The inclusive historian’s dependence on private funders, corporate sponsors, and/or public opinion ultimately informs their work. Capitalism censors and drives the narrative, as does racism, sexism, classism, and ableism (past and present). The history of sexuality shapes and is continually shaped by the power dynamics of our society. As historians, we may, unfortunately, end up as cogs in the machine, churning out the narratives most palatable to those in power.

Crafting Grassroots Narratives

When attempting to craft grassroots narratives apart from institutionalized history-making, the inclusive historian prioritizes the direct involvement of the historical “subjects” themselves (if alive) or, if not them, then members of their community. Consider the differences and similarities between your audience and your “subjects.” Whose experiences are being studied and explained—and for whom? An inclusive historian does not speak for their “subjects” or give voice to their experiences.

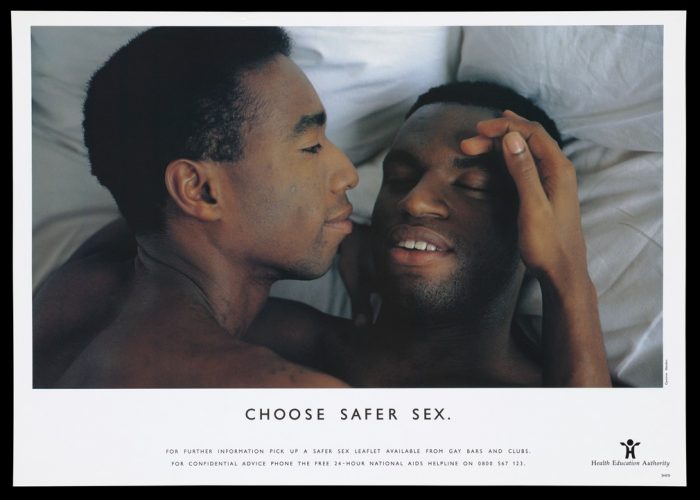

The inclusive historian is wary of discordant curation, as well as collection—for example, white scholars “specializing” in Black HIV/AIDS history being chosen to consult on an exhibition over actual Black HIV/AIDS activists whose materials and oral histories were included in said exhibition. The inclusive historian understands that equitable practice permeates all facets of historical production—collection, interpretation, and consumption. Whose materials are preserved, who fits them into a narrative, and who gets to learn about the history? Consider the (in)consistencies in demographics between these three groups. In this example, tapping into public power-knowledge—elder community leaders’ memories and legacies, as well as younger constituents’ reflections and connections to this past—would have guaranteed the practitioners involved in the project did not fall into the trap of claiming working-class, queer, and trans histories of color and history-makers of color “don’t exist” but are, rather, excluded from and within elite structures.

The inclusive historian must move beyond the notion that only “professionals” or “practitioners” can bestow historical authenticity. Even with “community-based” work, bear in mind that problems can arise. Oral history projects often appropriate people’s testimonies without compensation or involvement (such that practitioners take without giving back and are, in turn, celebrated for their “scholarship”). Similarly, “advisory groups” may invite token minorities to “sign off” on a predetermined narrative late in the planning process. But the inclusive historian values, supports, and prioritizes the knowledge and cultural production of people outside of the so-called public history field. What does the community get out of a history-making project? What does the community want from a history-making project? What rich and valuable experiences and insights can the community exchange equitably through a history-making project?

Conclusion

Interpreting the history of sexuality encompasses myriad subjects—movements and activisms; kinship and family-making; interracial relationships and mixedness; sexed people; stigmas against particular sex acts and desires; pornography and erotica; BDSM; sexology and medical institutions; eugenics, enslavement, abuse, and assault; reproductive health, STDs, and HIV/AIDS; sex work and the advent of cybersex. Once again, as an inclusive historian, it is your job to expand how these histories can be told using the resources available to you. Documentary evidence for sexuality includes how-to books, skin mags, and medical literature. The material culture of sexuality includes sex toys, film, and contraceptives. At a historic site, where does sexuality hold relevance? Was sexuality truly confined to the bedroom? Bear in mind that sexuality can be experienced anywhere, anytime. And how do we move beyond treating the history of sexuality as something “dead,” to be mediated through materials separate from their original contexts? How do we involve the living in their interpretation—the first-person narratives of historical actors themselves? Finally, with the advent of the Digital Age, we may consider how our sexualities are mediated through technology and encourage our audiences to reflect on how their sexual experiences are similar to, or different from, sexual experiences of the past. As an inclusive historian, you must continually challenge yourself (and your institution) to expand what comes to mind when you think of the history of sexuality and, in turn, what sorts of materials and stories should be included in your narrative production.

Notes

[i] LGBTQIA+ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and additional identities.

[ii] David M. Halperin, “Is There a History of Sexuality?,” History and Theory 28 (1989): 257.

[iii] In another entry on “Gender,” a co-author will elucidate the differences between sex (as in a combination of biological and anatomical characteristics unique to an individual body) and gender (a fluid combination of roles, identities, and expressions). One thing to note on how interrelated these concepts are with sexuality is that they are all social constructs. We might often hear that gender is a social construct—born of societal expectations for sexed bodies. But what we do not often discuss is how sex is also a social construct—created by modern, western medical establishments to fit bodies into categories. The dichotomous categories of male and female are each a specific combination of myriad elements—such as hormones, chromosomes, and primary/secondary sex characteristics. Each of these elements has myriad manifestations—different balances of estrogen and testosterone, other chromosomes besides XX and XY, internal and external genitalia in different forms and sizes, etc.—and they occur in different combinations. In other words, sexed bodies are infinite and diverse. In turn, an inclusive, historical approach to sexuality would examine not just how different genders (roles, identities, and expressions) have interacted sexually over time but how different sexes (different bodies and the categories placed on them) have been desired and identified, fit together, and found pleasure over time.

[iv] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (New York: Random House, 1978).

[v] Cisheterocentric comes from ciscentric and heterocentric. Ciscentric comes from cisgender—cisgender people identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (as opposed to transgender people, who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth). Heterocentric comes from heterosexual—heterosexual people are attracted to people of another sex.

[vi] Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha. Thiefing Sugar: Eroticism between Women in Caribbean Literature. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

[vii] Sara S. Hodson, “In Secret Kept, in Silence Sealed: Privacy in the Papers of Authors and Celebrities,” The American Archivist 67 (2004): 200–201.

[viii] For an example of privacy rights violation posed by the advent of new technologies, please refer to Luke O’Neil, “How Facial Recognition Software Is Changing the Porn Industry,” Esquire, September 27, 2016, http://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/sex/news/a48942/porn-facial-recognition.

[ix] Hodson, “In Secret Kept, in Silence Sealed,” 200–201.

Suggested Readings

Ferentinos, Susan.” Lifting our skirts: Sharing the sexual past with visitors.” History@Work. 1 July 2014. https://ncph.org/history-at-work/lifting-our-skirts/.

Hansen, Karen V. “‘No Kisses Is Like Youres’: An Erotic Friendship Between Two African-American Women During the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Gender and History 7 (1995): 153-182.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

Liu, Petrus. “Why Does Queer Theory Need China?.” positions 18 (2010): 291-320.

NOTCHES: a peer-reviewed, collaborative, and international history of sexuality blog. At: http://NotchesBlog.com/

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. and George Chauncey. “Thinking Sexuality Transnationally: An Introduction.” GLQ 5 (1999): 439-449.

Tang, GVGK. “Sex in the Archives: The Politics of Processing and Preserving Pornography in the Digital Age.” The American Archivist 80, no. 2 (2017): 439-452.

Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha. “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage.” GLQ 14 (2008): 191-215.

Author

~ GVGK Tang is a public historian and community organizer with a background in transnational queer politics. Tang serves on the Long-Range Planning Committee and Diversity & Inclusion Task Force for NCPH. To get in touch, visit @gvgktang on Twitter and gvgktang.com.