When public historians talk about making spaces and programs accessible, they can mean anything from affordable pricing to multi-lingual offerings to age-appropriate content. Yet in recent years, the term accessibility has most frequently come to mean ensuring access for people with disabilities. Often the focus is on elevators and restrooms, with a strong emphasis on providing facilities that serve those with physical limitations. A recent Project Access white paper entitled “Beyond Ramps” appropriately asks readers to think more broadly about barriers, although the focus remains on mobility rather than sensory or cognitive disabilities.

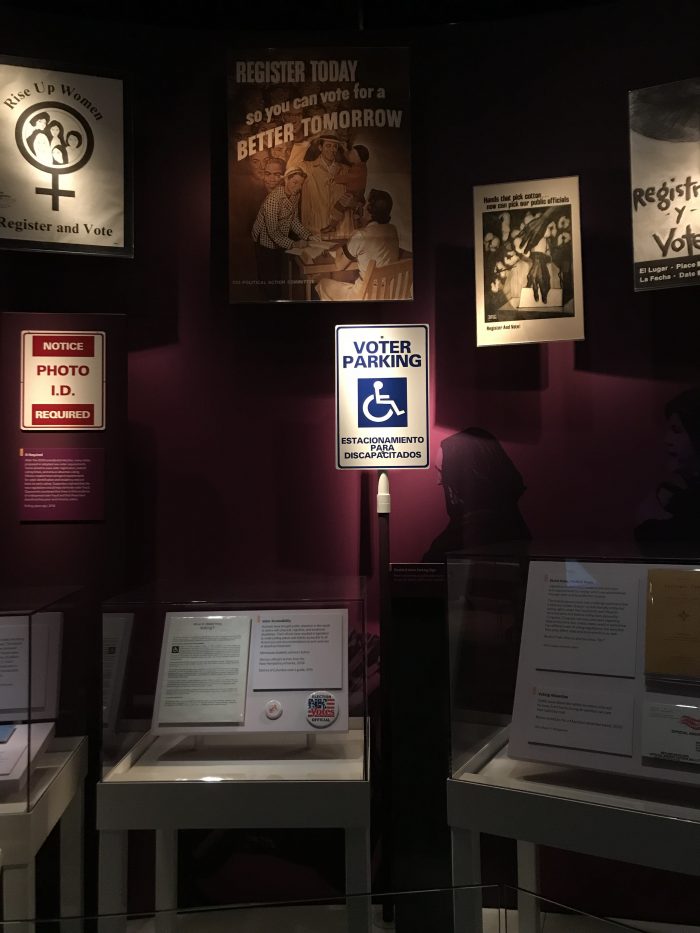

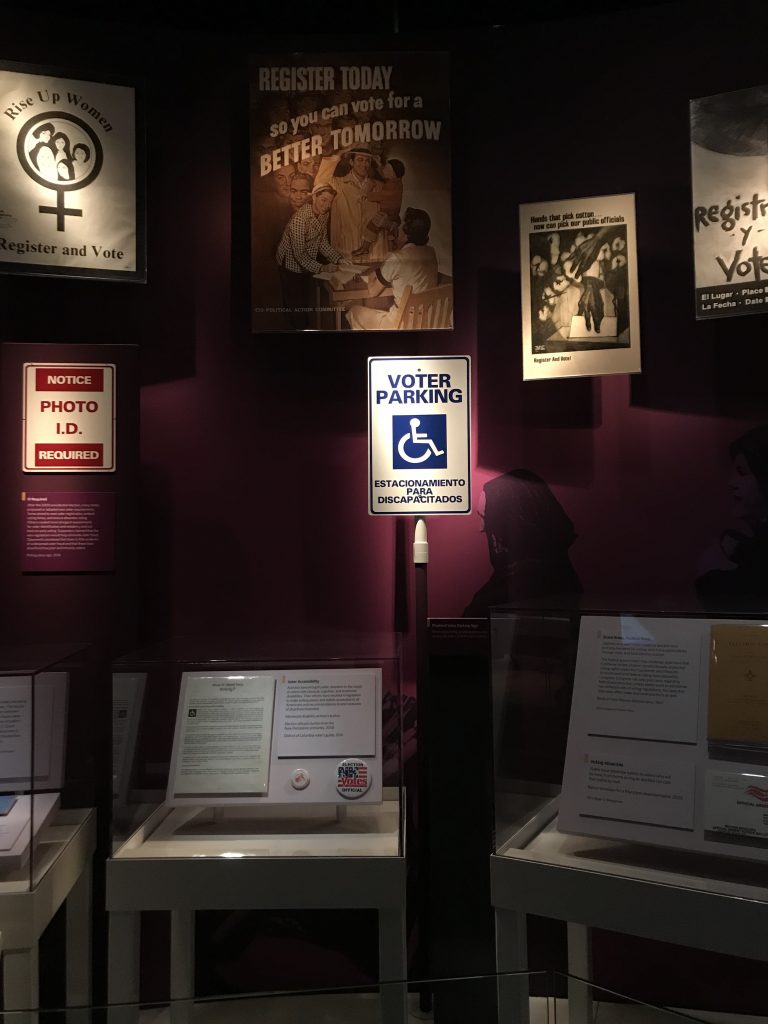

In planning for accessibility, it is important to remember that disabilities are far from uniform. In addition to mobility, physical impairments may affect sight or hearing. Cognitive abilities may be diminished by dementia. Sensory sensitivities may result from autism. Mental illness may cause anxiety or phobias that make public places difficult to navigate. The Americans with Disabilities Act (section 12102) defines a disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities,” such as walking, standing, working, learning, communicating, reading, thinking, or even breathing. Although a common symbol for accessibility is a schematic of a person in a wheelchair, the reality is that impairments are often invisible and do not have to involve recognizable assistive devices.

Most people will experience a disability at some point in their lives. In 2010, almost 19 percent of all Americans, or 56,672,000 individuals, reported a disability. As a person’s age increased, so did the likelihood of an impairment. Among those 65 years of age and older, almost 39 percent reported at least one disability, while the number jumped to more than 72 percent among those 85 and over. Add to this temporary impairments due to injuries, illnesses, or medical procedures, and it is more likely than not that anyone reading this will at some time experience a physical or cognitive limitation.

Legal Framework

In the United States, several Federal anti-discrimination laws protect people with disabilities. The Architectural Barriers Act, enacted in 1968, regulates buildings designed, constructed, or altered by the Federal government; the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 applies to federally funded programs or activities. Congress enacted more sweeping legislation in 1990 with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which applies not only to federally supported enterprises but also to other places, including those that are privately owned and operated, where public access is expected. The ADA is important civil rights legislation that establishes a minimum threshold for the inclusion of people with disabilities in American society. Among its stated goals are “equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency” (Section 12010). Failure to comply with the ADA constitutes discrimination, just as excluding people based on their skin color or national background would.

Several portions of the Americans with Disabilities Act apply to those working in the public history sector. Title I concerns employment and makes it illegal to discriminate against individuals on the basis of disability. Title II applies to public services provided by entities of state or local government, including some museums, libraries, educational institutions, and arts organizations. At the state or local level, Title II of the ADA requires that a public entity not deny “the benefits of services, programs, or activities” to individuals with disabilities (Section 12132). It is important to note that Title II emphasizes programming, so it may not be legally necessary to make all facilities physically accessible, although this should always be the goal.

Title III of the ADA applies to public accommodations and services operated by private entities, a category that includes most history organizations. Section 12182 of the law prohibits owners or operators of public accommodations from discriminating against anyone with a disability. The ADA further specifies that providing unequal benefits or separate benefits constitutes discrimination, and the law lays the groundwork for the provision of integrated spaces that serve people with disabilities as well as those who are able-bodied.

Historic Sites

The need for physically accessible facilities can present special challenges at historic sites or in historic buildings (e.g., stairs or narrow doors or passages that do not accommodate wheelchairs). The ADA includes provisions that specifically address resources listed on, or eligible for, the National Register of Historic Places, as well as those designated at the state or local level. Building owners are not required to undertake accessibility measures that threaten or destroy historic resources. Yet if the goal is to provide access to the public, refusing to address accessibility is counterproductive. Some champions of disability rights have argued that not providing access to public buildings is akin to using Confederate symbols: it harkens back to a period of widespread discrimination before universal civil rights in the United States.[1] Nevertheless, the National Park Service walks a fine line in its Preservation Brief on the topic of access, calling for “balance” between historic preservation and accessibility.

The goal at historic properties should be for all visitors, regardless of ability, to have the same positive experience. Ramped entrance to the first floor should be a minimum standard, keeping in mind that all visitors should use the same entrances. If upper or lower floors are an integral part of the experience, people who cannot use stairs will need to be provided with access through alternative means (e.g., audio-visual materials). Some sites have been able to bypass stairs with an appropriately placed elevator or lift.

Physical access is not the only way historic places should serve people with disabilities. Historic sites provide ideal environments for tactile engagement, and staff should be prepared with touchable materials, as well as verbal descriptions, for those who are blind or have low vision. As a guided tour is often the primary avenue for experiencing a historic site, printed materials should be available for those who have difficulty hearing a docent. Sites that have significant visitation, especially within confined spaces, may consider adding special hours or special programs for those on the autism spectrum and their caregivers, during which time loud noises and other disruptions are minimized. Moreover, enacting policies that welcome service and emotional support animals are critical to avoiding controversies at sites that otherwise do not allow animals.

Universal Design

Public history sites should strive to exceed the standards set in the Americans with Disabilities Act, which is now more than twenty-five years old. Simply creating or refashioning spaces and programs to meet the legislated obligations of ADA is not enough, and professionals should seek more holistic solutions that recognize the broad range of abilities among individuals. Public history organizations should make inclusive design their overall objective and create environments that serve the greatest number of people. Designers who once used a “standard” male body to determine the appropriate measurements for architectural elements, for example, need to recognize that size, strength, mobility, or sensory perception vary person to person.

Ronald Mace coined the term Universal Design in 1985 to denote “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” By offering multiple intellectual entry points and seeking aesthetic solutions that are easy to use and easy to communicate, Mace’s principles can help public historians meet audiences where they are and engage people through informal learning opportunities. Today some designers question the possibility of truly universal design[2] and are employing terms such as inclusive design or human-centered design, which recognize the range of human diversity, physical and otherwise. Still, the seven principles of Universal Design—Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Use, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Size and Space for Approach and Use—still remain good guidelines for planning.

Eliminating Barriers

In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank began the first chapter of the World Report on Disability with the statement: “Disability is part of the human condition.” The report marked an important transition in how disability is understood. Western society has long seen impairments as medical problems to be solved. This medical approach calls for treatment and, when that fails, charity, and has often led to the institutionalization of people with physical or cognitive impairments. Today, the medical model has been combined with, and increasingly replaced by, a social model of disability, which recognizes the role that environment, both physical and attitudinal, plays in how an impairment is experienced. According to the WHO, environmental factors—including products and technology, the natural and built environment, attitudes, services, systems, support networks, and policies—can be either facilitators or barriers.

Public historians have an obligation, as stewards of tangible and intangible resources for the public good, to create positive encounters for people with disabilities. For organizations such as libraries, museums, historical societies, and historic house museums, this means considering the whole experience, from pre-visit planning to transportation and wayfinding to interactions with staff or volunteers to services to ensure a comfortable visit. Some accessibility solutions are easy and relatively inexpensive: creating wide and uncluttered aisles, flexible seating for programming, and scheduled times for those who require quieter, less-crowded spaces.

Public historians should be prepared to collaborate with organizations that specialize in serving people with disabilities. It is difficult to be an expert in every aspect of accessibility, so history organizations must be willing to learn from those who live with impairments, their caregivers, and the groups that serve them. Not everyone may agree on the one best solution, but getting to know members of the local community and their preferences will allow for better access and better relationships. Regional ADA Centers are great resources as well.

Communication is key to avoiding misunderstandings and perpetuating stereotypes. Training is necessary to ensure that staff and volunteers are prepared to answer questions, advertise opportunities, and explain policies. Information about accessibility should always be conveyed in online and print publications. Marketing materials should provide contact information for those who wish to make arrangements for accommodations. Website design should follow the principles developed by the Web Accessibility Initiative. Websites can be easily audited using a free online tool such as www.webaccessibility.com to ensure that they serve users who cannot see well or do not have the dexterity to navigate the internet using a touchscreen, mouse, or similar device. Audio-visual materials used onsite or on the internet should be captioned, and the need for braille text and American Sign Language interpretation should be assessed for exhibits and programs.

Spoken and written words should always seek to humanize all visitors, and public historians should use people-first language and recognize that people with disabilities are first and foremost individuals who should not be defined by their impairments. In addition, people-first language means avoiding categorizing able-bodied people as “normal” and those with disabilities as “handicapped.”

Just as language is important, so is the content public historians offer to their audiences. When representing the human form in signage and exhibits, consider including people who use assistive devices such as canes, wheelchairs, or scooters. When developing exhibition or program topics, explore the history of disability; there are often compelling stories to tell, and lessons to be learned, about local institutions such as hospitals, schools, and mental health facilities, as well as the experiences of soldiers returning from conflict zones with war-related injuries and psychological trauma. Many historical societies have collections that include artifacts related to the ways in which people with physical or cognitive disabilities have become more independent or found creative outlets, and public historians should make better use of these collections.

Accessibility is fundamentally about empowerment. For too long society has marginalized those with disabilities. We can reverse that trend by providing accessible spaces and activities, communicating clearly what we offer and where we need help, and bringing the topic of disability from the sidelines to the center. We should be advocates for and models of inclusive design, people-first language, and recognizing the centrality of physical and cognitive limitations to the human experience. Too often people argue that accessibility is not necessary or important because people with impairments do not visit and costs are too high to make it worthwhile. The reality is that we, as public historians, have to convey to those with disabilities that we have something to offer and we are willing to invest in making sure every experience is complete and meaningful.

Notes

[1] Wanda Liebermann, “Architectural Heritage, Disabled Access, and the Memory Landscape,” paper presented at the Society of Architectural Historians annual meeting, St. Paul, Minnesota, April 20, 2018.

[2] Bess Williamson, “Getting a Grip: Disability in American Industrial Design of the Late Twentieth Century,” Winterthur Portfolio 46, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 232-234.

Suggested Readings

Art Beyond Sight. Museum Education Institute. http://www.artbeyondsight.org/mei/.

Clary, Katie Stringer. Programming for People with Special Needs: A Guide for Museums and Historic Sites. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield/AASLH, 2014.

Ginley, Barry. “Museums: A Whole New World for Visually Impaired People.” Disability Studies Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2013). http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3761/3276.

Hamraie, Aimi. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Jester, Thomas C. and Sharon C. Park, “Making Historic Properties Accessible.” Preservation Briefs 32. https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/preservedocs/preservation-briefs/32Preserve-Brief-Accessible.pdf.

Kudick, Catherine. “The Local History Museum, So Near and Yet So Far.” The Public Historian 27, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 75-81.

Museum Access Consortium. “Working Document of Best Practices: Tips for Making All Visitors Feel Welcome.” 2015. https://macaccess.org/rescources/working-document-of-best-practices-tips-for-making-all-visitors-feel-welcome/.

Smithsonian Accessibility Program. “Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design.” https://www.si.edu/Accessibility/SGAED.

Author

~ Cynthia G. Falk is Professor at the Cooperstown Graduate Program, a master’s degree program in museum studies at the State University of New York College at Oneonta. Falk is the author of the books Barns of New York: Rural Architecture of the Empire State and Architecture and Artifacts of the Pennsylvania Germans: Constructing Identity in Early America. She served as the co-editor of Buildings & Landscapes, the journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, from 2012 to 2017 and is currently Deputy Mayor of the Village of Cooperstown. Falk can be reached by email at [email protected].

Download a PDF of this entry: Accessibility_Falk_The-Inclusive-Historians-Handbook.