The work that historians do is pivotal to the success of an inclusive civics education centered on debate, perspective taking, civil discourse, and knowledge of the rule of law. Sharing how evidence is gathered and analyzed to make arguments about the past prepares students for civic work in which they are asked why they think the way they do, instead of being told what to think. These skills are not merely important in a classroom setting but are lifelong skills students take into the real world when determining bias in media, understanding viewpoints different from their own, and contributing to civil discourse and compromise.

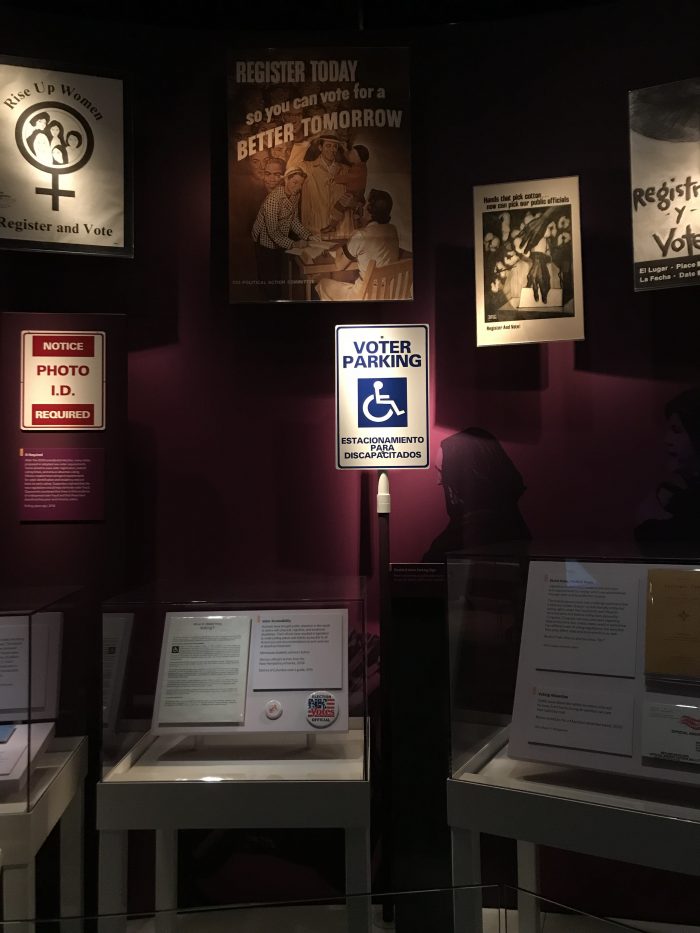

Current trends in civics instruction and curricula go beyond teaching students about the structure of participatory government. While understanding the rule of law at the national, state, and local levels is critical for young people to contribute to democracy, it is also essential for educational institutions to teach civic dispositions, such as an appreciation and understanding of free speech and willingness to engage with those whose perspectives are different from their own. Classrooms, museums, historic sites, and other educational spaces provide opportunities to practice and develop these skills and build confidence in civic behaviors, such as voting, volunteering, and voicing informed opinions at public meetings.[i]

Elevating historical examples that connect the past with the present—examples that link to issues students encounter in their daily lives—can have profound resonance and empower meaningful engagement.[ii]

Historical Background

Instructing Americans on the “principles of virtue and of liberty; and inspir[ing] them with just and liberal ideas of government”[iii] was a key issue in the public discourse of the eighteenth century around the creation of a new national identity distinct from the rest of the world. Ensuring the nation’s civic life beyond the generation that formed the new government hinged on informed civic participation for those deemed eligible to participate in the process. Leading education philosophers—including Noah Webster in the 1700s, Horace Mann in the 1800s, and John and Evelyn Dewey in the 1900s—contributed to the educational foundation of civics knowledge and its practical application to activate citizens for a participatory democracy.

The work continues today; and in order to ensure all students are prepared to be full participants in a democracy, civics must be taught through an inclusive lens in contemporary classrooms and other educational spaces. This approach resonates with a younger generation whose learning landscape has been defined by heightened participatory experiences throughout their lives. The alternative approach, which prioritizes only civic knowledge without civic dispositions, limits students’ voices and hinders preparedness for civic life. The development of the skills needed to engage in political discourse and contribute to society in meaningful and productive ways are more critical than ever before within a “universe of unregulated information at our fingertips.”[iv]

The Role of History in the Civics Classroom

Civics teachers value the joy that comes from their students making connections with the broader world, a world in which they are able to advocate to support or change existing policies. This objective can be achieved through lessons grounded in historical context and sources. When done right, teaching civics is difficult; the challenge of this work starts with harnessing student interest and focus. Some want to move directly to action without the historical context to inform their perspectives; while others bring indifference and need to be inspired to be participatory actors in their communities. This work is even harder when a community is held hostage by partisanship that deters teachers from creating healthy discussions around civics topics.

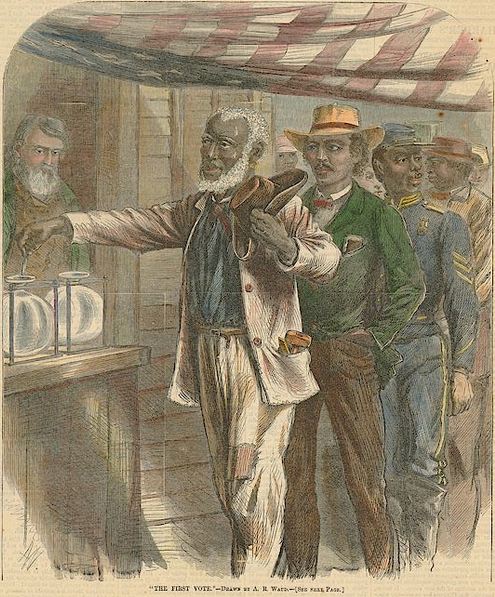

Teaching civics through the arc of U.S. history provides students untold examples of debates large and small, which show dialogue and discussion by everyday actors in real-life situations and shape the world in which we now operate. Historical content and sources make visible the bumps, cracks, and turns in what can be otherwise disguised as a smooth road and which may wrongly suggest a simple progressive narrative of political history. Historians activate the work of people in the past and help combat the perception that individuals are passive recipients of legislation, laws, and policies. This work can also make visible the individuals and groups that were excluded from civic participation and the world made by the marginalization of their voices. Using historical case studies provides the connection between the ideals of the more perfect union and how those ideals (through policies and institutions) have been created and sustained.[v] This gives the impassioned students historical context through which to align or challenge their thinking. It also can empower the apathetic students who can study a place and time when someone with whom they identify had a voice that impacted history. Allowing students access to the sources, context, and the thinking process of this type of research builds on their capacity to see, contribute, and transform policies and institutions today and in the future.

Practicing historical thinking skills allows for civics classrooms to explore historical debates from multiple perspectives—with a critical eye on sourcing—while benefiting from the time-telescoped view of the context in which these debates occurred. Having students study the past through historical sources and events also provides valuable tools to see the continuity and changes between then and now. For each level of government—whether local, state, or national, or more importantly, the interplay between them in a federalist system—the challenges and limitations built into the infrastructure can be made visible by looking at them over time. In a world where social media democratizes and polarizes information sharing, students armed with these skills are better prepared to analyze, discern, and contribute to political dialogues and decision-making that shapes their lives.

Providing Historical Examples

Historians provide the rich historical narrative upon which civic instruction is built. Inclusive civics educators value contributions from historians and historical institutions that provide vetted sources, historical context, and voices on multiple sides of the debates or issues illustrated. Ideal primary source sets suited for civics classroom adoption should illustrate the successes of constructive government as well as visible failures to achieve compromise or enact positive legislation. Dedicated civics instructors sometimes find themselves (late at night) scouring the internet and doing the vetting to create a document set that shows more than one perspective for their students. Being able to work from research that historians have already done—and that is positioned to support civics lessons in dialogue with current events—creates a richer and more scholarly-sound learning environment.

Examples of this type of teaching resource are offered on a number of history and archival sites, including the website of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP). Using the sources from their collection and the expertise they bring in interpreting them, HSP has provided ideal building blocks for educators and students. The primary sources illustrate different perspectives organized by topic and are supported by historical context, essential questions, and background material. Their unit “Economics through the Long History of America’s First Bank,” designed for an economics or history classroom, can be transferred to a civics classroom because it explores the relationship between capitalism and government. Going beyond the high standard of providing vetted source sets digitally, HSP also provides transparency regarding the author and the funder of the curriculum. As a result, the perspective of the institution that selected the sources and framed the questions is also open for student analysis.

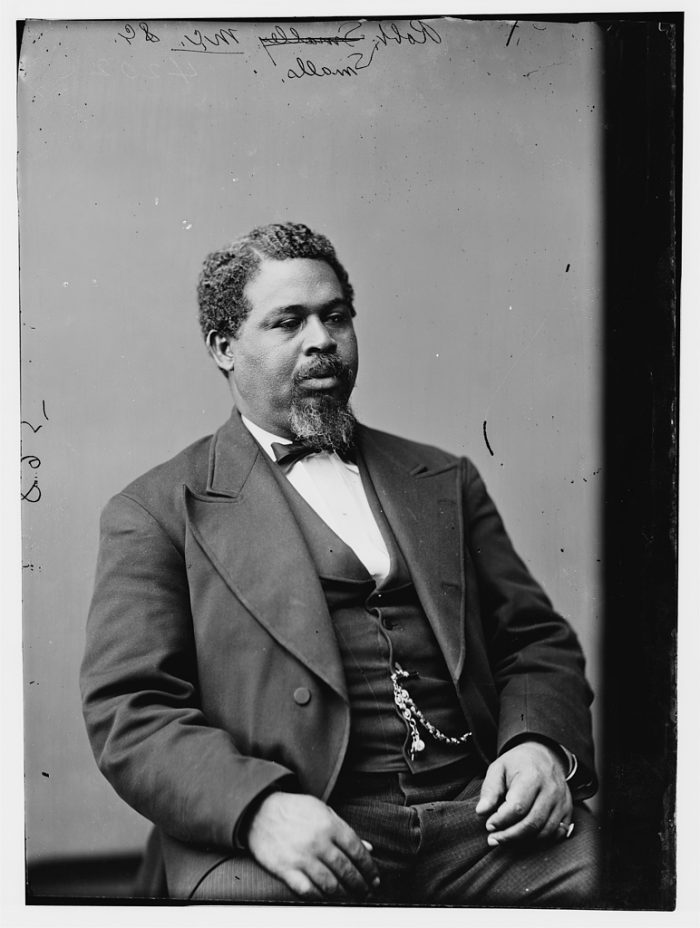

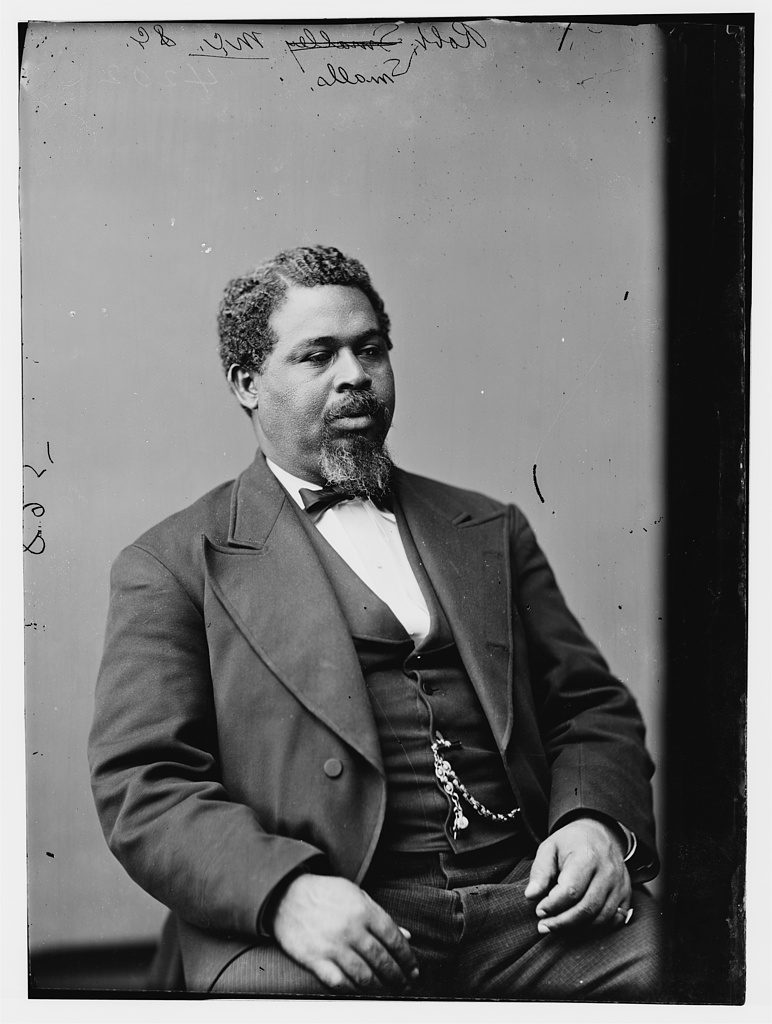

Another example that reflects a more focused scope is the Colored Conventions Project, which provides documentary records and expert-curated document collections related to a series of civic meetings held in Black communities between 1830 and 1890 in the United States and Canada. The variety of sources and the historical inquiry approach model how students can see civic engagement in diverse ways. Newspaper archives combined with data visualizations sit alongside expert interpretation and inquiry prompts. Although men are most prominent in the newspaper accounts of these events, the site also brings to light the civic work women did in these communities to ensure the success of the conventions. The site includes named scholars who can speak further about the project so students have deeper access to experts beyond what is authored on the site.

Resources for Young Civics Learners

Learning about our nation’s history and government also means learning about the history of race in the United States. While integral to all civics coursework, race-based slavery and its continued legacy should be a part of young learners’ knowledge of how our past informs the present. The history of race is too often left out of elementary classrooms or limited to instruction about the achievements of leading figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harriet Tubman. Teaching students in these grades about all who participated in history is foundational; leaving out a group is the equivalent of excising part of the American story. Children’s historical literature, with context provided by historians and paired with primary sources, gives educators multiple platforms for young learners to have guided and foundational conversations about race and their world.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture provides a series of collections stories that bring context, quotes, and historic artifacts and documents together. Lives in Pieces addresses the four young Black girls killed at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963. The central object in the collection are shards of broken stained glass from the church window. Paired with We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Levinson (non-fiction) and The Watsons Go to Birmingham-1963 by Christopher Paul Curtis (fiction), these objects can provide essential civics instruction through historical inquiry and sources.

At the elementary level, civics is intertwined with community lessons, U.S. history lessons, and classroom social and emotional learning standards. Ensuring that historical sources and research can be connected to civics for younger students will prepare them for more complex debates and arguments later in their scholastic study. The National Constitution Center partnered with the Rendell Center for Citizenship and Civics at Arcadia University to create eight elementary lessons that connect fourth-grade state-based civics instruction to student-led classroom responsibilities. We the Civics Kids includes a young readers civics literature list, organized by month to align with state and national holidays and commemorations. Each lesson provides historical context for civics topics that elementary students confront in their classrooms today.

Local History’s Value to Civics Education

For students, discussions about government policies and structures at the national level may sometimes seem most pressing, but in reality, most state civics standards focus as much, if not more, on the unique features of state and local governments. Student engagement with state and local policies creates a more immediate impact on, and connection to, their communities. Historical research often provides a detailed look at a specific time and place, and the work historians do to illustrate the voices engaged in local governance and debate can translate powerfully to a classroom in the same community or state. Seeing the workings of government in which the local community has a more direct impact can inspire student participation in the civics process.

From 2009 to 2018 the Minnesota Department of Education and seven other state-wide organizations worked together on the Minnesota Center for Social Studies Education (CSSE). Focusing on a state-wide approach to social studies education enabled civics instructional materials to apply directly to state standards and the unique challenges facing students in preparing to contribute to their own governance. The sources and interpretation for the exhibition Why Treaties Matter: Self-Government in the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations, created by the Minnesota Humanities Center and Minnesota Indian Affairs Council, directly address the state’s high school civics standard: “Explain how tribal sovereignty establishes a unique relationship between American Indian Nations and the United States Government.” One of the educator guides takes a question framed about the U.S. federal government and tribal nations and localizes the content for the state in which the students live.

The fact that state learning standards include state history and government in their social studies curricula provides a great opportunity to pair civics learning and history learning with a regional focus. Indiana University’s Center on Representative Government, for example, provides a state-based civics instruction tool for Indiana high school students entitled CitizIN.

Local history resources can also connect the civics of the students’ own communities with national stories covered in their history curriculum. The Tsongas Industrial History Center connects local students to the broader story of the Industrial Revolution through the Lowell Mills in nineteenth-century Massachusetts. They use digitized primary sources to show all the components of the Industrial Revolution in a local community thereby connecting individual lives to larger historical themes.

Activating People who Lived in the Past through Games

For some students, a lack of interest in history and historical actors can be attributed to the passive nature in which those people who lived in the past are often portrayed. Historical contributions to civics education can be as simple as providing narratives and sources that demonstrate people in the past had an impact on the world in which they lived. The past is filled with people who are not given the agency in traditional textbooks that they possessed in life. A powerful way to shift this is through interactive games.

The interactive Be Washington Experience, created by George Washington’s Mount Vernon, activates George Washington’s role in history and provides the context and perspectives of others who shaped his decisions. Although a powerfully influential decision-maker in his time, students can still speak of his contributions in a passive way, “he was president” being the most common paraphrase of his contributions. The game asks students to make a decision Washington had to make, but before they do, they listen to eight other people and perspectives from the time. Sources Washington would have had access to inform students on different perspectives relating to the controversies like the Whiskey Rebellion that pitted federal tax policy against states’ interests early in U.S. history. After making their choices, student answers are put in dialogue with the historical record and they can compare and contrast their perspective on the issue and how it differed or aligned with Washington’s. Applied in a civics context, the topic of states’ rights and federal authority that Washington wrestled with can be connected to the same debates happening at the national level today.[vi]

The game site iCivics is known for its immersive and addictive games that teach government and the rule of law. In 2019 they launched their first historical game, designed to illustrate the origins of our governing documents. Race to Ratify sets players up to decide if they support or oppose the ratification of the U.S. Constitution while taking a position of a federalist (advocating for the Constitution) or anti-federalist (advocating against the Constitution, or the Constitution adopted with the Bill of Rights). They meet with diverse individuals from all 13 states. Their work is to understand the perspectives and interests of others and make arguments to persuade others of their opinions. What was once a lesson framed by faceless “states” approving foundational documents becomes a way to see the eighteenth century as one filled with diverse people who held differing and dynamic views. The game-based and personality-driven platform gives students a chance to not only learn about these historic events, but also practice the skills needed for participatory government.

Historical Thinking Skills = Media Literacy Skills

DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with primary sources from the National Archives and Records Administration, illustrates how effectively moving beyond simply providing digital collections online impacts the effectiveness of applying those sources to civics instruction. With thousands of documents carefully selected for the platform, teachers use built-in tools to ensure that students do not merely learn from the sources but use those sources in improving their ability to apply their own analysis to larger ideas. The digital tools parallel the media literacy skills students need to participate effectively in, and advocate for, their ideas in public dialogue today. The site supports teachers in creating document sets that help students make connections, contextualize both time and place, weigh evidence based on validity and perspective, and interpret data to make meaning from statistics.

Stanford University created the Reading Like a Historian curriculum to support teachers in integrating historical thinking skills into their classrooms. As research has shown the positive impact of this type of teaching, they recently expanded their contributions to include the “Civic Online Reasoning” curriculum. Finally, Engaging Congress is a strong interactive tool that combines gaming elements with historic primary sources to develop media literacy skills. It uses inquiry and drag-and-drop tools laid over source materials to teach the basic structures of government and the challenges they bring in the world today.

History Provides Students with the Knowledge and Tools for Civic Participation

Civics is sometimes the first class students take in school where they learn that their opinions matter and they have a voice that will contribute to the world we all live in. The unique skills and talents that historical thinking develops play a critical role in sharpening students’ respect for others’ perspectives and the ability to articulate their own.[vii] By providing sources, contextualization, and viewpoints from a wide array of actors in history, historians contribute to a more inclusive civics classroom education. When history and civics are intertwined, students are better prepared for participation in government and have the skills to contribute to and shape institutions.

Notes

[i] Rebecca Winthrop, “The Need for Civic Education in 21st-Century Schools,” Brookings (Brookings, June 4, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/bigideas/the-need-for-civic-education-in-21st-century-schools/.

[ii] Comments ascribed to “teachers” and “classrooms” in this article are based on interviews with nine civics teachers teaching in FL, GA, MD, MO, OH, NY, KY, and PA. Interviews were conducted by the author over phone and email.

[iii] Noah Webster, “On the Necessity of Fostering American Identity after Independence, 1783 & 1787, excerpts,” National Humanities Center (NHC, 2010/2013) https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/independence/text3/websteramericanidentity.pdf.

[iv] Samuel S. Wineburg, Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone) (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018), 8.

[v] Stephen Sawchuk, “A ‘Roadmap’ for Teaching Civics and History Is Coming. Will It Restart an Old Curriculum War?,” Education Week, November 8, 2019, https://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/teaching_now/2019/11/roadmap_history_civics_neh_ed.html.

[vi] Kathleen Munn and K. Allison Wickens, “Public History Institutions: Leaders in Civics Through the Power of the Past,” Journal of Museum Education 43, no. 2 (March 2018): 91-103, https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2018.1453598.

[vii] Wineburg, 100.

Suggested Readings

Gould, Jonathan, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Peter Levine, Ted McConnell, and David B. Smith, eds. Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools. The Leonore Annenberg Institute for Civics of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, 2011. PDF available for download.

Levinson, Meira. No Citizen Left Behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

National Council for the Social Studies. The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography and History. Silver Spring, MD: National Council for the Social Studies, 2013. Revised PDF version (2017) available for download.

Nokes, Jeffery D. Teaching History, Learning Citizenship: Tools for Civic Engagement. New York: Teachers College Press, 2019.

Pennay, Anthony. The Civic Mission of Museums. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020.

Wineburg, Samuel S. Why Learn History (When it’s Already on Your Phone). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Non-partisan and non-profit organizations that collect and share history and civics resources for communities and schools:

- Civics Renewal Network aggregates classroom resources for classroom civics instruction: https://www.civicsrenewalnetwork.org/

- History Relevance provides tools to connect the events of the past with current events: https://www.historyrelevance.com/

- History Made By Us seeks to connect millennials and Gen Z with historic perspectives to better serve the ongoing conversation about the future: https://historymadebyus.com/

Author

–K Allison Wickens is the Vice President for Education at George Washington’s Mount Vernon.